10 Years After the Arab Spring: llicit Economies Evolve, Epand and Entrench

Matt Herbert

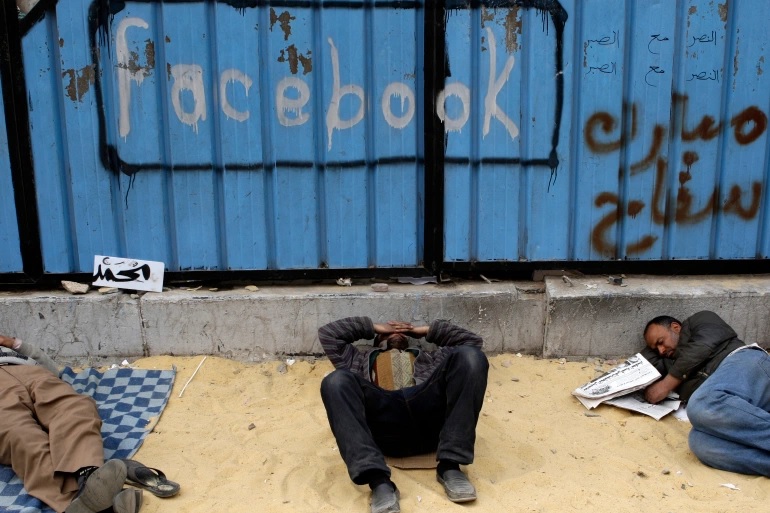

The 2011 Arab uprisings have reverberated over the last decade, continuing to influence the politics and popular expectations on the relationship between government and those governed throughout in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). However, they have also contributed to conflicts in Syria, Libya and Yemen and an increased fragility amongst many states within the region, and in peripheral areas such as the Sahel, and economic challenges for large swaths of the population in MENA states(1).

