In the last two months the European Union was actively engaged to increase its political and economic footprint in Central Asia, attempting to exploit the potential geopolitical vacuum following the Russia-Ukraine war, that heavily damaged Moscow’s relations in the region.

As a matter of fact, post-Soviet countries appear profoundly concerned on Putin’s future ambitions and Russian assertive strategy, pushing them to further diversify foreign policy relations. In this scenario, the EU aims to legitimise itself as a reliable and alternative partner, concretely implementing targets and initiatives included in the (renewed) Strategy for Central Asia released in 2019.

On 27-28 October the EU Council President Charles Michel attended the EU-Central Asian summit in Astana (Kazakhstan), meeting Central Asian presidents (with the exception of Turkmenistan, which sent Deputy Chair of the Cabinet of Ministers) and discussing on the enhancement of cooperation and their “commitment to work together for peace, security, democracy, the rule of law, and sustainable development” (Council of the European Union, Joint press communiqué by Heads of State of Central Asia and the President of the European Council, October 27, 2022).

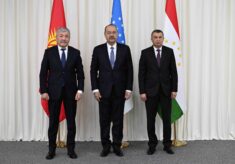

The format of this first high-level Central Asia leaders’ meeting shows how the EU privileges a regional approach in dealing with these republics, that however does not exclude profitable bilateral cooperation in tailored sectors. On the side-lines of the event, Michel also met Kazakh President Tokayev and Uzbek President Mirziyoyev because these countries are clearly recognized as the main partners for the EU to promote regional cooperation, trade relations and political dialogue in Central Asia. Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan are the only two countries that upgraded their relations with the EU, signing the Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement.

On the 17-18th of November, the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs, Josep Borrell, attended the EU-Central Asia Connectivity Conference in Samarkand, presenting the EU as an alternative partner to reduce Sino-Russian influence by supporting projects of regional cooperation, among other initiatives.

During his speech Borrell clarified that “the EU has a lot to offer to help you diversify your foreign policy options” and “support own regional integration efforts” (A. Brzozowski, In Samarkand, EU vies to keep Central Asia close as region walks tightrope between Russia and China, Euractiv, November 18, 2022). This conference was held under the EU’s Global Gateway framework, a €300 billion initiative launched last year to promote sustainable connectivity through investments in infrastructures.

This of course cannot still to compete with the Chinese BRI in terms of trade and infrastructure investment in Central Asia, considering the dimension of the energy and transport projects already financed and realised by Beijing.

The goal of Central Asian countries to diversify foreign policies and to enhance regional cooperation could open a window of opportunity for the EU in the region: the connectivity field appears the most promising field, because the modernization of the transport infrastructures will allow Central Asian states to set aside (similarly to BRI) the Russian-oriented networks of pipelines, roads, and railways. However, the best geopolitical option for the EU will be to progressively become an established partner for these states, lacking for the time being neither economic means nor political tools to openly compete with China and Russia.