Four years after the COVID-19 pandemic grinded international travel to a halt, more than 1,8 million people travelled to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, in June to perform the ritual Hajj, one of the five pillars of the Muslim faith. Prescribed to all Muslims at least once in their lifetime, the five-day pilgrimage during the Eid al-Adha holiday represents an important source of revenue and prestige for the Saudi family as guardian of the holy sites in Mecca and Medina. Nevertheless, reputational damage from frequent incidents is a considerable source of risk, as shown by the high death toll of the event this year.

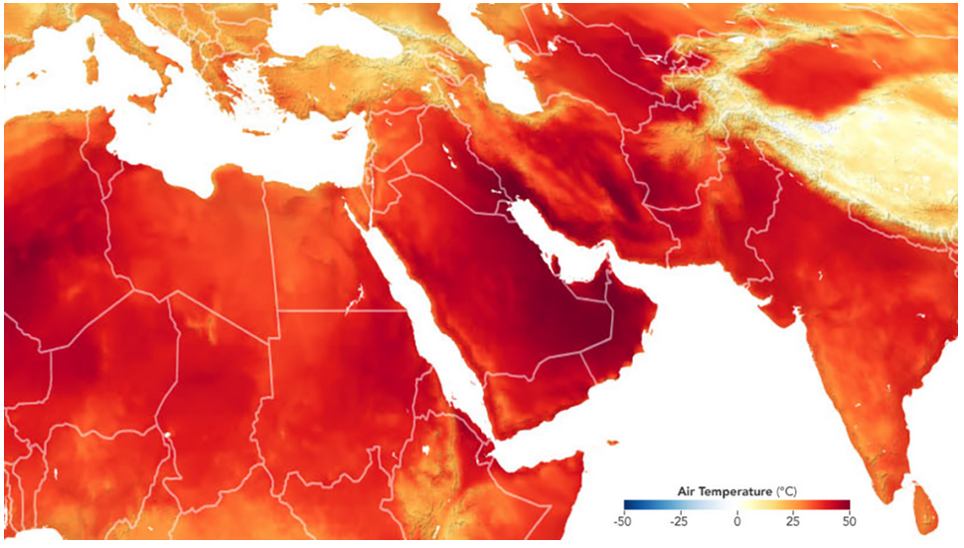

While dying close to the holiest sites in the Muslim faith is generally considered a blessing, especially for the elderly, news about the death of 1.300 pilgrims this year represented a considerable blow to the organisers. Reports suggested that the high price of hajj packages and permits granted by the Saudi authorities pushed many worshippers to travel on visit or tourist visas. As a result, unregistered pilgrims, who do not benefit air-condition buses or tents during their stay in Saudi Arabia, have been among the main casualties of the heatwave that hit the Arabian Peninsula and the Middle East in June 2024.

Temperatures have reached 51° Celsius in mid-June, causing heat strokes that overwhelmed police and ambulance services. It is not the first time that high temperatures have caused so many casualties among the pilgrims of the hajj, with more than 1.000 deaths in 1985, when temperatures reached 53° Celsius, but the climate change is without any doubt having an impact in the Middle East and North Africa, where extreme weather events are becoming more frequent and protracted. Estimates suggest that by 2040 rising temperatures could make the hajj unsustainable during the summer months, bringing the pilgrimage to a halt.

For this very reason and despite being the most prominent among the oil-producing countries in the region, Saudi Arabia has been leading efforts to decarbonise its economy and promote the energy transition on multilateral platform, such as the Conference of the Parties (COP), whose last edition took place in the UAE. Time is running and the transitioning away from the fossil fuels seems a priority for many governments in a region where the destabilising consequences of the climate change are already being felt. In Egypt for example, rising temperatures are compounding an energy crisis that is making the country extremely vulnerable.

The same can be said for other North African countries such as Algeria, where riots have erupted in Tiaret after months of water shortages. Despite demonstrators having blamed the authorities for mismanagement, climate change is shrinking water reservoirs to 20% of their capacity, according to some estimates. A problem common to drought-stricken Morocco, where satellite images last April showed the al-Massir Dam (the second largest in the country) drying up, containing just 3% of the average amount of water of nine years ago. An ominous sign of the future that awaits a region that will have to continue to adapt to rising temperatures.