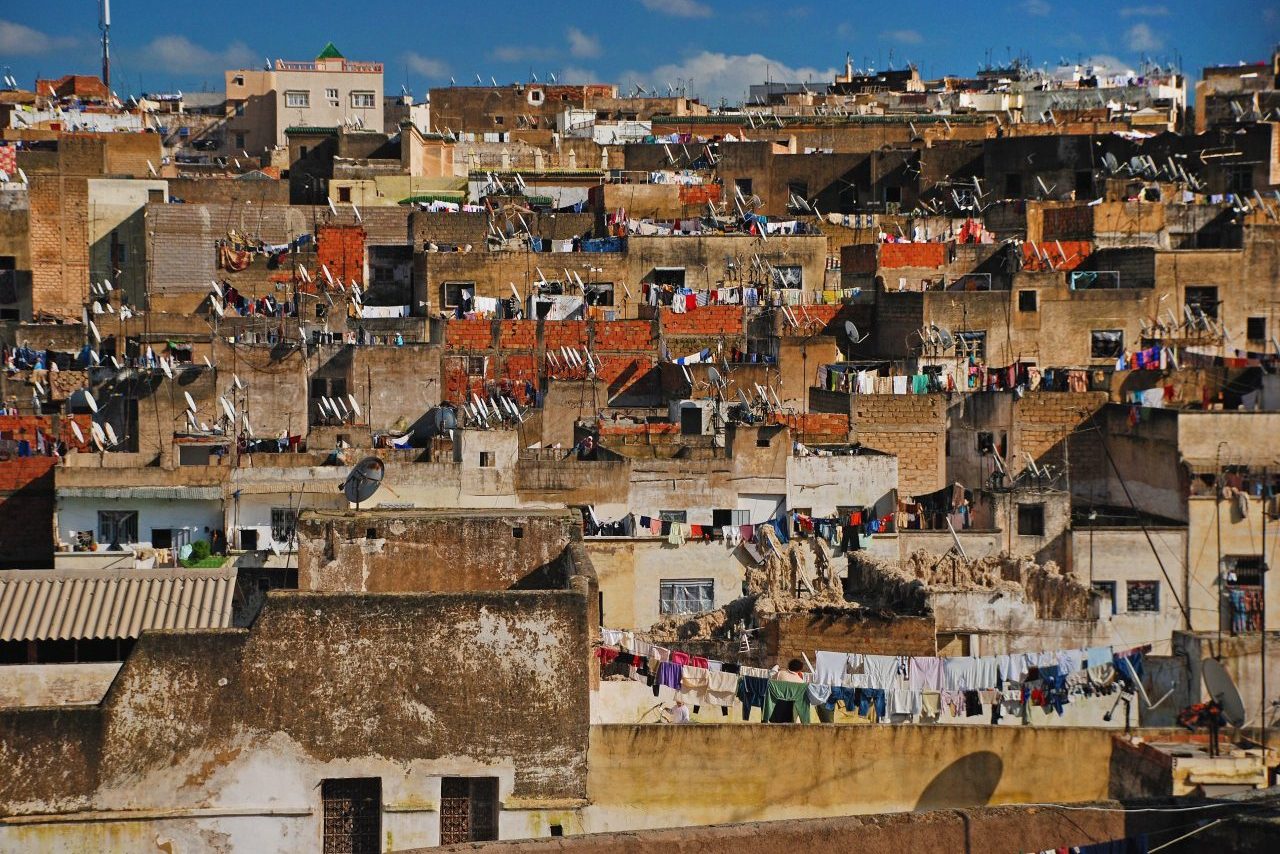

The events of 2011 have also impacted the evolution of transnational organized crime in MENA states. Organized crime and illicit economies, such as drug trafficking and human smuggling, have long existed in the region. Lebanon and Morocco have been key cannabis production points for decades, while human smuggling across the Mediterranean from North Africa to Europe occurred in significant volumes throughout the 1990s and 2000s(2).

However, over the last decade these illicit economies and others have evolved, expanded and entrenched, with interlinkages between criminal actors and formal power structures deepening, leading to organized crime groups that are more robust and capable of posing far greater challenges to regional states in 2021 than what had existed a decade before.

Specifically, the events of 2011 uprisings have shaped the evolution of organized crime in four ways. First, changes in demand and in the operating environment have allowed illicit economies in MENA to expand and entrench. The most highly visible example of this involves human smuggling, with networks operating throughout the eastern and southern shores of the Mediterranean expanding dramatically over the last decade, catering to a sharp increase in demand by migrants and refugees, including those displaced by the conflict in Syria, seeking access to Europe(3) . This expansion has further been enabled by conflict and fragility, such as in Libya, which has limited the ability of law enforcement to counter the trade(4) .

As well, expansion of organized crime has been driven by the imposition of embargoes on Syria and Libya. This has driven demand for accessing prohibited goods – notably weapons – and created incentives for governments to tacitly allow the operations of some types of criminal organizations.

Second, there has been a change in the geography of illicit economies in the region, with criminal actors operating more regularly across a far greater swath of space than in the past. Much of the shift in geography is attributable to the conflicts in Syria and Libya, which have created contested space in which organized crime has flourished. The drug trade illustrates this change. While Morocco and Lebanon remain key production points, Syria and Libya have emerged as important zones for production, storage and trafficking of drugs(5) . In Syria, a degradation of law enforcement capacity and limited government focus on drugs have led to its emergence as a key regional node, both for the shipment of cannabis resin and for the production and export of Captagon. The volumes of the latter drug produced in the country are extremely large, with just one shipment, intercepted by Italian authorities in 2020, valued at USD $1,13 billion(6) .

Rather than a production point, post-conflict fragility in Libya has allowed led to its transformation into entrepot state for trafficking, with shipments of cannabis, Captagon and other drugs arriving from Morocco, Lebanon and Syria, before being re-shipped to Europe, Egypt and further afield(7) .

Further, the geography of crime within MENA has also been altered by conflicts in peripheral regions. In particular, rising conflict and instability in the Sahel – in part catalysed by Libya’s 2011 revolution – have become so acute led some drug trafficking networks have begun to actively avoid the region, rather rerouting shipments through areas of North Africa(8) . In particular, South American cocaine traffickers, often abetted by local criminal groups, have started to shift trafficking routes to states such as Morocco and Algeria, and on to Europe, an evolution raises worrisome risks of narcotics linked corruption and instability(9) .

Third, the last decades have witnessed a shift in who is involved in organized crime and illicit economies. In some instances, such as in Tunisia, the number of people involved in smuggling has sharply increased, driven both by economic need and increased opportunity, due to post-2011 weaknesses in border security(10). Mostly, this has involved the transport of pedestrian contraband – such as food or petrol.(11) However, in some instances such petits commerçants have slowly gravitated towards involvement in more illicit forms of organized crime, such as the trade in drugs or arms(12).

In other instances, terrorist groups and militias have become functionally entwinned in illicit markets. In Syria, for much of the mid-2010s, the Islamic State was deeply enmeshed in oil smuggling, as well, to a lesser degree in other forms of criminality, such as drug and antiquities trafficking and human smuggling, leveraging the illicit economies to self-fund its military operations(13). A similar dynamic continues to prevail in Libya, with armed groups throughout the country deeply involved both in the taxation of people smuggling, petrol trafficking and drug trafficking, but also in certain cases directly involved(14). Though not unprecedented – with groups such as Hezbollah linked to illicit economies for decades – like illicit economies more broadly, this entwining has occurred over a larger geographic area than in the past, and risks further challenging the ability of regional states to functionally counter the growth of organized crime.

