Monthly Journal

May 2023

International Press Review

The most relevant events of the area through international sources

US-Kosovo relations significantly deteriorated after riots in the north

Balkan Insight

Kosovo’s relationship with the United States has deteriorated as a result of violent unrest in the country’s Serb-majority north (see The Key Story below). The United States has threatened sanctions unless Kosovo takes steps to de-escalate the situation. The first sanction, according to US Ambassador to Pristina Jeffrey Hovenier, would be the cancellation of the Kosovo Security Force’s participation in the US-led Defender Europe 2023 military exercise. Furthermore, the US will cease assisting Kosovo in gaining recognition from states that have not recognised Kosovo, as well as in the process of integration into international organisations. This is a significant setback in Kosovo’s relations with its key ally, the United States.

April’s election in Kosovo was “no solution” for the north

German Foreign Ministry

The United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, and the United States issued a joint statement on the tense situation in Kosovo. The Quint acknowledged the recent elections in Kosovo’s north, but expressed concern about the Serb community’s boycott, claiming that the election’s results do not provide a long-term political solution for the municipalities in the north of Kosovo. They urged all parts to work together to find as soon as possible a solution that ensures conditions for the long-term participatory representative democracy, while avoiding escalating tensions.

Belgrade’s leader evokes possibility of early elections

Bloomberg

In response to opposition rallies following two mass shootings that shocked the Balkan country (19 dead in total), Serbia’s President Aleksandar Vucic announced that a snap general election could be held by September. Vucic’s centre-right Progressive Party currently controls both the Parliament and the government. The most recent general elections were held in April 2022, and Vucic has previously stated that a government reshuffle in 2024 is possible. A former ultranationalist who rebranded himself as a moderate and progressive leader, the current Serbian President has been in power for more than a decade, either as prime minister or chief of State.

Violence, propaganda and hate speech in focus after mass shootings in Serbia

The Guardian

In a deeply divided nation where war criminals are still glorified, reality shows feature convicted murderers and the memories of past conflicts remain vivid, many doubt whether President Aleksandar Vucic commitment to “disarm” the country after two mass shootings in May will be sufficient, The Guardian wrote in May. During the first week of a governmental amnesty programme following recent mass shootings in Serbia, tens of thousands of weapons were surrendered by Serbian citizens. The recent shootings resulted in 19 deaths and prompted concerns about the excessive violence and its underlying causes in the Serbian society. While some support the government’s measures, others question the president’s role in fostering a culture of violence and exploitation for political purposes.

Nationalist Bosnian Serb leader meets Putin again

Reuters

Russian President Vladimir Putin met with Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik in Moscow, for the third time in 12 months. They discussed expanding trade and maintaining strong bilateral relations. Putin mentioned a 57% increase in trade between Russia and Republika Srpska and expressed hope for even better results this year. Dodik has been a vocal supporter of Russia’s actions in Ukraine, and Putin thanked him for his stance on the conflict. The meeting could harm Bosnia and Herzegovina’s EU accession ambitions, as Brussels has warned EU allies not to visit Russia. Aleksandar Vulin, the head of Serbia’s security services, also visited Moscow in May.

US bombers fly over BiH amidst new political instability

Air Force Times

Two US Air Force B-1B Lancer bombers flew over several Bosnian cities in a show of support amid secessionist threats and recurrent political crises in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In Tuzla, the bombers also took part in a joint military exercise with Bosnia’s Army and US Army Special Forces. According to US Ambassador Michael Murphy, the flights were intended to demonstrate a strong commitment to Bosnia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. Dodik, the president of Republika Srpska, has advocated for Bosnia’s dissolution and has expressed support for Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Germany reassures that Balkan countries will be part of the EU

N1

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz spoke in the European Parliament about the importance of a future-oriented, expanded, and reformed European Union with a geopolitical focus. In this scenario, Scholz emphasised the importance of the EU’s decision to grant candidate status and begin accession talks with a number of countries, including Western Balkan countries, Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia. Scholz stressed that this commitment is motivated not only by generosity, but also by economic interests. He also underlined the importance of securing peace in Europe, especially in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Balkan politicians and leaders endorse Erdogan

Daily Sabah

Prominent Balkan politicians have praised and supported Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, including Bakir Izetbegovic of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Democratic Action Party, Afrim Gashi of North Macedonian Alternative Party, Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik, and Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama. They urged Turkish voters to support Erdogan in the elections, citing alleged achievements and progress made under Erdogan’s leadership. The politicians emphasised Türkiye’s positive impact on the Balkan region.

