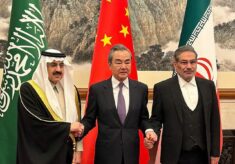

The end of the year in the Gulf region was evidently marked by the high-profile visit of Chinese President Xi Jinping to Saudi Arabia which, alongside consolidating relations between important trade partners, also gave a glimpse of what the post-American Middle East could look like. Leaving mainland in China, where widespread protests against the zero-COVID policy adopted by Beijing were undermining the uncontested rule of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) before being reversed; and just after securing an unprecedented third term in office, on the 7th of December Xi landed in Riyadh for a three-day visit that drew immense scrutiny not only in Washington but also on the other bank of the Gulf.