Finally, in the wake of the 2011 the relationship between organized crime actors and authorities have been altered in many states throughout the region. In North Africa, for example, states historically viewed the challenge posed by criminal actors as limited. Rather, smugglers involved in the movement of contraband commodities, such as petrol or people, were tacitly allowed to operate, as long as they provided intelligence information to authorities and eschewed involvement in drug or arms trafficking, or the provision of assistance to terrorists(15). In this relationship, states exercised clear dominance, relying on functional security forces to mete out punishment on transgressors.

Since 2011, however, law enforcement capacity has declined in a number of states within the region. This degradation, which occurred concurrently with the increase in the scope and power of organized crime groups, and their intertwining with armed groups, has up-ended the previous power balances between states and crime groups. In Libya, individuals implicated in criminal activity have functionally been absorbed into state security apparatuses, blurring the lines between criminals and state agents, and posing stark rule of law challenges(16). Instances of criminal corruption have emerged in several states, most notably Algeria, where a number of high-level officials or their relatives were linked to cocaine trafficking(17).

Most ominously, the engagement between crime and the Syrian state has evolved to the degree that the moniker of ‘narco-state’ has increasingly been applied(18).

The last decade has seen the evolution, expansion and entrenchment of organized crime groups, and illicit economies more broadly, throughout MENA. There is little evidence that this trend will be altered in the coming years. If anything, the COVID-19 pandemic has further impacted the fragility of states in region, driving economic desperation, fuelling efforts to emigrate by both legal and irregular means, and limiting the financial resources available to governments. This perfect storm of conditions risks further fuelling the power and geographic reach of organized crime groups in the region, and in so doing posing an even more acute challenge to states and citizens in the Middle East and North Africa.

1) For example, see: Dina Fakoussa and Laura Lale Kabis-Kechrid, “Tunisia’s Fragile Democracy: Decentralization, Institution-Building and The Development Of Marginalized Regions: Perspectives from the Region and Europe,” German Council on Foreign Relations, December 2018, https://dgap.org/en/research/publications/tunisias-fragile-democracy-decentralization-institution-building-and; Alessia Melcangi and Giuseppe Dentice, “Challenges for Egypt’s fragile stability,” MENA Source, Atlantic Council, 03 July 2019, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/ challenges-for-egypt-s-fragile-stability/; World Bank, “Lebanon Sinking into One of the Most Severe Global Crises Episodes, amidst Deliberate Inaction,” 01 June 2021, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/05/01/ lebanon-sinking-into-one-of-the-most-severe-global-crises-episodes; John Calabrese, “Iraq’s Fragile State in the Time of Covid-19,” Middle East Institute, 08 December 2020, https://www. mei.edu/publications/iraqs-fragile-state-time-covid-19.

2) For example, see: US Drug Enforcement Agency, Quarterly Intelligence Trends, Spring 1975, 39; Matt Herbert and Max Gallien, “A Rising Tide: Trends in Production, Trafficking, and Consumption of Drugs in North Africa,” The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, June 2020; Jonathan Marshall, The Lebanese Connection: Corruption, Civil War, and the International Drug Traffic (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012); Matt Herbert, “‘La Mal Vie’: The Complexity and Politics of Irregular Migration in the Maghreb,” Institute for Security Studies (May 2019).

3) Tuesday Reitano and Mark Micallef, “Breathing space: The impact of the EU-Turkey deal on irregular migration,” Institute for Security studies & the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, ISS Paper 297, November 2016.

4) Mark Micallef, “The Human Conveyor Belt: Trends in human trafficking and smuggling in post-revolution Libya,” The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, March 2017.

5) Matt Herbert and Max Gallien, “The Rising Tide: Trends in production, trafficking and consumption of drugs in North Africa,” The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, May 2020, 6-8; Laura Adal, “Organized Crime in the Levant”, The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, February 2021, 6.

6) Adal, 2021, 7.

7) See Adal, 2021; Herbert and Gallien, 2020

8) Ibid.

9) Jihane Ben Yahia and Raouf Farrah, “Algerian cocaine bust points to alarming trends,” ENACT, 10 December 2018, https://enactafrica.org/enact-observer/algerian-cocaine-bustpoints-to-alarming-trends.