Bosnian top diplomat warns that Russian influence is increasing

The Washington Post

Zlatko Lagumdzija, the new Bosnia and Herzegovina’s ambassador to the UN, warned that Russian President Vladimir Putin is actively intervening in the Balkans to instigate a new conflict as a distraction from the war in Ukraine. Lagumdzija urged the US to pay closer attention to the situation, emphasising that Russia’s aggression against Ukraine presents an opportunity for the West to reclaim regional influence lost to Russia and other external actors.

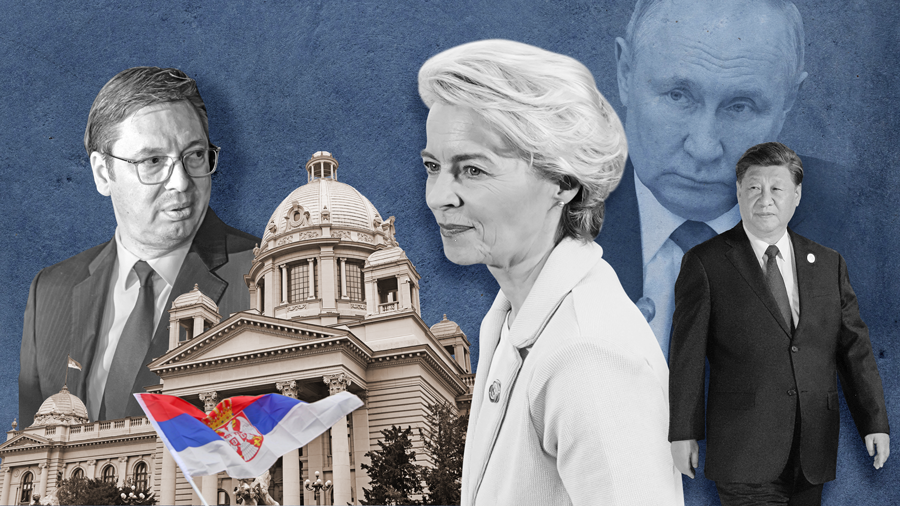

Russia, China and Turkey fighting for influence in the Balkans

Handelsblatt

The influential German daily Handelsblatt examined foreign influences in the Balkans this month, noting that Russia, China, and Turkey, along with the European Union, are competing for influence in the Western Balkans. The daily emphasized Russia’s desire to keep the region out of the EU and prevent NATO expansion, in particular in Serbia, where a huge majority of the populations see Moscow as a true ally. Türkiye was described as a patron of Balkan Muslims, while China as a power focussing on strategic moves along its Silk Road initiative. Russia primarily uses propaganda and energy policy to wield power.

Tensions rise again in Bulgaria as two parties try to form government

Euractiv

Bulgarian President Rumen Radev has asked the coalition “We Continue the Change – Democratic Bulgaria” to form a government. However, following the mandate handover ceremony, Radev refused to shake hands with the coalition’s prime minister candidate Nikolay Denkov and advised him not to carry out the task because his mandate was “already discredited.” This happens amid a scandal involving leaked recordings of the coalition’s leadership discussing the replacement of Radev-appointed heads of special services suspected of being influenced by Russia. Bulgarians went to the polls in April for the fifth time in two years.

The Insight Angle

Bodo Weber

Senior Associate at the Democratization Policy Council with a significant expertise on the Western Balkans, German and European foreign and security policy, transatlantic relations, Ukraine, and Türkiye. Weber cooperated as a political consultant for political foundations and international organizations in Germany and the Balkans. He has published numerous articles and analytical papers on EU and US policies towards the Balkans and frequently appears in regional and international media.

How can we expect the situation to develop with regards to the implementation of the European plan for the normalization of relations between Serbia and Kosovo, given that Serbian President Vucic and Kosovo’s PM Kurti have both agreed to it, but the process is slower and more challenging than expected?

