Archive

The new Mecca of neutralism

13 March 2025

Certain shards, uncertain reconciliations

30 January 2025

Trouble in paradise

16 January 2025

Iran-Russia: towards mutual dependence?

27 November 2024

The race for AI

26 November 2024

KSA and the top brass reshuffle

17 September 2024

Two steps closer to the brink

26 August 2024

A red naval exercise in the Gulf of Oman

23 July 2024

Death by heat

12 July 2024

Successions

18 June 2024

Corridors of power

21 May 2024

A geopolitical shield for the EU

8 March 2024

The Red Sea chess game

14 February 2024

COP28: UAE leading a complex consensus

12 January 2024

Iraq: maximum pressure, reversed

2 December 2023

Out from the shadows, driven by co-petition

25 October 2023

The limits of minilateralism

19 September 2023

A nuclear-prone ménage à trois

28 August 2023

A charm offensive in Africa

31 July 2023

Caught in a trilemma

30 June 2023

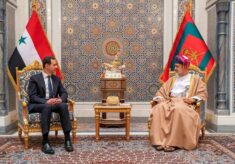

Pariahs no more

30 May 2023

The AI and drone new frontier

27 April 2023

The great reshuffle

11 April 2023

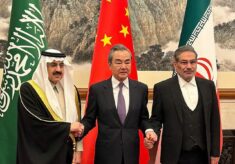

In from the cold

15 March 2023

Moving towards a nuclear Middle East

9 February 2023

A multipolar order in the making?

4 January 2023