Even if border clashes between communities living along the Kyrgyzstan–Tajikistan border have been frequent since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the latest conflict at the end of April appears to be the worst cross-border military conflict in independent Central Asia. As a matter of fact, in three days the conflict has suddenly evolved into a kind of short-term open war, involving border guards and security forces of both countries which also occupied roads and villages beyond the border and used heavy military equipment, causing the death of 55 citizens (35 Kyrgyzs and 20 Tajiks, both civilian and military) while 266 were injured, houses, schools and activities were destroyed and around 60,000 people evacuated (Filippo Costa Buranelli, Conflict in the Kyrgyz–Tajik Border – a Potential Turning Point for Central Asia, Central Asia and Caucasus Analyst Institute, 5 May 2021).

The casus belli of this bloody confrontation was the control of Golovnoi strategic water facility which delivers water to the three countries (Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan) which compose the Ferghana Valley. This recent explosion of violence is the result of the Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan’s inability to demarcate their common border (only 519 km of the total 971 km of borders were demarcated), which would allow them to solve the main linked issues, namely the competition between Kyrgyzs and Tajiks on land and water, the lack of a common and shared water distribution system, the existence of territorial enclaves (such as Voroukh, a Tajik enclave surrounded by Kyrgyz territory) inherited by the Soviet Union’s artificial delimitation of national borders.

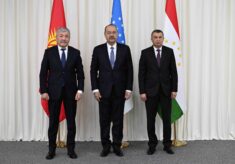

Tajik President Rahmon and Kyrgyz President Japarov called an immediate ceasefire (started on 1 May after three days of conflict), committing themselves to solve disputed issues diplomatically, first of all border demarcation. After the successful deal with Uzbekistan (March 2021) to complete border demarcation, Kyrgyzstan aimed to achieve the same goal with Tajikistan, proposing an agreement based on land-swap, but Rahmon appears less disposed to this approach, which involves sensitive issues of national sovereignty.

In late March, the head of the Kyrgyz security services, Tashiyev, proposed a land-swap (similar to the deal with Uzbekistan) to absorb Vorukh in Kyrgyz territory. Furthermore, in the following days Kyrgyzstan held military exercises in its Batken region, a move which Tajikistan may have perceived as a provocative and assertive approach. On 9 April Rahmon visited Vorukh, reassuring people that yielding Vorukh to Kyrgyzstan has never been in discussion (Thaw and frost across Central Asia’s borders, Eurasianet, 14 April 2021).

Russia and the other Central Asian countries express their profound concerns about a new source of instability in Central Asia, looking also at the impact of the ongoing withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan. Putin offered his mediation, considering that both countries host Russian military facilities as partners in the Collective Security Treaty Organization. Moreover, the proposal of Kazakh President Tokayev to develop a mechanism for the regulation of border incidents within the next Consultative Meeting of the Heads of State of Central Asia, has a high geopolitical relevance, showing the interest of the five republics to deal with the regional issues without external interference.