Press Reviews

June 2021

International Media Digest

US WILL SANCTION THREATS TO STABILITY IN THE REGION

The Biden administration is getting more involved in the Balkans, evoking sanctions against individuals and political leaders who might threaten the stability of the region, amid a push to speed up the integration of Western Balkan countries into the European Union.

On 9 June President Biden signed an executive order that updated the existing policy of sanctions in the Balkans by targeting persons, including political leaders, “who threaten the peace, security, stability, or territorial integrity of any area or state in the Western Balkans as well as those responsible for (…) serious human rights abuse or in episodes of corruption in the Western Balkans,” the Department of State said.

The new policy allows sanctions also against individuals that undermine the implementation of regional agreements and verdicts of the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (MICT), the successor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). Additionally, order allows sanctions against persons who challenge mutual recognition agreements, such as the Prespa agreement between North Macedonia and Greece. The wording suggests Washington might use sanctions in case political leaders undermine a final agreement between Serbia and Kosovo.

The sanctions include the freezing of all properties of persons designated. Sanctioned individuals will be banned from entering the United States or holding a US visa.

“Our commitment to promoting democracy, transparency, and accountability, across the Western Balkans is both unwavering and consistent with the standards the countries of the region must meet to secure their goals of advancing on the European path,” told US Secretary of State, Anthony J. Blinken. Washington already sanctioned several influential politicians from the region in the previous years. Among them, the current Serb member of the Bosnian tripartite presidency, Milorad Dodik, who was sanctioned back in 2017 for its nationalistic policies. More recently, the former Albanian Prime Minister and former President Sali Berisha and influential business people and public officials from Bulgaria were targeted for their alleged involvement in corruption cases.

Biden’s executive order represents a break from the policy of the Trump administration towards the Balkans, which was focused more on economic development than on solving open issues. For the United States, the Balkans represent now a priority, as confirmed by the US–EU Summit Statement. “We intend to strengthen further our joint engagement in the Western Balkans, including through the EU-facilitated dialogue between Belgrade and Pristina on normalisation of their relations, and by supporting key reforms for EU integration,” the statement reads.

The EU however, is not considering at this stage support for the US in targeting persons in the Balkans with sanctions.

NATO SUMMIT AND THE BALKANS

The leaders of NATO member countries met in Brussels in June to discuss the global challenges coming from Russia and China and the Alliance’s future in the next decade. US President Biden attended the summit for the first time since he took office.

The Western Balkans, and the integrity of Bosnia and Herzegovina, were also a topic on the agenda. According to the Brussels Summit Communiqué, the region remains “of strategic importance for NATO” and the Alliance is “strongly committed to the security and stability of the Western Balkans and to supporting the Euro–Atlantic aspirations of the countries in the region.”

Albania, Montenegro and Northern Macedonia already joined NATO, together with the EU member countries Slovenia and Croatia. NATO leaders reaffirmed that NATO “supports the sovereignty and territorial integrity of a stable and secure Bosnia and Herzegovina in accordance with the General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina and other relevant international agreements.”

The reference to the 1995 Dayton Peace agreement was of particular importance for Croatia, with President Zoran Milanovic pushing for having that part included in the final statement. Bosnia and Herzegovina remain deeply divided, with Bosnian Serb leaders frequently threatening to secede from the country and part of the Croatian leadership in Zagreb and in Bosnia and many Bosnian Croats still advocating for the creation of a third Croatian-led entity in the country. NATO leaders encouraged “domestic reconciliation, and urge political leaders to avoid divisive rhetoric” in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the statement reads.

Referring to the Serbia–Kosovo dialogue, the Alliance remarked on the necessity of reaching “a lasting political solution” that would normalise the relationship between Belgrade and Pristina. Moreover, “strengthening NATO–Serbia relations would be of benefit to the Alliance, to Serbia, and the whole region.”

