Monthly Journal

by the international press on the region, enriched by relevant commentaries and analyses.

The journal aims to create a better perception of the region

through authoritative international sources.

Something that is currently missing.

This project is realised with the support of the Fondazione Compagnia di San Paolo.

April 2024

International Press Review

The most relevant events of the area through international sources

Kosovo Serbs boycott referendum organised to remove ethnic-Albanian mayors

Reuters

Most Serbs in the north of Kosovo boycotted a referendum aimed at removing ethnic Albanian mayors in four municipalities after their contentious appointment. Last September, Pristina’s government agreed to nullify local elections in Kosovo’s north and conduct new ones, responding to Western pressure after local Serbs largely boycotted the April 2023 vote. Pristina’s proposal for a pre-election referendum on dismissing the mayors was surprisingly opposed, however, by the leading local Serbian List party, which argued for their resignation before the vote. The Serbian List claimed the referendum’s integrity was compromised by pressure and intimidation from the Kosovo government, allegations that Pristina refuted.

Right-wing nationalist candidate ahead in presidential vote in North Macedonia

Radio Free Europe

Gordana Siljanovska-Davkova, representing the nationalist VMRO-DPMNE party, currently in opposition, secured a significant lead in North Macedonia’s presidential elections, earning 40% of the votes at the first round. Incumbent pro-European Stevo Pendarovski, of the Social Democratic Union (SDSM), trailed with almost 20% of votes. Despite her lead, Siljanovska-Davkova didn’t attain enough votes to avoid a runoff. With North Macedonia’s 2.3 million citizens eager to see their country in the EU, and Bulgaria continuing to block the opening of EU membership talks with Skopje, the EU integration remains a prominent campaign theme alongside combating corruption and poverty. The second round of the presidential elections will be held at the beginning of May, together with the parliamentary elections.

Ruling party wins elections in Croatia, uncertainties ahead

Al Jazeera

The ruling HDZ party has secured the most seats in Croatia’s parliamentary election, but it faces challenging negotiations to secure a parliamentary majority and to form a stable coalition government. Prime Minister Andrej Plenkovic’s HDZ won 60 seats, down from 66 in the previous 2020 vote. The centre-left coalition, led by the Social Democrats (SDP) of President Milanovic, won 42 seats, while the right-wing Homeland Movement came third with 14 seats. Plenkovic managed to prevail despite voter fatigue, high inflation, and corruption scandals, relying on the HDZ’s long-term support for Croatia’s EU accession and NATO integration, the benefits of the introduction of euro, and tourism strong growth.

Still no solution in sight for the dinar ban in Kosovo

N1

Notwithstanding talks in Brussels in April, diplomatic delegations from Belgrade and Pristina failed to reach an agreement on the use of the Serbian dinar in Kosovo. The currency, used by the Serbian community in Kosovo, had been earlier declared illegal by Kosovo’s authorities. Pristina’s negotiator, Besnik Bislimi, expressed concern, alleging that Serbia aims to finance illegal institutions in Kosovo until the formation of the Association of Serb Municipalities. Previously, outgoing EU special envoy Miroslav Laicak said he had presented a “compromise paper” on the dinar to both parties, but to no avail.

Kosovo risks EU integration without Association of Serbian municipalities

Euronews Albania

EU spokesperson Peter Stano emphasized the urgent need to make sure that Kosovo establishes an Association of Serb-majority municipalities, warning of negative consequences for its EU integrations if it fails to do so. This obligation, reiterated by EU leaders in several occasions, stems from agreements reached in 2013 and 2015 between Kosovo and Serbia. However, the Constitutional Court of Kosovo ruled in 2015 that the agreement was not fully constitutional, and PM’s Kurti government fiercely refuses to give a green light to the Association.

Russian spy wanted to destabilize Slovenia ahead of NATO anniversary

STA

A Russian diplomat expelled by Slovenia in March was reportedly trying to disrupt Slovenia’s 20th NATO accession anniversary celebrations using a network of associates. Unofficially, their main aim was to fuel negative public sentiment against NATO and undermine trust in the government by sowing discord in Slovenian society. Following the expulsion of the diplomat, several Russian citizens suspected of exploiting the study exchange system to acquire residency papers in Slovenia, probably part of a network of associates of the diplomat, also departed the country.

Hungarian politicians suspected of promoting pro-Moscow propaganda

444.hu

Der Spiegel and Der Standard revealed the existence of a propaganda network allegedly linked to Moscow, funnelling funds to politicians from Hungary and some other Central and Eastern European countries, to promote pro-Russian agendas within the EU. The funds were used for campaigns ahead of European Parliamentary elections. Czech Prime Minister Petr Fiala disclosed details, including the network’s use of the Prague-based news outlet, Voice of Europe, known for spreading pro-Russian narratives.

