As soon as leaving the Nikola Tesla airport in Belgrade, people inevitably step into an immense Soviet-era skyscraper serving as gateway to the city. Having become dear to influencers from all over the world due to its characterization as an example of the famous “Soviet brutalism” architecture, the Genex Tower (completed in 1980) hosts a bed&breakfast which – due to its popularity among young travellers – has a months-long waiting list. Next to the 35-floors building, what catches the eye is a handwriting probably made with a spray can: “Kosovo is Serbia”. Breaking into similar scripts on the walls of underpasses, on viaducts’ pylons and even on banners located next to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is not uncommon in Belgrade. A phenomenon that clearly signals the presence of still open historical issues, as well as of wounds that in Serbia are not completely healed.

Against this background, the military presence of NATO in the Balkan region is extraordinarily required in order to maintain stability and bring peace to the area. What is more, it apparently serves as a balancing factor to the (geo)political, economic and strategic advancement of revisionist powers aiming at extending their spheres of influence to include Balkan countries at the detriment of the “West”. This proves to be even more relevant within an international environment rapidly leaning towards multipolarity, in which political realism vehemently makes its return as the underlying force behind great powers’ global stance.

In spite of the voluntarily unaltered visible signs of NATO intervention in March-June 1999 (i.e. bombed buildings), Serbia has started to dialogue and to steadily develop cooperation with the Alliance since 2006, when Belgrade joined the Partnership for Peace (PfP) programme and the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC). As a consequence, in December 2006 the NATO Military Liaison Office was established in Belgrade, with a view to support defence reforms in the country; enhance Serbian participation in Partnership for Peace activities; and to assist NATO’s public diplomacy activities in the region. In particular, in 2007 Serbia became part of the Planning and Review Process (PARP) centred upon the development of capacity building among local forces, so as to be able to partake into UN-mandated multinational operations and EU crisis management activities. Similarly, PARP further served as a planning tool to measure progress in defence and military transformation.

Beyond that, NATO actively engaged in Building Integrity (BI) actions to strengthen integrity, accountability and transparency in Serbia, as well as to reduce corruption in the defence and security sector. The Defence Education Enhancement Programme, supporting the development of Serbia’s modern defence education system, the Partnership Interoperability Initiative and the provision of training courses within the NATO Defence and Related Security Capacity Building Initiative represent further cases in point of a growing cooperation between Belgrade and the Alliance.

Within the framework of a wider cooperation scheme, several other initiatives deserve to be mentioned. As a matter of fact, in 2003 the destruction of 28.000 surplus small arms and light weapons was completed thanks to the NATO Trust Fund project in Serbia. Besides, 1,4 million landmines and ammunition were safely cleared in 2007, with approximately 8.000 tons of surplus explosives still in the process of destruction.

As far as concerns additional military-related areas of cooperation, Serbia and NATO closely cooperate in the field of counter-terrorism, energy security, advanced technology, border security, human security and mine and unexploded ordnance clearance. Indeed, Belgrade is actively developing its national civil preparedness and disaster management capabilities, as well as improving interoperability in international disaster response operations.

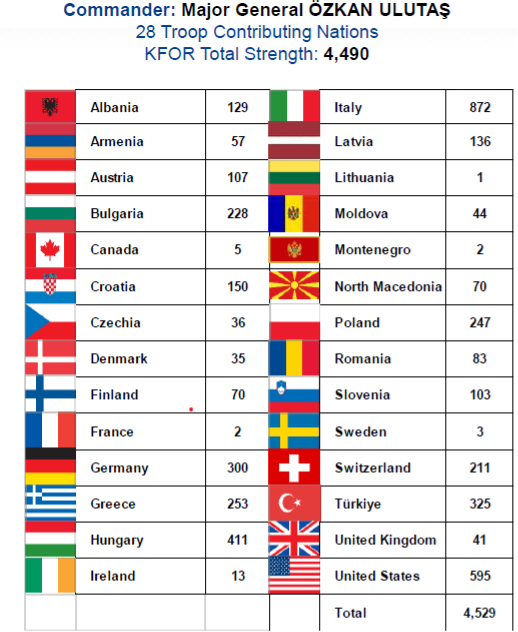

Nonetheless, by taking into account the presence of a tangible Serbian nationalism and the wider significance of NATO presence in the Balkans, it must be acknowledged that the Alliance still remains a key subject for the fostering of dialogue and the provision of a safe and secure environment in Kosovo. On the basis of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244 and of the 1999 Military Technical Agreement, Serbian Armed Forces have cooperated with KFOR during several years, and especially through the Joint Implementation Council. Despite NATO’s uninterrupted support (the best example of NATO/EU collaboration), however, the facilitation of dialogue with the European Union and between Belgrade and Pristina has not yet brought to any tangible prospect of normalization. On the contrary, since the election of Albin Kurti as Prime Minister of Kosovo, tensions with Serbian residents of Northern Kosovo erupted with an increasing frequency, thereby causing additional fractures with the political élite of Serbia.

From a geopolitical perspective, it should be noted that the unconditional support of Kosovo from NATO-Member Türkiye and the presence of its military forces among the ranks of KFOR may hinder the smooth relations with Serbia. Hence, in addition to its participation to NATO’s operations in the Balkans, it is a well-known fact that President Erdoğan’s Türkiye is pursuing a national strategy of pan-Turanism having as ultimate purpose the extension of the country’s sphere of influence from the Mediterranean to the Middle East and to Central Asia, passing through the South Caucasus and possibly the Black Sea. The Balkans make no exception in Erdoğan’s stance: indeed, besides ethnical and religious affinity with numerous communities residing in the Balkan region (Albania, Kosovo, Muslim communities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, among others), Türkiye is particularly interested in carving out a role for itself in the area with a view to control the energy and infrastructure routes that lead from Central Asia and the Caucasus to Europe, thus contributing to its energy diversification strategy (and ultimately security). Even more important, thanks to its strategic projection in the Balkans, Türkiye is involuntarily promoting the alignment of numerous countries to NATO’s standards and equipment through the export of its Bayraktar TB2 drones, most of the times by selling military systems at a convenient price, depending on the buyer.

Despite this, in the military sphere the strongest competition with the other great powers that Türkiye (and therefore NATO) has to face occurs once again in Serbia. Regardless of its Slavic-orthodox heritage and the traditional sympathy for Putin’s Russian Federation (which recently emerged in President Vučić refusal to align with Western sanctions to the Kremlin following the invasion of Ukraine), at the end of January Belgrade suspended a set of contracts with Moscow for the supply of military equipment. This event, however, heavily benefited China, which immediately entered into multiple military agreements with the country. The result is Serbia being the only non-NATO country in the wider European continent in possession of the prestigious Chinese HQ-22 (FK-3) long-range air defense system (170 km engagement range). Considering the current internal tensions in Serbia, the mass protests and the eventual political crisis spurred by the Novi Sad train station incident (a Beijing-financed project), the granting of military contracts and the increased geoeconomic cooperation among the two countries represents undoubtedly a factor of instability in the region, as well as an aspect that NATO must not underestimate.

With the European Union currently engaged on the Ukrainian front, which seems to have put on hold the integration process of the Western Balkans and in particular the accession of Serbia, NATO remains the key player for the stability of the region, as well as for the maintenance of a strong Western influence at the expense of the attempts of revisionist powers.

Valentina Chabert

Ms Chabert is a Ph.D. Candidate in International Law, Sapienza University of Rome and member of the Board of Advisors of The Hague Research Institute.