Further News and Views

EU working on investment plan for the Balkans

The European Union is working on a significant economic plan for the recovery and development of the Western Balkans, capable of attracting almost 30 billion euro in investments in the area, one third of the entire GDP of the region. The plan, outlined in October 2020, foresees the direct mobilisation of 9 billion euro from the EU through the so-called Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance funds, with the potential of attracting another 20 billion, the EU Enlargement Commissioner Oliver Varhelyi said. The plan represents the EU’s “greatest historic move toward the Western Balkans”. It will lead to “a fundamental improvement of the road, railway and port infrastructure, interconnectivity, energy sector and digitalisation,” said the Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama.

The Associated Press, European Western Balkans

Albania, North Macedonia still in the EU waiting room

The European Union could launch accession talks with Albania and North Macedonia this year, most probably during the upcoming Slovenian presidency, which begins on 1 July. The diplomatic efforts of Portugal, which currently holds the presidency of the EU, to overcome in particular the Bulgarian veto against North Macedonia, could pave the way for the “opening of the first intergovernmental conference with these two countries within the Slovenian presidency, in the second half of this year,” the German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas said during a virtual meeting of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the Berlin Process. North Macedonia recently received the backing of Austria, the Czech Republic, and Slovenia to start talks with the EU, while the Dutch Parliament agreed that Albania had met all conditions to launch negotiations.

Balkaneu, Bloomberg, Euractiv, Radio Free Europe

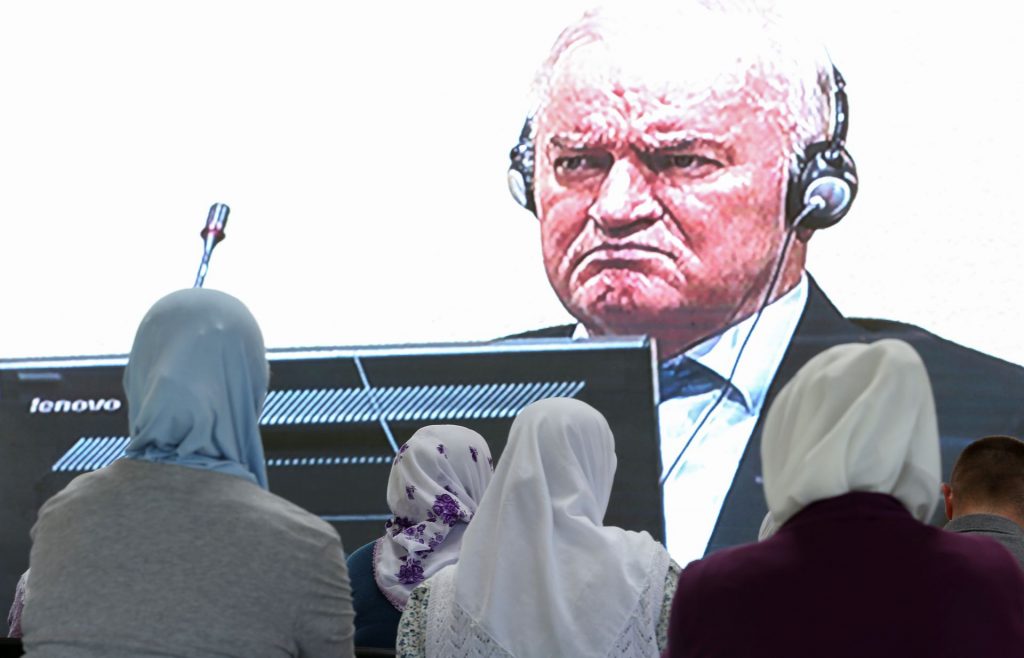

Genocide conviction upheld against Mladic

The International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (MICT) has upheld the life sentence conviction against the former Bosnian Serb general Ratko Mladic. Mladic lost the appeal against the 2017 verdict of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, the predecessor of MICT, for the genocide committed in Srebrenica in 1995 and for other serious war crimes and the ethnic cleansing campaign conducted during the conflict in Bosnia. The trial against Mladic was the last major ongoing trial related to the massacres in former Yugoslavia. Last year, the MICT also upheld the conviction for genocide of the wartime Bosnian Serb political leader Radovan Karadzic, increasing his sentence to life in prison. Both Mladic and Karadzic are still regarded as heroes by many Serbs in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

