Future perspectives in the Gulf

Jean-Loup Samaan

Ten years after the revolutions that shook the Arab world, the monarchies of the Gulf Cooperation (GCC) face a series of tremendous security and economic challenges. These may not put into question the nature of their political systems, but they definitely test the ability of local leaders to address them.

First, Gulf states face the fallouts of the Covid-19 crisis. They generally fared better than Western countries vis-a-vis the pandemic (on daily cases or deaths per capita) but they have not been immune to the economic consequences.

The health situation exacerbated the fall of oil prices that started with the 2014 market crisis. The sudden halt of global demand and the Saudi-Russian battle in Spring 2020 over production levels inflicted a major blow to the market. This situation directly impacted Gulf rentier states that generally need a 70$ barrel to break even with their public expenditures. Consequently, sovereign debt in the region has been on the rise. In Bahrain and Oman, it is forcing local governments to rely more and more on foreign aid. But the economic fallout of the pandemic is also painful for those that had already diversified their source of revenues: Dubai whose wealth relies primarily less on energy than on being a regional hub for finance, tourism, maritime and air traffic was badly hit as well.

The long-term effects of the pandemic also have ramifications on the social fabric in the GCC countries. In Kuwait, it exacerbated xenophobic sentiments used by parliamentarians seeing the foreign labour force as a convenient scapegoat for the virus proliferation. In other states, like Oman and Bahrain, the economic crisis complicates the ability of local rulers to implement the much-needed socio-economic reforms to assuage potential discontent that existed prior to 2020.

Meanwhile, the war in Yemen, now in its sixth year, remains a major threat to regional stability. Sadly, there is no end in sight: the coalition assembled by Riyadh has been unable to succeed militarily against the Houthi rebels and the prolonged fighting created one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world. Well aware of the reputational cost the conflict has inflicted on Saudi Arabia, its leadership displayed a willingness to negotiate a diplomatic settlement in early 2021 but the Houthis dismissed the initiative as they seemingly believe to be on the winning side of the war.

Beyond the war in Yemen, regional stability is still defined by the evolving competition between Saudi Arabia and Iran. The regional strategy of the latter maintains a high level of assertiveness, be it through its variable support of proxy militias in the region or its campaign of naval harassment in the strait of Hormuz. Furthermore, Iran’s nuclear programme remains a major issue for Gulf states. Back in 2018, the US withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) provided Tehran with a convenient pretext to progressively reduce its own commitments with the initial deal, in particular regarding the level of uranium enrichment.

The fate of the Iranian nuclear issue will also test the relationship between GCC states and the new US administration led by President Joe Biden. As many members of the current national security team in Washington already worked under the Obama presidency, rulers in Saudi Arabia and the UAE have not hidden their concerns. Back in 2015, Gulf states had only reluctantly endorsed the JCPOA, feeling that they had not been consulted and that their national security interests were undermined by the deal. The fact that the Biden administration declared its intention to resume talks with Iran while removing the Houthis from the list of terrorist organizations and at the same time, suspending its arms sales to both Saudi Arabia and the UAE obviously sent a negative message in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi. However, this is unlikely to compromise the presence of US armed forces in the Arabian Peninsula, which still makes the US the most decisive military player in the Gulf.

Still, US-Gulf relations will increasingly be tested by the implications of the rapprochement between GCC states and China. Over the past five years, this cooperation with Beijing diversified and increased. Initially driven by China’s consumption of Gulf oil, these partnerships now include Chinese investments into Gulf ports infrastructures (in Abu Dhabi’s Khalifa Port, Oman’s Duqm Port as well as the Hamad Port in Qatar), Huawei’s management of the 5G networks in the Peninsula (for instance in Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the UAE) and limited but significant arms sales (such as drones and short-range ballistic missiles).

But as the US-China competition escalates, it becomes one (rare) topic of bipartisan consensus in Washington where politicians see the rivalry turning into a zero-sum game and forcing allies of the US to make one single choice. As a result, American officials are likely to increase their pressure on Gulf states to carefully reconsider their rapprochement with China if they want to keep benefiting from the US security umbrella.

All in all, Gulf states may have been able to cope with the regional turmoil that ensued from the 2011 revolutions, but they do face a wide array of critical challenges that will definitely test their resilience for the next decade.

Jean-Loup Samaan

Dr Samaan is a research affiliate with the Middle East Institute at the National University of Singapore. He worked in various positions for the French Ministry of Defense, NATO and the RAND Corporation. His research focuses on Israel-Hezbollah conflict, and the evolving Gulf security system. He authored 4 books and several peer-reviewed articles. He holds a Ph.D. in political science from the University of Paris, La Sorbonne as well as an accreditation to supervise research from Sciences Po, Paris.

Other articles

Foreword

Alessandro Minuto-Rizzo

Political Summary

Alessandro Politi

Policy Paper

Arab rising and beyond

Claire Spencer

The economy and the civil society

Possible roots of the rising

Abdulaziz Sager

What kind of economic prospects for the region?

Karim El Aynaoui, Oumayma Bourhriba

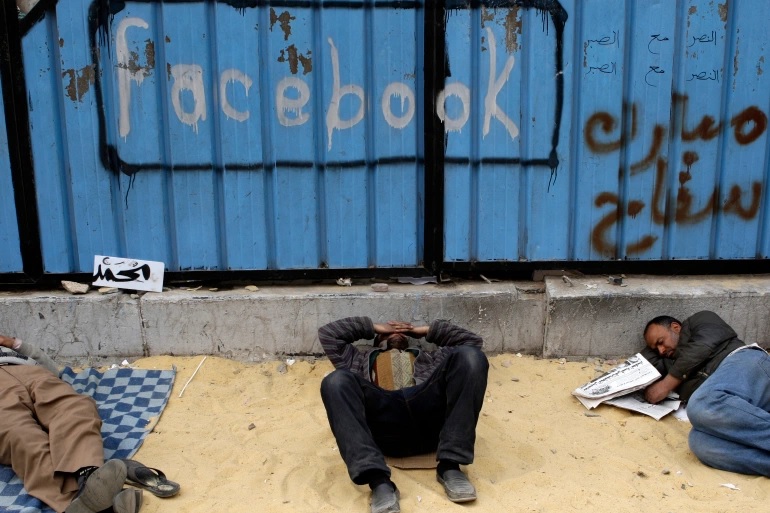

From the web to the square

Mahboub E. Hasem

Power and identity

10 Years After the Arab Spring: llicit Economies Evolve, Epand and Entrench

Matt Herbert

Libya: a multi-layer conflict

Umberto Profazio

The Egyptian long pacification

Eman Ragab

A new wave of unrest: towards change?

Future perspectives in the Gulf

Jean-Loup Saman

The way ahead

A look the the future

Ahmad Masa’deh

The Alliance looks South

Appendix

The Arab rising by country

Mahboub E. Hashem