10) See Querine Hanlon and Matt Herbert, “Border Security Challenges in the Grand Maghreb,” U.S. Institute of Peace, May 2015; Matt Herbert, “Partisans, Profiteers, and Criminals: Syria’s Illicit Economy,” The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs (Vol. 38, No. 1, Winter 2014); Adal, 2021.

11) See Moncef Kartas. “On the Edge? Trafficking and Insecurity at the Tunisian–Libyan Border,” SANA Working Paper, Small Arms Survey, December 2013; Dalia Ghanem, “The Smuggler Wore a Veil: Women in Algeria’s Illicit Border Trade,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, September 2020, Sarah Dadouch and Nader Durgham, “Smugglers are partly behind Lebanon’s energy crisis. The army is struggling to stop them,” The Washington Post, 5 July 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/lebanon-economic-energy crisis/2021/07/04/b8367752-d8fe-11eb-8c87-ad6f27918c78_story.html; Hanlon and Herbert, 2015.

12) Matt Herbert and Max Gallien, “Divided they fall – Frontiers, borderlands and stability in North Africa,” The Institute for Security Studies, December 2020

13) Herbert, 2014; Mahmut Cegniz, “How Organized Crime and Terror are linked to Oil Smuggling along Turkey’s Borders,” The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, 2017; Husham Al-Hashimi, “ISIS on the Iraqi-Syrian Border: Thriving Smuggling Networks,” New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy, 16 June 2020, https://newlinesinstitute.org/isis/ isis-on-the-iraqi-syrian-border-thriving-smuggling-networks/.

14) Mark Micallef, Raouf Farrah, and Alexandre Bish, “After the storm: Organized crime across the Sahel-Sahara following upheaval in Libya and Mali.” The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, 2019; Mark Micallef, Matt Herbert, Rupert Horsley, Alex Bish, Alice Fereday, and Peter Tinti, “Conflict, Coping and Covid: Changing human smuggling and trafficking dynamics in North Africa and the Sahel in 2019 and 2020,” The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, (April 2021).

15) Matt Herbert, “States and Smugglers: The Ties that Bind and How they Fray,” in Transnational Organized Crime and Political Actors in the Maghreb and Sahel, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, January 2019; Tuesday Reitano and Mark Shaw, “Libya The Politics of Power, Protection, Identity and Illicit Trade,” United Nations University Centre for Policy Research, Crime-Conflict Nexus Series, No 3, May 2017; Herbert, 2014.

16) Matt Herbert, “Less than the Sum of the Parts: Europe’s Fixation with Libyan Border Security,” Institute for Security Studies, May 2019.

17) Herbert and Gallien, 2020.

18) The Economist, “Pop a pill, save a dictator: Syria has become a narco-state,” 24 July 2021, https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2021/07/19/syria-has-become-a-narco-state; Adam Doyle, “Captagon, trafficking, and the long comedown of the Syrian narco-state,” The New Arab, 5 August 2021, https://english.alaraby.co.uk/analysis/captagon-trafficking-and-syrias-narco-state.

Matt Herbert

Dr Matt Herbert is the Research Manager for the North Africa and Sahel Observatory at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, overseeing teams conducting applied field research on the political economy of crime in the two regions. He specializes in transnational organized crime, border management and security sector reform. Dr Herbert previously consulted throughout North Africa and the Sahel on border and security force capacity building, and in East Africa on informal political economy issues. He has also worked on transborder threats on the U.S.-Mexico border, and served as a policy aide to New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson. He holds a PhD in International Relations from The Fletcher School of Law & Diplomacy, Tufts University, and has authored a number of articles, reports and book chapters on crime, migration, border security, and insurgency issues.

Other articles

Foreword

Alessandro Minuto-Rizzo

Political Summary

Alessandro Politi

Policy Paper

Arab rising and beyond

Claire Spencer

The economy and the civil society

Possible roots of the rising

Abdulaziz Sager

What kind of economic prospects for the region?

Karim El Aynaoui, Oumayma Bourhriba

From the web to the square

Mahboub E. Hasem

Power and identity

10 Years After the Arab Spring: llicit Economies Evolve, Epand and Entrench

Matt Herbert

Libya: a multi-layer conflict

Umberto Profazio

The Egyptian long pacification

Eman Ragab

A new wave of unrest: towards change?

Future perspectives in the Gulf

Jean-Loup Saman

The way ahead

A look the the future

Ahmad Masa’deh

The Alliance looks South

Appendix

The Arab rising by country

Mahboub E. Hashem