BBC, Reuters

CoE warns of increasing ethnic tensions in Montenegro

Divisions between different ethnic communities in Montenegro are deepening, according to a report of the Council of Europe (CoE) on the Convention for the Protection of National Minorities’ implementation. Montenegro got independent from Serbia through a referendum in 2006. Only about 45 per cent of its population identify themselves as Montenegrins, 29 per cent as Serbs, 11 per cent as Bosniaks Muslim and 5 per cent as Albanians. Montenegro witnessed significant political tensions due to a conflict between the previous government and the powerful local Orthodox Church. In the past months, social distances between almost all ethnic groups have increased, CoE said.

Balkan Insight

Youth unemployment reaches 35,1%, but recovery expected

The average youth unemployment rate in the Western Balkans was 35,1 per cent in 2020, more than double the European Union rate of 16,9 per cent, a study of the Regional Cooperation Council (RCC) showed. The youth unemployment rate in the region, a severe issue that exacerbates the issues of the brain drain from the region, increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, the RCC said. According to recent World Bank estimates, the economic crisis induced by the pandemic led to almost 140.000 job losses in the Balkans and between 165.000 and 336.000 people in the region were pushed into poverty. However, after a contraction of 3,4 per cent last year, the region is expected to grow by 4,4 per cent in 2021.

RCC, World Bank

Monthly Analysis

SERBIA AND KOSOVO RESTART TALKS,

FAIL TO MAKE PROGRESS

For the first time in almost a year, Belgrade and Pristina relaunched long-awaited European Union-led bilateral talks to normalise their relations. Still, they failed to make any real progress.

The dialogue is led by the President of Serbia, Aleksandar Vucic, and Albin Kurti, a left-wing nationalist and reformist who became Kosovo’s Prime Minister after a landslide victory in February’s elections. Kurti and Vucic met for the first time in Brussels. The positions of Belgrade and Pristina remain very distant and the chance of a solution in one of the most intractable territorial disputes seems remote.

After the meeting, hosted by the European Union Special Representative for the Belgrade-Pristina Dialogue, Miroslav Lajcak, and the European Union High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Josep Borrell, Vucic hit out at Kurti. The Serbian leader claimed that Kosovo Prime Minister “demanded” that Belgrade recognises the independence of Kosovo and refused to discuss the implementation of a 2013 agreement that foresees the creation of a Community of Serb-majority municipalities in Kosovo, a key step for Belgrade to advance the talks with Pristina. Kurti “asked me when are you going to recognise independent Kosovo. I told him never, and he exploded,” Vucic said.

Kosovo and Serbia separated de facto after the 1999 war. Pristina declared its independence from Belgrade in 2008 and has been recognised by more than 100 countries. Serbia still considers the territory as its southern province, a position supported by Russia and China and by five EU member countries (Slovakia, Greece, Romania, Spain and Cyprus), which do not recognise Kosovo as an independent state.

On the other side, PM Kurti noted that Pristina “brought four new proposals which were refused by the Serbian side,” and claimed that Vucic refused to even consider them. However, Kurti defined the summit as “constructive,” without elaborating further.

The EU admitted that no concrete results were achieved in the first meeting between Vucic and Kurti, expressing hope that steps forward will be observed at their next meeting, at the end of July. Even if Borrell spoke of a “new momentum” in solving the open issues between Belgrade and Pristina, Lajcak was more outspoken. “Both leaders had a very open and frank exchange on what they each want from the dialogue,” but “it was not an easy meeting,” the EU envoy Miroslav Lajcak admitted.

