The dispute between Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan over the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the Blue Nile, the escalated tensions after Iran-backed rebels in Yemen launched attacks against ships in the Red Sea and the rivalry between Russia and China for control of ports in the Red Sea are the elements of the complex Horn of Africa geopolitics, often overlooked by mainstream attention.

The Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between Somaliland and Ethiopia, announced on the 1st of January 2024, is another serious complicating factor. This agreement grants Ethiopia access to 20 miles of coastal territory in Somaliland for commercial and military purposes for 50 years, including the port of Berbera. In exchange, Somaliland would receive recognition as an independent state and a share in the Ethiopian national airline. Berbera was a strategic port during the Cold War, changing hands from the Soviet Union to the USA. The new port, under development since 2013, had Ethiopia as a major shareholder (19%) until 2017, when its share was transferred to the British public investment body, CDC Group. DP World, a major Emirati logistics company, holds 50% ownership, while Somaliland retains 30%.

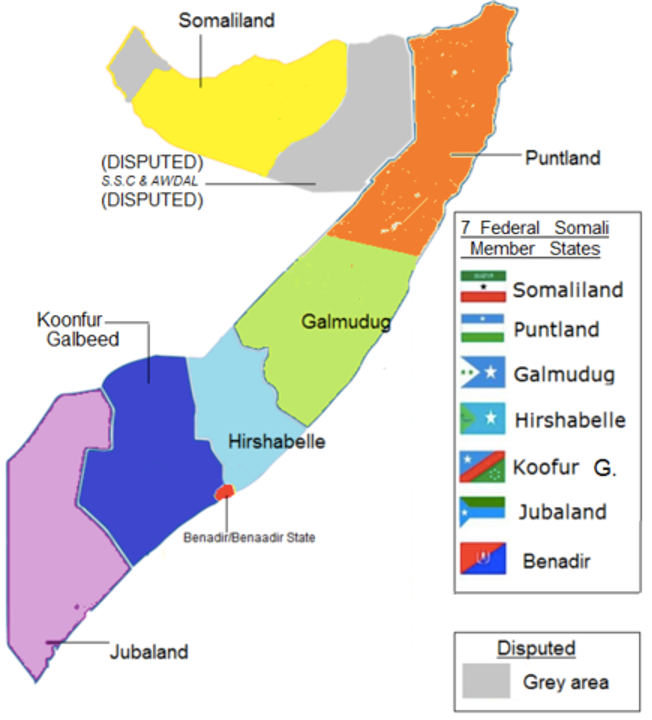

Note: Somalia is a federal state. Disputed territories are (from West to East): small three entities bordering Djibouti (former French Somaliland) and the Khatumo-SSC state recognised as part of the Somali federation, splitting away from Somaliland (former British Somaliland). Another region (Ogaden), was at the centre of a war in 1977-1978, because considered Somali territory in Ethiopia. Koonfur Galbeed is called also South West. Benadir hosts Mogadishu, the capital.

Somaliland’s strategic location along the Gulf of Aden, near the entrance to the Bab al-Mandeb Strait — through which one-third of the world’s maritime traffic passes — has made it an attractive partner for foreign governments seeking maritime access in the region. Despite declaring its independence in 1991, Somaliland remains unrecognized by the international community, with its borders often depicted on maps as dotted lines to indicate its ambiguous status. United Kingdom, Turkey, Taiwan, Ethiopia, Djibouti and UAE have diplomatic relations with the Somaliland. Somaliland has maintained relative stability and peace, in stark contrast to the ongoing turmoil in Somalia. This stability has been supported by remittances and investments from the diaspora, which have helped foster economic development. In 2023, Freedom House rated Somaliland’s freedom index as “partially free”, compared to Somalia’s classification as “not free”.

Despite Somaliland’s achievements, the African Union (AU) sensibly considers that a formal recognition could inspire other secessionist movements across Africa, such as Nigeria’s Biafra or Morocco’s Western Sahara. Since the AU’s formation in 1963, only two border changes have been widely recognized: Eritrea’s split from Ethiopia in 1993 and South Sudan’s independence in 2011.

Relations between Somalia and Ethiopia are now at a critical juncture. Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud responded swiftly and firmly, denouncing the agreement as a violation of Somalia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, as well as a breach of international law. He accused Ethiopia of harbouring expansionist ambitions toward Somaliland, a longstanding source of tension between the two nations.

Just a week before the MoU was announced, Somalia had expressed its willingness to resume talks with Somaliland, with Djibouti mediating. Although the memorandum is a preliminary agreement with formal contractual obligations yet to be negotiated, Somaliland is still legally part of Somalia. Consequently, the Somali government swiftly condemned the MoU as an illegal act of “aggression” interrupted the approach, and recalled its ambassador from Ethiopia. The situation is further complicated by the possibility of Al-Shabaab taking advantage of these tensions, potentially escalating attacks on Ethiopian forces in the Horn of Africa and using anti-Ethiopian sentiment to recruit new militants.

Despite these challenges, Somalia seems to be gaining increasing international support, with the European Union, the United States, the Arab League, and countries like Djibouti, Egypt, and Eritrea backing Mogadishu. The negotiations set for next September in Ankara could bring unresolved historical issues to the forefront, making this a critical moment for Somalia to engage, strengthened by the support of the international community.