Another NATO battalion deployed to Bosnia and Herzogovina

TVP

NATO deployed a reserve battalion to Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) in an effort to bolster the ongoing ALTHEA mission conducted by the European Union force (EUFOR), the Deputy Speaker of the House of Representatives of BiH and former Prime Minister Denis Zvizdic announced. Zvizdic described the decision as “long-awaited and strategically important,” emphasizing its potential to quell secessionist ideas and maintain peace. He highlighted the deployment as a “preventive action aimed at preserving peace in BiH, the region, and the European Union”.

Belgrade includes pro-Russian politicians under US sanctions in new cabinet

Balkan Insight

Milos Vucevic, set to succeed Ana Brnabic as Serbian Prime Minister, confirmed that Aleksandar Vulin, a pro-Russian figure sanctioned by the US and former head of Serbia’s Security Information Agency, will serve as one of the deputy prime ministers in the new cabinet. Additionally, Nenad Popovic, another controversial pro-Russian politician under US sanctions, will become a minister without portfolio. Vucevic’s appointment to the prime minister’s position was first announced by the Serbian President Vucic the 30th of March.

Romania is key for the defence of the Eastern NATO flank

Balkan Insight

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg and Romania’s President Klaus Iohannis discussed security in Ukraine and the region during a meeting in April. Stoltenberg highlighted Romania’s vital role in defending NATO’s eastern flank and in supporting Ukraine. Iohannis emphasized his country’s focus on Ukraine and the Black Sea region. Recently, he announced his candidacy for the position of NATO Secretary General, but Iohannis chances of success remain low.

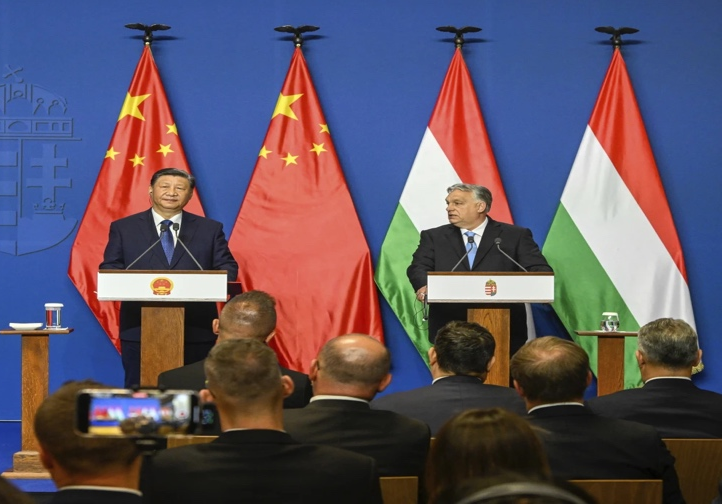

Chinese President Xi to visit Hungary and Serbia

Bloomberg

President Xi Jinping is poised to visit Belgrade around the 25th anniversary of the US bombing of the Chinese embassy, an event that fuelled anti-US sentiment in China and increased Beijing’s distrust of NATO. Xi’s visit to the Balkans, scheduled at the beginning of May, marks his first trip to Europe since the pandemic. During the 1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia, US missiles reportedly mistakenly destroyed the embassy in Belgrade and killed three Chinese journalists, sparking controversy. Xi will also visit Hungary, one of the EU’s countries closest to China, and France.

NATO keeps reinforcing its Eastern flank, new plans for Bulgaria and Romania

Novinite

As tensions in the Black Sea region rise due to Russian invasion of Ukraine, NATO announced plans to strengthen its military presence by establishing a new base in Bulgaria with 5.000 troops. Meanwhile, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, at the Second Black Sea Conference in Sofia, reaffirmed US commitment to regional security and countering disinformation, stressing the need for unity against emerging threats.

The Insight Angle

Branimir Jovanovic

serves as an Economist at the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (WIIW), a prominent European think tank known also for its expertise on the Balkans. His current research interests primarily revolve around economic inequality, poverty, fiscal policy, taxation, social policies, foreign direct investment (FDI), EU integration. In the past, his research encompassed areas such as monetary policy, exchange rates, international trade, financial crises, and forecasting. Furthermore, Jovanovic has had important advisory roles, notably serving as an adviser to the Minister of Finance of North Macedonia from 2017 to 2019 and previously as a researcher at the Central Bank of North Macedonia from 2007 to 2015.