There are many disputes to be resolved between Kosovo and Serbia. The main one is the refusal of Belgrade to recognise Kosovo’s independence, while Pristina claims that nothing else can be discussed until that reality is accepted by the Serbian side. The latter is fighting to keep Kosovo out of main international organisations and reacted with anger when Pristina managed to get admitted in the World Bank, IMF and FIFA and UEFA. The Serbian Constitution says explicitly that Kosovo is part of Serbia. Pristina also hinted at the possibility of asking Belgrade to pay war reparations and to sue Serbia for genocide.

For Belgrade, one of the most crucial points in the dialogue is the protections of its cultural and religious heritage, the churches and orthodox monasteries in Kosovo, considered by Serbs as the cradle of their nation. Moreover, Belgrade is keeping a strong link with the 120.000 Serbs who still live in the former Serbian province and remain loyal to Belgrade, because their salaries and pensions are paid by Serbia. A 2013 deal brokered by Brussels paved the way for the creation of an association of 10 Serb-majority municipalities in Kosovo, but the agreements has never been implemented as the two sides cannot agree on how it would work, with Pristina fearing the creation of a “Republika Srpska” in Kosovo.

The Insight Angle

EDWARD P. JOSEPH

Senior Fellow & Lecturer,

JOHNS HOPKINS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED INTERNATIONAL STUDIES (Washington DC)

Serbia and Kosovo restarted talks in June but failed to make any progress. Do you expect a breakthrough in the following months?

I don’t expect a breakthrough — and I never rule one out either. The dynamics for a breakthrough are not good –– and not just for the obvious reasons, e.g. Serbia holding elections next year or Kosovo having recently held decisive elections. People imagine that these very different circumstances lead to the same circumstance: a disinclination to deal.

I think the real obstacles to a breakthrough are deeper than election cycles. There is a serious power imbalance, a serious difference in interest in the outcome, a serious difference in approach to democracy, a serious difference in international orientation and affinity. And, of course, there are the actual, intrinsic differences of a conflict in which the perceptions of needs are starkly different.

What kind of agreement Serbia and Kosovo could reach?

First, anyone who was concerned by the reverberations across the Balkans in April after a lone, anonymous “non-paper” was released on a Slovenian web portal, could not even contemplate the land swap. This proposal sent tremors about the possibility of new conflict.

Second, neither “land swap” nor “Two Germanys’ is necessary to resolve the Kosovo dispute.

Every negotiation hinges on relative power, in addition to some other factors. It is not just about the positions of the sides; it is about the ability to achieve those positions –– and to sustain any cost for sticking to the positions.”

It is helpful to compare to other situations. For example, in what is now North Macedonia, there was a time when maps were produced showing “Agean Macedonia” belonging to what was then the Republic of Macedonia. This included the city of Solun, the Macedonian word for Thessaloniki. These maps were highly provocative. They were also never taken terribly seriously in North Macedonia for the straightforward reason — power. There was no way that this territory belonging to Greece would somehow become Macedonian.

Relative power is the same reason that the “name issue” dragged on so long. Athens could “prevail” simply by maintaining the status quo — resisting calls to allow Skopje into NATO and to open negotiations with the EU. As a member of NATO and the EU, Greece held the power advantage.

This is exactly my thesis on Serbia and Kosovo (in my Wilson Center paper and in the recent Foreign Policy article). Serbia’s position on Kosovo is a hard line because Belgrade holds the leverage. If it didn’t hold the leverage, then the sides would have a “Prespa-like” negotiation and settle the issue in a dignified, stabilising way, with the aid of EU mediation and active US engagement. There would be no dangerous land swap or inapposite “Two Germanys.”

How important are the divisions inside the EU in keeping Kosovo’s question unresolved?

