Libya: a multi-layer conflict

Umberto Profazio

A decade after the Benghazi uprisings that sparked the revolution, Libya’s future remains largely unwritten. The transition from the oppressive dictatorship of Muammar Gadhafi to a democratic form of government in which Libyans would enjoy and upheld principles for which they fought in 2011, such as legitimacy, representativeness and rule of law, seems suspended halfway between the dangerous brinkmanship of the latest round of fighting and the opaqueness of a political system that is attempting to reinvent itself, after coming under increasing pressure from the popular mobilisation of the Libyan Hirak.

The momentum, provided by a military stalemate that resulted from the 2019-2020 year of living dangerously and new international dynamics stemming from the change of administration in the USA, is offering Libya an unmissable chance to end the civil war and complete the transition process. The October 2020 ceasefire agreement brokered by the United Nations Support Mission in Libya certainly represented a turning point, triggering a political process resulting in the establishment of a new executive authority expected to bring the country to elections on the 24th of December 2021, Libya’s Independence day. Nevertheless, the persisting presence of foreign forces, mercenaries and private military contractors on both sides of the Sirte-Jufra frontline raises serious questions about the extent of Libya’s real independence, while unveiling the multiple layers of the conflict at the same time.

On a domestic level, a new Government of National Unity headed by Prime Minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibah and a reformed Presidency Council led by Mohamed al-Menfi replaced the discredited and delegitimised political institutions in the east and the west, reverting a fragmentation process ongoing since 2011. However, a complete turnover of the political elite remains elusive and the confidence vote given by the House of Representatives to the new government epitomised a peculiar cohabitation between the emerging leadership and ‘political dinosaurs’ that spells trouble for Libya’s incomplete transition. More in general, political heavyweights that remained excluded from the UN-sponsored political process are keeping an eye on the December 24 deadline to get back in the game. As the old and new forces pull on opposite sides, the risk of overstretching an already polarised political landscape increases, providing a wide range of marginalised actors with an opportunity to spoil the political roadmap adopted by the Libyan Political Dialogue Forum.

In this context, the controversial figure of Field Marshall Khalifa Haftar remains central to understand which direction the Libyan peace process would take in the coming months. Despite his unsuccessful attempt to take control of Tripoli, Haftar is still in control of the main terminals in the oil crescent region and the main oilfields in the south. Furthermore, holding on his leadership of the Libyan National Army gives the General a substantial say on any attempt to reunify the military institutions, which remain divided between the East and the West; and fragmented, due to the proliferation of militias and armed groups throughout the country. In essence, control of the oil resources and the military leadership gives Haftar a considerable sway over the peace process, while at the same time highlighting two of the major obstacles still preventing any successful transition. Questions around the distribution of the oil revenues and the establishment of a unified Libyan military will continue to revolve, considering the priority given to the elections over the accomplishment of the constitutional process, without which the Libyan peace process will remain incomplete.

Being halfway in consolidating its institutional architecture, Libya risks being unable to resist foreign interferences, becoming prey of the great power competition in which assertive regional players are also playing a prominent role. Despite the gradual shift from the excesses of the power politics that has characterised the recent escalation to the intense international competition for the reconstruction of the conflict-thorn country, foreign meddlers still dispose of considerable clout.

In particular, Russia and Turkey have emerged as the main powerbrokers, being able to expand their diplomatic influence and establishing a military foothold often resorting to a successful hybrid playbook. In this context, negotiations and talks in UN-sponsored forum could well represent a “veil of Maya” behind which Ankara and Moscow are still jockeying to reap the benefits of their latest interventions in the Libyan conflict. Divided by a trench and fortifications along the Sirte-Jufra frontline, Russian and Turkish forces, military contractors and mercenaries are still poised to shatter the illusion of a political solution or could simply maintain the conflict frozen while waiting for more favourable conditions to settle their old scores.

Umberto Profazio

Associate Fellow for the Conflict, Security and Development Programme at the IISS and Maghreb Analyst for the NATO Defense College Foundation, he regularly publishes on issues such as political developments, security and terrorism in the North Africa region, focusing on the conflict in Libya, the politics and geopolitics of the Maghreb and the role of non-state actors. He holds a PhD in history of international relations from the University of Rome (Sapienza), with a thesis on Libya after independence.

Other articles

Foreword

Alessandro Minuto-Rizzo

Political Summary

Alessandro Politi

Policy Paper

Arab rising and beyond

Claire Spencer

The economy and the civil society

Possible roots of the rising

Abdulaziz Sager

What kind of economic prospects for the region?

Karim El Aynaoui, Oumayma Bourhriba

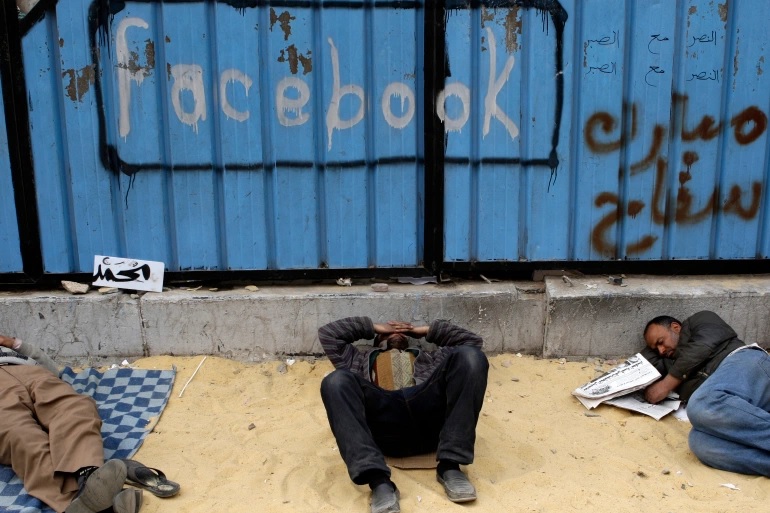

From the web to the square

Mahboub E. Hasem

Power and identity

10 Years After the Arab Spring: llicit Economies Evolve, Epand and Entrench

Matt Herbert

Libya: a multi-layer conflict

Umberto Profazio

The Egyptian long pacification

Eman Ragab

A new wave of unrest: towards change?

Future perspectives in the Gulf

Jean-Loup Saman

The way ahead

A look the the future

Ahmad Masa’deh

The Alliance looks South

Appendix

The Arab rising by country

Mahboub E. Hashem