I was sceptical from the very beginning that the European plan and the implementation annex agreed in Ohrid this year would lead to any swift implementation. In fact, I expected, and I still do, that the entire plan will collapse during the so-called implementation. The main reason is that, on top of the weakness of the basic agreement, the implementation annex is devoid of the substantiative elements it had originally been announced to contain: a detailed sequencing with detailed timelines for implementing the various parts of the agreement. In addition, the issue of how to return Serbs in the north of Kosovo to state institutions has not only not been solved within the agreement framework, but has not even been touched by the EU negotiators. Thus, it is, unfortunately, no surprise that ‘implementation’ got stalled over the most contentious issue – the establishment of the so-called Association of Serb-majority municipalities (ASM) – as no procedure was agreed in Ohrid on how to get to an agreement over a statute for the ASM. It is also no surprise that the issue of Serbs not being represented in Kosovo institutions since Ohrid has led to further, dramatic escalation in the north, with local elections being boycotted by Serbs, and the ethnic clashes triggered by the attempts of the ethnic Albanian elected mayors of taking office.

Do you believe that the European plan is the appropriate solution for ultimately resolving the issue of Serbia-Kosovo relations, or do you think that Brussels and Washington may have been overly optimistic in their expectations?

No, I believe that the approach taken, that is moving away from the previous framework of negotiations on a final, comprehensive agreement, to some sort of vaguely defined intermediate agreement was and is the wrong approach for several reasons. First, because it leaves most of the carrots and guarantees offered to Pristina in the form of oral promises that have failed to convince the Kosovo government. Second, it offers no solution to the issue of Kosovo Serbs. Third, an interim agreement without a long-term strategy and masterplan will ultimately fail in the long run. Finally, the plan is based on courting an autocratic regime in Belgrade and on working around Vucic’s declared red lines, when earlier dialogue phases have proven that it can only be successful when it is the West defining the principles, red lines and aim of the dialogue, making use of its full leverage over Serbia (no border changes, recognition of Kosovo in return for EU membership perspective). Thus, I believe the only real solution lies in returning to direct negotiations on a final, comprehensive agreement with Serbian recognition of Kosovo at its core, based on clear messages and strong pressure on Serbia, i.e., a strategic U-turn on the West’s policy towards Serbia.

Regarding the pace of the enlargement process in the Balkans, what is your assessment, especially considering that Bosnia and Herzegovina is experiencing cyclical crises mostly due to the secessionist policies of the Bosnian Serb leadership, as well as the lack of progress made by Montenegro, Albania, and North Macedonia towards their EU goals? How dangerous is it to proceed too slowly with the enlargement?

The problem has never been one of speed, but of the credibility of the EU’s enlargement process. This is primarily referring to maintaining a realistic offer of EU membership alive. This offer has been already undermined by the so-called ‘enlargement fatigue’ that kicked in after the 2009 Euro crisis, a dynamic that dramatically accelerated with Brexit and then with French president Macron entering office and taking an anti-enlargement stance, blocking North Macedonia’s and Albania’s opening of accession negotiations despite all conditions being fulfilled for four years. In addition, the EU, despite the long learning processes, never nurtured the enlargement process as a strategic approach and instrument for external promotion of democratic transformation and for achieving sustainable solutions for ethnic disputes and conflicts in the Western Balkans. All this has contributed to major rollback on democracy and rule of law throughout the region over the last decade.

Despite the delays in the EU integration process that started in Thessaloniki 20 years ago, do you think that EU integration is still a goal for the leaderships in the Balkans? And is it still a ‘dream’ for citizens in the region?

Most of the ruling leaders and elites in the region never genuinely wanted EU integration, as they were, and are satisfied with the corrupt, authoritarian nature of the political systems in their country, and with instrumentalizing ethnopolitical disputes and tension for such purposes. It was always primarily citizens of the region that by large majorities truly aimed at EU integration. Unfortunately, due to the weak and non-strategic approach of the EU, ruling leaders and elites have managed to easily adopt the narrative of EU integration, to present themselves as ‘champions of EU integration’, and even be praised as such by EU officials, while such de facto allyship with authoritarian elites and autocrats has increasingly alienated citizens.

If the conflict in Ukraine lasts longer than expected, should we be concerned about Russia playing a more and more destabilizing role in the Balkans? Additionally, what direct and indirect negative consequences could the conflict have on a region that is still outside of the EU, apart from Moscow’s involvement?

We should have been concerned about Russia’s increasing meddling into the region since its gradual return to the Western Balkans for over a decade, but which was for a very long time ignored by the EU, and the US. The Ukraine conflict provides dangers and opportunities. There is the risk Russia will at some point open a second front in the Balkans, making use of existing tensions in the context of unresolved status issues. On the other hand, the Ukraine war presents a window of opportunity in terms of finally kicking Russia out of the region. Thus, with the Russian aggression against Ukraine, Serbia has for the first time seriously come under pressure to end its ‘sitting between two chairs’ policy and to get rid of its energy dependency on Russia. But the West and the EU so far have missed to make use of that opportunity. EU has missed to pressure Serbia into turning away from Russia. And it has not extended the move it made when extraordinarily granting candidate status to Ukraine to the Western Balkans. Thus, as for the last decade, Russia’s leverage in the Western Balkans is primarily based on the power vacuum created by the EU, and by wider West’s weakness, not by Moscow’s strength and objective leverage.

