Archive

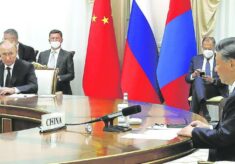

Xi-Putin: friendship, partnership, interest(ship)?

26 September 2022

A global long-term China-US crisis is unfolding

4 August 2022

The Madrid Summit and the Seoul-Tokyo connection

4 July 2022

Australia re-pivots to a core Indo-Pacific

29 July 2020

Australia and India converge over the Indo-Pacific

27 June 2020

Covid-19 disruption across the Indo-Pacific

23 April 2020

Germany steps into the Indo-Pacific

28 March 2020

The India-Australia-Indonesia “minilateral”

28 February 2020

China’s demographic challenge

26 February 2020