Are China-Russia relations still “limitless,” as Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin declared on the 4th of February this year? Probably not, or instead, they were not even before. While the countries back each other on many international dossiers and stage joint military drills, they were not and are not formal allies.

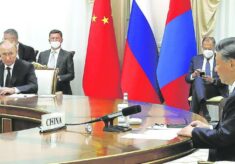

In the last meeting between the two leaders, Putin promised to address the “questions and concerns” that China has about the Ukraine war. Coldness and detachment, on the other hand, are the two posturing elements of the Chinese coming out of that face-to-face in Samarkand – where the two were to take part in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit.

For Xi, the multilateral value of that context was much more important than the meeting with Putin. The SCO, a Chinese idea, is a growing organization (the importance of Iran’s inclusion is a case in point) with more than 40% of the world’s population and more than 30% of the global GDP.

SCO has the strength to be one of the multilateral centres where China can develop its multipolar model, de jure et de facto alternative to the West. Beijing wants and needs Russia at his side, but does not up to the point of jeopardising wider interests. So, it is no accident that Xi stressed concepts such as sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity during bilateral talks with Central Asian countries leaders (the opposite of what Putin does in Ukraine).

Central Asia is emblematic of how the interests of China and Russia are overlapping (and when the overlap concerns areas of influence does not usually have a positive consequences). China needs to keep a double track with the Russian issue.

On the one hand, Beijing has to continue the relationship (not least because the Chinese are taking advantage of Western sanctions related to the Russian invasion of Ukraine to buy oil from Moscow at $25/barrel markdowns). And that is why Xi Jinping does not condemn Putin’s war, relegating it to issues on which to apply the principle of non-interference (although later it may be more important for him to catch up with Kyiv).

On the other, China wants to avoid perceptions of close association with Russia. At home and abroad, China likes to stress his desire for stability, while Putin’s is the opposite; unfortunately, the clashes in Caucasus and Central Asia were perceived as ripples of the Ukrainian war even if their causes were eminently local. And the recent setback makes for the moment the “special military operation” an example of military adventurism, something that has a negative connotation in Communist political jargon. For Beijing, face is paramount because it is strategically important even more in these weeks before China Communist Party’s Congress (on 16 October).

In essence, the relationship between China and Russia is standing and strong, but firstly asymmetrical (China has a major role), secondly utilitarian vis-à-vis the USA and thirdly nuanced by mutual uncertainty and misgivings. Russia and China have aligned because their world views have much in common. Russia is a useful partner, but not if it is to cause weakness and embarrassment for China.

Emanuele Rossi

He is an author and is specialised in international affairs and geopolitics with a focus on transatlantic relations, USA, China, Middle East.