These divisions — the refusal of five EU countries/four NATO countries to recognise Kosovo

are the single biggest obstacle to stability in the Balkans. The position of the EU 5/NATO 4 is the single biggest advantage the West gives to Russia and China.

These divisions inflict serious damage on EU and NATO interests, on Kosovo’s stability and population, or the stability of neighbouring countries, and, ironically, these divisions inflict serious damage on Serbia, preventing the country from finally making the decisive break to embrace the Western order. The reason is simple: the position of the EU 5/NATO 4 hands Serbia the leverage over Kosovo, and over the Kosovo negotiations.

It is not for the Russian and Chinese vetoes at the UN Security Council, but because of the five EU/four NATO countries that don’t recognise Kosovo. If only the four NATO countries (Cyprus is not a member of the Alliance) recognised Kosovo, the entire situation would be transformed. Kosovo would have a pathway to the Alliance, to security, to solid international personality. And that would end Serbia’s strategy of isolating and weakening Kosovo. Belgrade would be faced with two options: to continue to isolate Kosovo to no avail, watching and grumbling as it becomes stronger and more accepted; or to negotiate seriously.

In other words, the possibility for a Prespa-like negotiation would suddenly come into focus. It is not only about the final terms, but also the context for the negotiation — one in which the power balance becomes more equitable. So, for me the way forward is clear, work with the five EU non-recognisers/four NATO non-recognisers to modify their positions, even if they cannot recognise Kosovo. The closer the EU 5/NATO 4 move towards recognition, the more they erode Serbia’s leverage, and the closer they bring Belgrade and Pristina to resolution of this dispute.

How do you read the “modernization” of US sanctions for the Balkans?

The recent executive order from President Biden is a significant step— potentially one of the most significant in the region in decades. It’s a statement of serious commitment by the Administration to the region — to seeing that the peace agreements that have been signed are implemented, and a commitment to stemming rampant corruption, which is a major obstacle to stabilising the region.

The question I raised in my recent Foreign Policy article is whether this major policy commitment will be applied evenly around the region, including the country with the most sophisticated and extensive system of corruption: Serbia. I noted that, up to now, the US and EU have a paradoxical stand; Washington and Brussels give the most favourable treatment to the most anti-democratic country. That needs to change, as part of a wider shift in policy to hold all the region’s aspirants accountable to their commitments.

The EU integration process seems to be stalled. How dangerous is that for the region?

This is quite dangerous, and a serious mistake in ways that European countries do not really appreciate. For example, take the concept of European “strategic autonomy.” How can Europe aspire to a meaningful security role anywhere, if the EU cannot finally stabilise the Balkans without clear, continuing dependence on the US? One can imagine the chortling in the Kremlin when this concept comes up. Any savvy Russian analyst will say, “the Europeans can’t sort out Kosovo or Bosnia, how are they going to act without the US in the Middle East?” Individual EU states like France (or the UK, when it was in the EU) have and continue to act decisively in select situations in Africa. But it is hard to see how Europe can harbour wider ambitions without the ability to resolve the ethno-national stand-offs in the Balkans.

It’s worth thinking about all the advantages that the EU enjoys in the Balkans that are not present, say, in the Middle East.

It’s also worth thinking about the uproar just two months ago (in April) over the purported “Slovenian non-paper.” How often does an anonymous paper on an independent website send tremors about potential resumption of conflict across a region and much of Europe? It’s a completely unnatural event.

To me, it’s proof that there is a crisis of confidence in Western strategy — which should have been noticed already with all the outmigration from the region, amidst the continuing uncertainty and ethno-national divisions. At the root of this crisis of confidence are both European disingenuousness about enlargement and those crippling European divisions over Kosovo. They are not the mark of a continent ready to fully assume responsibility for its security.

Stefano Giantin

Journalist based in the Balkans since 2005, he covers Central- and Eastern Europe for a wide range of media outlets, including the Italian national news agency ANSA, and the dailies La Stampa and Il Piccolo.