The Key Story

Strategic trends

Serbia and Kosovo experience destabilization due to mass shootings, protests and contentious elections

Serbia and Kosovo both entered a phase of intensive internal destabilisation in May, for different reasons. The current situation suggests that the two Balkan countries, Serbia in particular, may be entering a new phase of crisis with unforeseeable negative consequences, while Kosovo is risking to be isolated even by the closest allies.

Serbia was shaken by two violent crimes, the most violent in its recent history, at the beginning of May. On the 3rd of May, a 13-year-old boy opened fire in his elementary school in down-town of Belgrade, killing nine classmates and the school guardian. Two days after, another young man killed nine people with an automatic rifle in two villages near city of Mladenovac. Protests erupted in Belgrade and other cities in response to these violent acts, with tens of thousands of people taking to the streets to condemn gun violence and the government’s policies over the last decade.

Demonstrators and opposition parties, in particular, claimed that President Aleksandar Vucic and the Serbian government contributed to a climate of intolerance and violence by using pro-government media to silence critics and opposition. The protests began peacefully but quickly became problematic for those in power, with demonstrators twice blocking a highway bridge and gathering in front of the headquarters of Serbia’s public broadcaster RTS. The pro-European opposition blamed President Aleksandar Vucic and his party for the shootings, and the protests became quickly politicised. They demanded the resignations of President Vucic, Interior Minister Bratislav Gasic and the director of Serbia’s Security Intelligence Agency (BIA), the pro-Russia Aleksandar Vulin, as well as greater media freedoms.

After Belgrade witnessed in May the largest anti-government demonstrations since the fall of Slobodan Milosevic in 2000, Vucic responded by organising a mass counter-demonstration, rallying tens of thousands of supporters in the capital, many of whom had been, as usual, bussed in from the countryside. In addition, he resigned as President of the Progressive Party, anticipating the formation of a new political movement. However, the protesters appeared unconcerned by the authorities’ response and promised to continue rallying until a regime change occurred, implying that Serbia may be entering one of the most volatile periods in the last decade. Despite Vucic’s show of strength and support, the protests are likely to continue into June, with a serious impact on the political scene.

Meanwhile, due to the contentious administrative elections held in the north of Kosovo on the 23rd of April, a new front opened at the end of May also in Kosovo. The main Kosovo Serb party, the Serbian List, boycotted the elections, and the turnout was only 3,47 percent. The Serb List called for a boycott of the elections because Belgrade’s key demands, including the formation of the Association of Serbian Municipalities (ASM) and the withdrawal of Kosovo’s special forces from the country’s north, had not been met. The results showed that Kosovo Prime Minister Albin Kurti’s Vetevendosje (Self-Determination) party won the mayoral races in North Mitrovica and Leposavic, while the opposition Democratic Party of Kosovo won in Zvecan and Zubin Potok. The low turnout immediately raised questions about the legitimacy of the election results, as well as the impact on future relations between Belgrade and Pristina.

However, Kosovo’s Prime Minister, Albin Kurti, decided to go ahead with the installation of ethnic Albanian mayors in the north, who were sworn in with the protection of the country’s police (KP) and police special forces (ROSU). This sparked new large-scale protests by Serbs in the north. The appointment of ethnic Albanian mayors has sparked outrage also in the United States and the European Union, with the US even evoking political sanctions against Kosovo and the so-called ‘Quint’ condemning the moves of Pristina. Finally, on the acme of the crisis, on the 29th of May KFOR soldiers in riot control deployment clashed with Serb protesters in Kosovo. More than 70 people were injured, including 30 NATO military personnel (among which Italians, from the biggest contingent, and Hungarians). The protests continued afterwards, peacefully.

The combination of ongoing anti-government protests in Serbia and escalating tensions in northern Kosovo poses a significant risk of regional destabilization and threatens to derail the dialogue between Belgrade and Pristina, which has been making important progress in the past months. Additionally, the increasingly radical actions of Prime Minister Kurti in Kosovo could result in a complete failure to implement the agreements reached earlier this year, both in Brussels and Ohrid. Meanwhile, in Belgrade, the hold on power by President Vucic, who has been supported by the West as a promoter of a normalization agreement with Pristina, appears to be facing significant challenges.