The European Union’s new “Growth Plan” for the Western Balkans was described by Brussels as a historic opportunity for the region to close the gap with the EU and stimulate economic growth. What are the plan’s main benefits for the Balkans? What is different about this plan compared to previous EU initiatives, and can it truly accelerate convergence with the EU?

I see two main benefits for the Western Balkans. The first is that the Plan explicitly discusses opening the EU single market to the region. The second is that, for the first time, the Plan firmly anchors the initiative for a Common Regional Market within the EU accession process. Previously, some interpreted the Common Regional Market as a substitute for EU membership, now it’s clear that it’s not.

On the other hand, I still think that the “New Growth Plan” is not really new. The Common Regional Market has been around for almost 10 years. The financial component of the “New Growth Plan” constitutes just 20% of the existing “Economic and Investment Plan”. Therefore, my overall verdict is that the “New Growth Plan” essentially represents “more of the same” and not a “game changer.”

Hence, I am sceptical that the Plan will significantly accelerate economic convergence with the EU. Why would we expect that the “New Growth Plan” will foster convergence when the “Economic and Investment Plan,” which was five times larger, failed to do it?

You have criticized the plan, stating that it “falters upon closer inspection.” What are the most significant issues you discovered with the plan?

I’ll focus just on the first two pillars of the Plan. The first pillar, enhancing the Common Regional Market, is totally fine, but has achieved only little over the past decade. Its key problem has been the neglect of the region’s political challenges, especially the status of Kosovo. These challenges repeatedly obstruct regional cooperation, even when it comes to most everyday things, such as free travel and diploma recognition. Although the Plan can’t promise to resolve these issues, it should acknowledge them and commit to intensified diplomatic efforts for their resolution.

The second pillar—opening the EU single market to the Western Balkans—sounds promising. Allowing people from the region to work in the EU, without special permits, or enabling firms from the region to export as easily as those from Bulgaria (for example), would significantly advance integration into the EU family. Unfortunately, the Plan doesn’t do this. As a citizen of a Western Balkan country working in the EU, I will still face the same complex work permit procedures after this Plan. Similarly, Western Balkan firms aiming at exporting to the EU will still need various documents for this purpose.

The distribution of funds is linked to reforms and efforts to promote internal normalization within the region. Do you think the incentive of €6 billion is substantial enough to persuade local leaders to act?

Unfortunately, I don’t think so. Of the 6 billion EUR allocated, only 2 billion are grants. The remaining part are loans, which are far less attractive. This grant allocation spreads over four years, amounting to merely 500 million per year for the entire region—just 0,3% of the annual regional GDP, which is insufficient for a bigger impact. Moreover, the conditions attached to this funding are stricter than those for current IPA funds, which are already underutilized.

I understand the idea to introduce tougher conditions, to stimulate the stagnant reform agenda in the region. But for this approach to work, the financial incentives need to be much larger. Using the well-worn metaphor of the carrot and the stick: if a larger stick is employed, a correspondingly larger carrot must also be provided. Currently, the Plan offers only a bigger stick.

Do you believe the EU can modify the plan to make it more effective? What specific changes would you suggest?

The part of the Plan where I still see scope for adjustments is the opening of the EU market to the Western Balkans. This part is the least developed, but also the one that can have perhaps the biggest impact on the region. The most important things I would suggest here are: to provide financial and technical assistance to Western Balkan companies that want to export to the EU (for obtaining necessary certificates and export documentation); to eliminate, or at least reduce, EU border controls for companies from the region; and to reduce or, preferably, eliminate work permit requirements for citizens from the Western Balkan countries seeking employment in the EU.

While the Western Balkans remain distant from full EU integration, the region is working on initiatives such as the “Open Balkan” to promote greater integration within the area. Do you think such projects could benefit the region?

I think Open Balkan is already benefiting the region, first and foremost by improving the political relations between the countries which are in it. Relations between Serbia and Albania are currently better than ever, largely due to Open Balkan. I am very pragmatic when it comes to this, and for me anything that helps improve relations in the region is good. But I definitely think that the initiative must be expanded to include all the countries from the region. Starting with Montenegro, and then Bosnia and Herzegovina, and then, if they join, Kosovo will find it very hard to stay outside. At the present, it’s not really an Open Balkan, it’s more like a Half Balkan.

With EU integration still facing hurdles, do you have an estimate of how long it might take the Western Balkans to achieve a satisfactory level of convergence with the EU in terms of living standards and economic development?

