South East Asia has always been considered peripheral by transnational jihadist organizations, a region that has strong and influential tribal dynamics, largely outside of the influence of the central government.

Clan-based social structures in the Philippines have been infiltrated by jihadist organizations, but the latter are in turn heavily dependent on the former for recruitment and operational planning. Terrorism influences the geographic, socio-cultural and economic spaces and it is in turn influenced by them.

Clan-based social structures in the Philippines have been infiltrated by jihadist organizations, but the latter are in turn heavily dependent on the former for recruitment and operational planning. Terrorism influences the geographic, socio-cultural and economic spaces and it is in turn influenced by them.

Several militant factions that answered the Islamic State’s call were already present in the armed struggle in the Philippines but rebranded themselves from “nationalist-separatists” to “jihadists”, often, at least initially, in order to obtain additional funding from Middle Eastern sponsors. So, the ideological credentials of these new jihadis are weak compared to well-established groups and opportunism can be stronger than ideological affiliation.

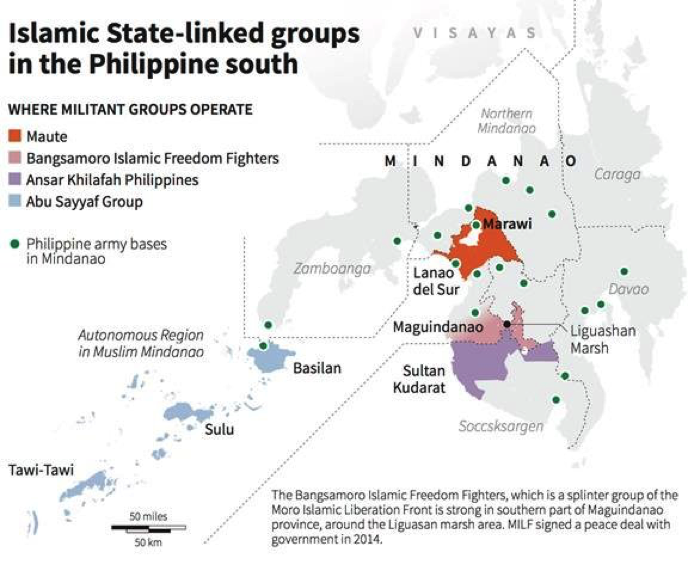

In fact, the conquest of Marawi City by the Islamic State, which then led to a lengthy and bloody battle with the Armed Forces of the Philippines in 2017, was not only due to IS military prowess, but to the conjunction of terrorism with the illegal economy, as the city, even before the capture, was viewed as a stronghold of clans involved in organized crime. In Marawi, jihadism was able to insert itself in the cultural and the (illegal) economic spaces to gain a territorial foothold and helped Islamic State score a major propaganda victory.

The adoption of suicide terrorism in the Philippines, started in June 2019, was initially considered a sign of Middle Eastern jihadist influence. In reality, this tactic is not alien in the Filipino context. Moro Muslim tribes in present day’s Philippines and Indonesia are known to have waged parang sabil against the Western colonial forces almost two centuries ago.

Parang sabil is often translated as “war in the path of God” and its rise might be attributed to the 1876 establishment of a Spanish garrison in Jolo, Sulu. The Spanish colonisers were in a decades-long war with the Sultanate of Sulu, but when the sultanate showed its weakness, the struggle became fragmented in little groups till the level of a single fighter.

In addition to surprise raids against enemy troops and local auxiliaries, parang sabil was developed as dispersed static defensive tactic to bleed the occupants. Similar to the resistance of the Masada fortress by the sicarii (Jewish War, 66–73 AD) on a very small scale, groups of fighters would set up small forts, preparing themselves to a suicidal resistance after a ceremony and a solemn oath. It might well be that jihadist organizations have exploited this feature of the sociocultural space with new techniques and weapons.

An interesting feature of the geographical space in South East Asia is that it has both a land and a maritime dimension. Jihadist groups thrive in ungoverned spaces, where they can replace the central government. This is true for both the vast mangrove forests and the Celebes and Sulu seas, where the distinction between terrorism and maritime piracy has become blurred.

Kidnappings orchestrated by Jemaah Islamiyah in the jungles of Indonesia or by Abu Sayyaf in the Sulu Sea mirrors the kidnappings orchestrated by AQIM in the Sahel: they are used to accumulate a relatively easy (since the targets are civilian) profit in the short term that is then reinvested locally, in order to gain clout within the communities in the long term. Moreover, in both continents, jihadist groups are able to exploit the remoteness of the location, as well as extremely porous borders, to conduct criminal activities and easily evade security forces.

The most recent reports of the United Nation’s Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team also highlights that kidnapping for ransom remains an important source of revenue for terrorist groups in West Africa as well. In these African regions and South East Asia there are strong links between local criminal networks and terrorist groups, which mutually benefit both actors.

Weapon smuggling is inherently a very lucrative transnational activity for the tribes controlling it; but of course, it has the potential to exacerbate violence at the local level. In South East Asia, weapon smugglers are able to take advantage of the Celebes and Sulu Seas to move weapons from the Philippines (the major source of illicit weapons in the area) to even the most remote areas of Indonesia, where terrorist groups operate. These groups can also benefit by inserting themselves in this trade and become important players in weapon smuggling routes, employing locals as smugglers or by taxing them at key nodes.

Terrorists can become local employers, manage the illegal economy of the area and forge bonds with the local community, including through marriage. Something similar can also be observed in relation to drug smuggling, an endemic activity that affects South East Asia.

It is therefore paramount to engage with local issues first, in order to gradually loosen the grip of these terrorist organizations in the native communities. Economic-support initiatives spearheaded by the international community are vital, not only to dissuade people from joining criminal or terrorist organizations by providing income and social services to local communities at the political peripheries of the target countries. They can also help in deradicalization strategies, which have to be implemented according to a whole-of-government approach, as stressed by the United Nations in some of its most recent resolutions. It is easy to see that this systemic approach takes into account similarities already observed in the Sahel and West Africa and needs similar means.

Francesco Conti

Research Assistant at the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT), Reichman University, Herzlya.