As Jean Monnet said, “Europe will be forged in crises and will be the sum of the solutions adopted for these crises“, and, once again, Europe and NATO will have to face a new season of crises, that has aptly been described as a permacrisis. Let us first quickly draw a global macroeconomic picture based on the IMF’s forecasts. We know the economy can be fallible in forecasting, but when the going gets tough, it’s best to be cautious.

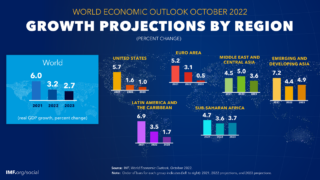

These three graphics are quite useful to summarise the situation.

In the 2022 World Economic Outlook the conclusions are quite clear:

“Policy paths in the largest economies could continue to diverge, leading to further US dollar appreciation and cross-border tensions. More energy and food price shocks might cause inflation to persist for longer. Global tightening in financing conditions could trigger widespread emerging market debt distress. Halting gas supplies by Russia could depress output in Europe. A resurgence of COVID-19 or new global health scares might further stunt growth. A worsening of China’s property sector crisis could spill over to the domestic banking sector and weigh heavily on the country’s growth, with negative cross-border effects. And geopolitical fragmentation could impede trade and capital flows, further hindering climate policy cooperation”.

All this means that, even managing to avoid another global crisis (the third after that of 2006 and the pandemic), the combination of stymied growth, monetary rigour, inflation and other geopolitical factors already mentioned, would drastically reduce financial resources not only for a possible Ukrainian reconstruction plan, but for that defence expenditure which is objectively necessary.

In this already difficult picture, it is important to draw the attention on some few important factors in the expected arms procurement, if we are to ensure credible deterrence:

All EU (and NATO) countries have an urgent need to replenish previous military donations and to massively increase ammunition stockpiles, because we have seen how much ammunition has been consumed in this conflict. Rough Russian estimates speak of 3,6 million 152 mm shells fired in five months, for example;

The 2% criterion regarding the Defense expenditure/GDP ratio has always been an indicative criterion: now what matters is the purchase of concrete capabilities, i.e., weapon systems useful for the defence of NATO and national territory, with an effective logistic supply of spare parts and ammunition, as well as with a concrete availability of trained personnel: we have seen that an army of 100.000 fighters lasts for about eight months of medium intensity operations;

Even by increasing defence funds, a recurring phenomenon in all European armed forces, with some rare exceptions, consists in still financing weapon systems that were suitable for managing crises, possibly overseas, avoiding the reconstitution of that heavy or high fire potential that is necessary in deterrence and/or defence;

Those European countries that have disposed of Soviet systems to supply Ukrainian forces are typically markets already captured by non-EU, and sometimes not even NATO suppliers, who have the advantage of lower unitary prices.

Here, the word unitary price is key to understanding what the concrete needs of governments and defence industries are when tackling the challenge of new responsibilities that are already emerging in the bilateral arena with the United States and with NATO: the so-called European pillar is not more a simple desirable option, but a necessity arising from tensions in the Indo-Pacific (which will absorb more and more US forces deployed in Europe) and from the simple observation that EU and non-EU countries in the continent are spending four times the Russian military budget and must guarantee a much more effective defence than the Ukrainian one, made essentially on a budget: 5,9 billion current dollars against, for example, the 36 billion of the Italian military budget, (i.e., is one sixth).

The public has certainly heard about the European army and strategic autonomy, objectives that are commendable in themselves and do not affect transatlantic bonds, but after 30 years of ambitious intentions and proclamations, it is time to come down to earth, exactly to achieve them.

This requires avoiding the “hexagonal” temptations to travel alone, a thing that has proven its limits once combat tested during the Iraqi campaign. Europe can and must develop capabilities and therefore effective units and weapon systems, using the NATO system as an incubator rather than reinventing the wheel. This does not mean a standardization around the leading nation, something that happened only in the Warsaw Pact, but it means creating a viable European defence market within the reach of the financial needs of governments due to sizeable production numbers. This is also the only way to have a satisfying two-way street across the Atlantic.

And since we know that in developing highly complex systems it is very difficult (although not impossible) to agree, we also know that true standardization is much easier in land forces, which are on the first line to guarantee defence and deterrence. In other words it is possible to rationalize the industrial base starting from the bottom, exactly as we have done with strategic assets such as steel and for many other civilian goods of the utmost importance.

In short, we need capabilities, smaller unitary costs, proven incubators, bottom-up standardization and a single market if we want: two-way street, a mature transatlantic link, autonomy and, in perspective, “European” forces.

Alessandro Politi

Director of the NATO Defense College Foundation