The numbers are quite depressing. The Western Balkans’ income levels are currently around 40% of the EU’s, adjusted for purchasing power. If the region grows annually by one percentage point more than the EU—for instance, if the EU grows at 2% every year and the Balkans at 3%—it would still take 90 years for the Balkans to match EU income levels. If the Balkans can accelerate their growth to 4% while the EU maintains at 2%, this gap could be halved to 45 years. Although the outlook isn’t optimistic, the critical takeaway is the urgent need for the Balkans to substantially boost their growth rates.

The Key Story

Strategic trends

Belgrade angry after Kosovo gets (almost) final green light for joining the Council of Europe

The already tense relations between Serbia and Kosovo faced further strain as Pristina moved one step closer to joining the Council of Europe in April, raising concerns about potential negative consequences in the geopolitical arena in Europe.

The Council of Europe (CoE) is the oldest and most authoritative international organization dedicated to protecting and promoting human rights, democracy, and the rule of law in Europe. Established in 1949, it includes 46 member states. For Kosovo, joining the Council of Europe represents a strategic objective aimed also at promoting its international recognition, a goal vehemently opposed by Serbia. However, Kosovo’s objective appears increasingly attainable.

After the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly Committee on Political Affairs and Democracy voted in favour of Kosovo’s application for membership last March, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe made another historic vote recommending Kosovo’s accession. 131 members of the Assembly voted in favour of Kosovo’s membership, while 29 voted against, and only 11 abstained from the vote. Unsurprisingly, Serbian officials have expressed objections to this recommendation.

In a so-called statutory Opinion, based on a report by Dora Bakoyannis, former ministry of Foreign Affairs of Greece, and passed by the Assembly, the Council stated that Kosovo’s membership would lead to “the strengthening of human rights standards by ensuring access to the European Court of Human Rights for all those who are under Kosovo’s jurisdiction”. Kosovo’s membership in the Council of Europe would also signify “the culmination of a dialogue which has developed over a span of two decades but should in no way be seen as the end of a process. On the contrary, membership should catalyse momentum for Kosovo to continue to make progress in strengthening human rights, democracy, and the rule of law”.

The Assembly also confirmed that Kosovo is ready to join, as proved by “a major breakthrough” achieved this year, i.e. the implementation of the Constitutional Court’s judgment in the case of the Visoki Decani Serbian orthodox monastery, which was “a tangible sign of the commitment of the government to act in full accordance with the rule of law, irrespective of political considerations”.

Furthermore, “since the very beginning I have been adamant that the report will take no stand on statehood” and “the recognition or non-recognition is and shall remain a prerogative of states,” Bakoyannis noted.

On the opposite side, Serbia’s stance perceives Kosovo’s potential membership in CoE as a violation of international law and as an attempt by Western powers to further isolate Belgrade. “You will go down in history as someone who, in the most brutal manner, violated all the norms of international law in the principles upon which this organisation is founded,” Serbian representative Biljana Pantic Pilja told the Assembly, noting that it was “decided to trample on international law and admit into the Council of Europe something that is not a state, bypassing all procedures.”

Belgrade is also angry as one of the pre-conditions for letting Kosovo in the Council was the establishment of the Community of Serb Majority Municipalities, which was still not formed. “What you are doing is a precedent by which you will open Pandora’s box. You have proved that territorial integrity and sovereignty mean nothing to you, and maybe precisely one of your states is next and will follow this precedent that you have created in Serbia’s case,” Pantic Pilja underlined, suggesting there might be similar problems in the countries that don’t recognize Kosovo, for instance Spain, or Romania.

Kosovo’s government, on the other hand, is concerned that such an association could, in the medium-long term, serve as a territorial platform for a potential secession of Northern Kosovo or as the basis of a new Republika Srpska. In May 2023, Kosovo’s Prime Minister Albin Kurti stated, “What we will not allow is the right to territorialize and create anything that would resemble Republika Srpska in Bosnia. We will not permit a satellite entity with a destructive essence that would undermine Kosovo’s citizenship.”

Outgoing Serbia’s Foreign Minister, Ivica Dacic, also condemned the recommendation for Kosovo’s membership in the Parliamentary Assembly, labelling it as a “day of shame” due to Kosovo’s non-state status and perceived failure to meet basic requirements in human rights and freedoms. Serbian President Vucic also expressed concerns that if Kosovo joins the CoE, “it will use its new international legal position to sue Serbia for international crimes” committed against the Albanians in Kosovo during the 1999 war. Belgrade might even exit the Council of Europe, if Pristina joins.

The ultimate decision will, however, be rendered by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe in May. This group is comprised of the foreign ministers of the 46 member states, encompassing also nations that have not officially recognized Kosovo’s independence.