Further News and Views

US diplomats and politicians discuss about future of the Balkan region

Sources: Radio Free Europe, N1, Balkan Insight

Derek Chollet, a counsellor at the US State Department, and Gabriel Escobar, the US Special Envoy for the Western Balkans, provided testimony to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee regarding their efforts to facilitate the integration of Balkan countries into the European Union and strengthen ties with the West and NATO. They acknowledged the progress made since the conflicts of the 1990s, but also highlighted persisting challenges, including the presence of autocratic leaders, corruption, weak rule of law and dependence on Russian energy. Escobar specifically emphasized the need for targeted constitutional reforms in Bosnia to facilitate EU enlargement. Both Chollet and Escobar expressed concern about Russia’s efforts to undermine Serbia’s path towards European integration. They also identified Milorad Dodik, the President of Bosnia’s Republika Srpska (RS) entity, as a key factor contributing to the country’s instability. Additionally, concern was expressed over the failure of Kosovo and Serbia to implement the dialogue agreements reached in Brussels and Ohrid.

EU pushes the Balkans closer to the bloc with new plan for growth

Sources: Euractiv, European Commission

EU Enlargement Commissioner Oliver Varhelyi stated at the “EU Meets the Balkans conference” in May that this year will be critical for EU enlargement. The emphasis of Brussels is now on quickly integrating the Western Balkans economies, as their development prior to joining the EU will contribute to a more successful integration process later on, the Commissioner claimed. EU Commission President Von der Leyen also announced a new growth strategy for the Balkans aimed at bringing some of the benefits of EU membership to the region before full integration. Bringing the Western Balkans closer to the EU Single Market, deepening regional economic integration, accelerating fundamental reforms, and increasing pre-accession funds are all part of the plan, she said. This represents a EU’s new approach to assisting the Western Balkans and promoting their integration into the European community, Von der Leyen stressed.

EU - NATO

NATO increased presence in Kosovo, Serbian army on high alert

Sources: NATO, BBC

NATO decided to increase its presence in the former Serbian province of Kosovo in response to the serious incidents in the north of the country.

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg strongly condemned the violence in northern Kosovo against the troops of the KFOR mission, calling it unacceptable. He also reassured that KFOR will take all necessary steps to ensure the safety of citizens in Kosovo, acting impartially in accordance with its United Nations mandate. For this purpose, NATO will deploy an additional 700 troops (+18,6%) from the operational reserve force to the Western Balkans, as a precautionary measure. The Alliance also decided to increase the readiness of a multinational reserve battalion. Stoltenberg emphasized that violence impedes progress in Kosovo and the region, putting the European aspirations of both Belgrade and Pristina at risk. He urged at the same time both Serbia and Kosovo to de-escalate the situation, refrain from irresponsible behaviour, and participate in the EU-facilitated dialogue for reaching a long-term peace.

Meanwhile, in the aftermath of the first clashes between police and the Kosovo’s Serb demonstrators in the town of Zvecan, Serbian President Vucic responded by placing the Serbian army on high alert and by stationing armed units near the Kosovo border, a move already seen in some past crises.

ECONOMICS

Balkans explore ways to improve trade and foster growth

Sources: World Bank, Emerging Europe

While tensions between Serbia and Kosovo rise, governments in the region continue to work together to promote economic relations and growth, the way to go. The importance of trade integration for the economies of the Western Balkans in order to become more competitive and grow faster was emphasized at a high-level conference held in Belgrade in May, organized by the World Bank, USAID, and the Swiss government. The goal was to help Western Balkan countries improve institutional capacity and trade protocols, and to simplify, expedite, and secure the movement of goods across borders. Regional economic integration via trade and connectivity is viewed as an important driver of economic growth and shared prosperity in the Western Balkans, the World Bank said. “The economic future of the Western Balkans is dependent on the respective governments’ ability to facilitate seamless trade, reducing the time and cost of moving goods across borders,” the US Ambassador to Serbia Christopher Hill noted. Meanwhile, the Western Balkans’ economies have recovered from the pandemic and surpassed pre-crisis levels, according to the World Bank.

Stefano Giantin

Journalist based in the Balkans since 2005, he covers Central- and Eastern Europe for a wide range of media outlets, including the Italian national news agency ANSA, and the dailies La Stampa and Il Piccolo.