Kazakhstan’s decision to refrain from applying for BRICS membership appears a significant geopolitical U-turn if we consider the opening approach backed by Kazakh President Tokayev towards BRICS one year ago, describing it as a platform able to provide global security and stability, which hinted at a potential alignment of Astana in this bloc. However, Tokayev’s position is perfectly in line with the main goals and strategic interests of the Kazakhstan’s multi-vector foreign policy concept, which has represented the hallmark of this Central Asian country since the independence.

This unexpected decision to freeze Kazakhstan’s interest to join BRICS was announced by the Kazakh Presidential Spokesperson Berik Uali in the mid-October (before the geopolitical bloc’s annual summit), who explained that this position was based on the complexity of gaining membership, recognizing the United Nations’ role as the universal and “uncontested” organization where the most important international problems should be discussed (S. Sukhankin, Kazakhstan Pauses Prospective Application to BRICS, Eurasia Daily Monitor, 21:154, October 23, 2024). Nevertheless. President Tokayev attended the BRICS meeting in the Russian city of Kazan also giving a speech within which he underlined Kazakhstan’s readiness to cooperate with BRICS countries in different fields, not only deepening trade relations (which currently accounts for half of the Kazakhstan’s foreign trade) and transport cooperation (namely the different connectivity projects which encompass the country) but also in additional promising sectors as IT, critical minerals, food security, education and tourism, however without joining the association of states (S. Sakenova, Kazakh President Takes Part in BRICS Summit, The Astana Times, October 2024).

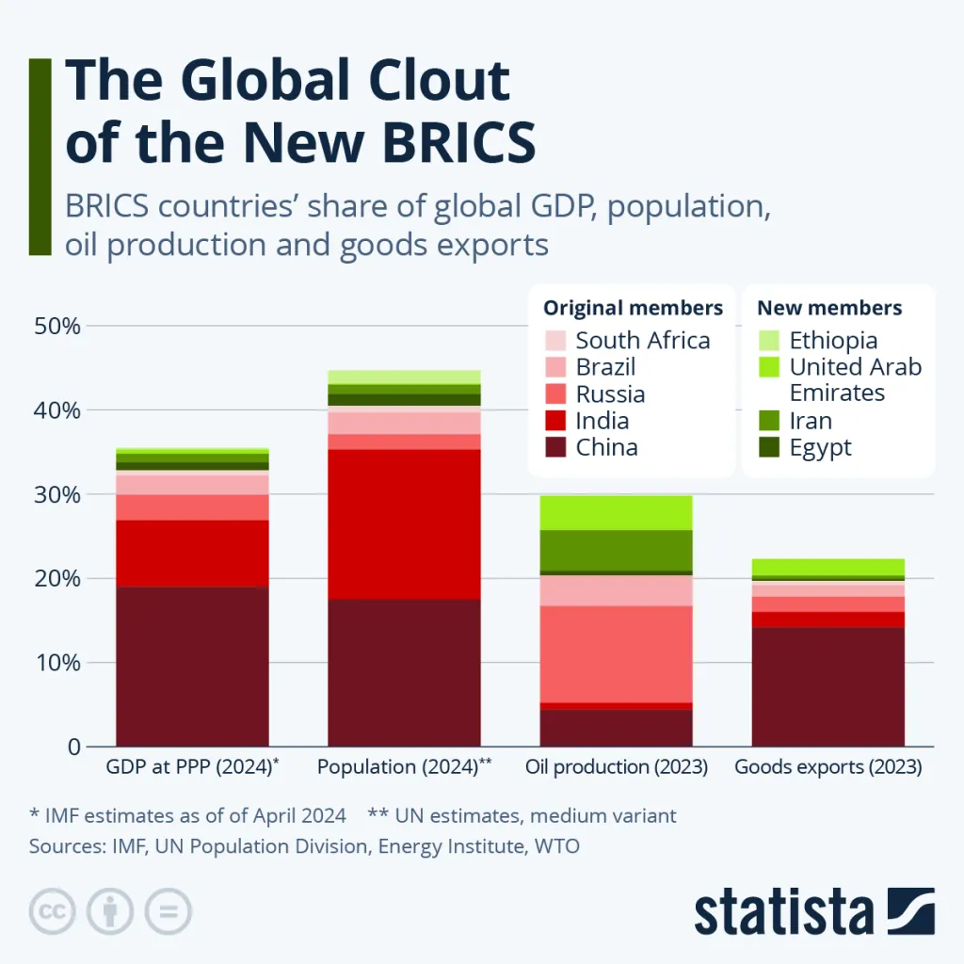

This apparently erratic position clearly explains Tokayev’s need to preserve its multi-vector foreign policy, mainly focused on balancing the influence of the regional powerful actors (China and Russia, both leading players in the BRICS) enhancing economic and political sovereignty and preserving national interests. As a matter of fact, the perceived anti-Western dimension of BRICS (aimed at promoting a new and alternative multipolar order based on the main economies representing the so-called Global South) could be harmful for Kazakhstan, which has further strengthened profitable economic and political relations with the EU. Only referring to 2023, trade turnover between Kazakhstan and EU reached $43 billion (A. Saini, R. Siddharth Jayaprakash, Kazakhstan’s BRICS Conundrum, The Diplomat, November 9, 2024), while new agreements have been implemented to supply European markets with critical minerals, rare earths, uranium for the nuclear energy production as well as cooperation to start green hydrogen production. Logically, Kazakhstan fears that its alignment to Russia and China joining the BRICS could alienate the cooperation and investments of western partners.