If the Committee of Ministers also gives the green light and allows Kosovo to join the Council of Europe, it will deal a major political and diplomatic blow to Serbia – and it is currently hard to predict how Belgrade will react – while representing a highly significant victory for Kosovo, nearly as important as joining the EU or NATO.

Further News and Views

UN General Assembly postponed vote on Srebrenica resolution

Sources: N1, Euronews, Voice of America, UN

A vote in the UN General Assembly on a contentious resolution regarding the Srebrenica genocide, initially set for the 2nd of May 2, has been postponed and will not occur before the 6th of May, according to diplomatic sources at the United Nations. This marks the second delay of the resolution, which was originally slated for a vote on April 27. Sources indicate that the latest postponement was due to the inability to finalize the definitive text of the document.

The resolution, strongly backed by Western nations, notably Germany, France, and the USA, as well as by the Bosniak Muslim leadership in Bosnia, faces opposition from Bosnian Serbs and Serbia, supported by Russia and China. They perceive it as an endeavour to collectively assign blame to Serbs for what they view as a grave war crime rather than genocide.

If approved by the General Assembly, “Bosnia might not survive,” the president of the Serbian entity of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the nationalist and pro-Russian leader Milorad Dodik, warned, evoking a ‘semi-secession’ if the resolution will be passed in New York. Meanwhile, in April, thousands of Serbs marched in protest against the resolution in Banja Luka, the capital of Republika Srpska, just after Bosnian Serb lawmakers adopted a more than controversial report denying that the killings in Srebrenica constituted genocide.

Democracy is deteriorating in the Western Balkans, Freedom House says

Sources: Freedom House

The latest Nations in Transit 2024 report, which analyses the democratic trends in 29 countries in Central Europe to Central Asia, developed by Freedom House, revealed that all Western Balkan countries continue to exhibit characteristics of “hybrid or transitional regimes,” with four experiencing democratic decline and two stagnating. Serbia, in particular, has witnessed the most significant decline among the 29 countries covered, while Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina also saw declines. Albania and Kosovo’s democracy scores remained unchanged from the previous year.

According to Freedom House, Western Balkan countries are still classified as hybrid or transitional regimes, because elections are organised regularly, but democratic institutions are weak and authoritarian elements persist. Serbia, specifically, falls now under the category of “autocratizing hybrids,” where key institutions, like media and courts, are effectively controlled by ruling parties for partisan or personal interests.

The report highlighted concerns about Serbia, where President Vucic’s ruling has allegedly manipulated elections and utilized both public and private media to target opposition members, journalists, and civil society activists. These actions have contributed to a decline in Serbia’s democracy score, dropping from 3,79 to 3,61.

EU - NATO

EU Parliament adopts resolution on the 6 billion Growth Plan

Sources: European Western Balkans, European Commission

The European Parliament has approved a draft legislative resolution for the establishment of the Reform and Growth Facility for the Western Balkans, also known as the ‘Growth Plan’ (see interview), proposed by President Ursula von der Leyen. The Facility, with €6 billion allocated for 2024-2027, provides €2 billion in non-repayable support and €4 billion in concessional loans. Preconditions include upholding democratic mechanisms, ensuring media freedom, and aligning with the EU’s foreign policy, including measures against Russia. “Enlargement is a key geostrategic priority.

We want to bring the Western Balkans closer and faster to our Union. The €6 billion Facility agreed is a key step in that direction. By combining increased financial assistance and reforms, it will accelerate the progress of our Western Balkan partners on their EU path in advance of accession, foster their economic convergence and integrate them better in our Single Market,” said the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen.

ECONOMICS

World Bank forecasts faster growth in the Balkans

Sources: Reuters, World Bank

A World Bank’s report on the six Western Balkan countries forecasts economic growth of 3,2% in 2024 and 3,5% in the region in 2025, returning to pre-pandemic levels but still insufficient for rapid convergence with the EU. Growth in 2023 slowed to 2,6% due to weakened EU economies, a key trading partner. The report anticipates a 0,2% increase in 2024 growth, attributing this to cautious optimism amid post-pandemic recovery.

However, it warns of risks such as weak investment, geopolitical tensions, migration, electoral uncertainty, and persistent inflation, though inflation rates dropped significantly from 14,3% in January 2023 to 5,1% in December 2023. There are variations in inflation rates across countries, ranging from 2,2% in Bosnia and Herzegovina to 7,6% in Serbia. With GDP per capita at around 40% of the EU average, the region must undertake reforms to narrow the development gap with the EU faster, the World Bank recalled.

Stefano Giantin

Journalist based in the Balkans since 2005, he covers Central- and Eastern Europe for a wide range of media outlets, including the Italian national news agency ANSA, and the dailies La Stampa and Il Piccolo.