Monthly Journal

March 2024

International Press Review

The most relevant events of the area through international sources

Integration of Kosovo and Serbia “endangered” by lack of progress

EEAS

On the first anniversary of the so-called Agreement on the Path to Normalisation, concluded in Ohrid, North Macedonia, by Kosovo and Serbia, the EU issued a warning that the European integration process for both nations is at risk as a year has passed and the agreement remains unimplemented, existing only on paper. The European Union External Action Service stressed the urgent need for Kosovo and Serbia to exit the current cycle of crises and tensions, urging a transition into a new European era by starting to implement the deal. The Agreement, the EU emphasized, promises a brighter future for the citizens of Kosovo, Serbia, and the broader region, as it might lead to the normalization of relations between Belgrade and Pristina.

Kosovo a step closer to Council of Europe membership

Balkan Insight

The Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly Committee on Political Affairs and Democracy voted in favour of Kosovo’s application for membership in the Council of Europe. The vote saw 31 representatives in support, four against, and one abstention. Opposition came from Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, according to regional media, and an abstention from Greece. Kosovo’s government hailed the decision, which recommended membership without conditions, as a step closer to joining, despite Serbia’s objections.

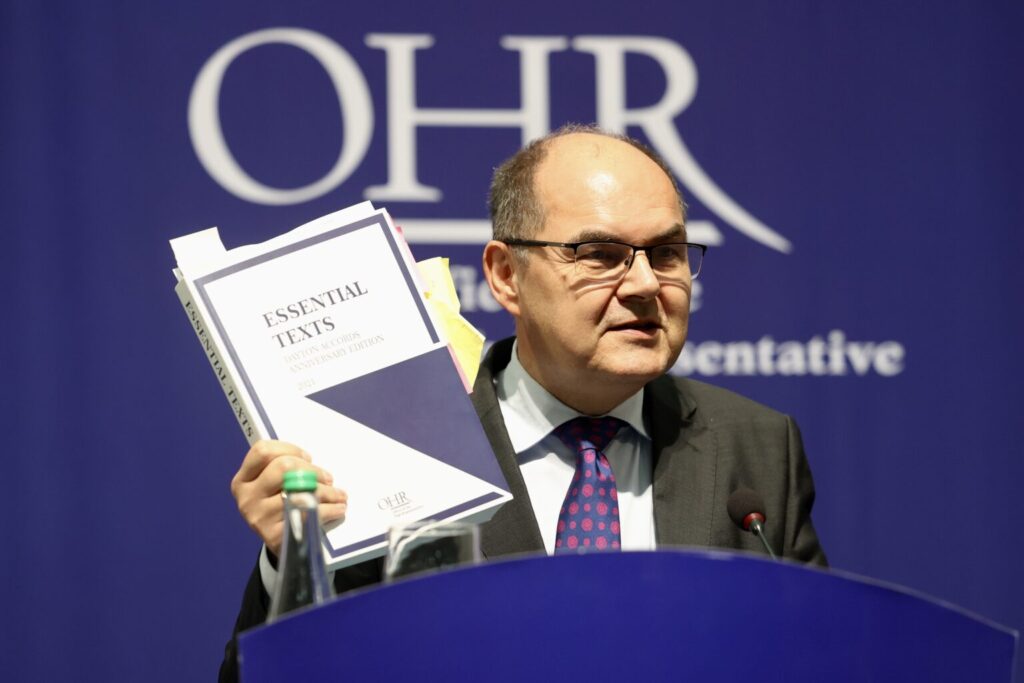

High Representative imposes electoral reform in Bosnia-Herzegovina

N1

The international peace envoy in Bosnia and Herzegovina, High Representative Christian Schmidt, exercised his executive powers to enforce changes in electoral legislation in the Balkan country, aiming to ensure “fair and free” elections through some technical and procedural enhancements. This decision received mixed responses within the country and abroad; while parties in Sarajevo and the international community, especially the US but not the EU, supported it, the Bosnian Serb leadership, that generally does not acknowledge Schmidt’s authority, strongly opposed it.

Bulgaria stops imports of Russian oil

Interfax

Bulgaria ceased importing Russian oil in March, ending de facto its current exemption from the EU’s ban on Russian oil imports, set to last until the end of 2024, ahead of schedule. Despite some EU members, including Bulgaria, initially having an exemption, Bulgaria opted to halt purchases of Russian oil before the deadline expires, a signal of further distance from Moscow. The decision might have negative impacts, as the country’s sole oil refinery is owned by Russia’s Lukoil and has a yearly capacity of 8,8 million tonnes. Lukoil also manages over 500 gasoline stations throughout Bulgaria.

Vucic escalating tensions, threatens actions towards Kosovo

Robert Lansing Institute

Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic is escalating tensions in the Western Balkans with threats towards Kosovo and an ultimatum to the global community, the Robert Lansing Institute claimed. The Institute stated that Vucic is heightening anti-Western rhetoric, after he moved troops near Kosovo, and he still engaging in talks with Russia, thus destabilizing regional security. Vucic issued lately a stark choice to Kosovo and the world: support Serbia or Kosovo, hinting at the Serbian army’s readiness to act at an opportune moment.

Pristina’s police head warns of ‘new Banjska’

RTK

In an interview with RTK at the end of March, Kosovo Police Director Gazmend Hoxha revealed information about Serbian criminal groups being trained in Serbian military barracks for potential attacks against Kosovo Police. “They can be groups similar to those in Banjska, perhaps in smaller numbers, but they can be more professionally prepared”, Hoxha stated. He assured readiness and effective response capacity from Kosovo Police. According to Hoxha, Kosovo has already raised the issue with the KFOR.

New local elections to be held in Belgrade

Balkan Insight

After failing to form a majority in the municipal parliament after the contentious December 2023 elections, new local elections will be held in spring in Serbia’s capital, most probably leading to new tensions. The Serbian opposition, while welcoming the rerun, continued to demand an international probe into the alleged December election irregularities and better conditions for future votes. Last month, the European Parliament passed a resolution urging an investigation into these irregularities by reputable international legal experts and institutions.

Kosovo Serbs to vote in a referendum to oust mayors

SeeNews

Kosovo’s Central Electoral Commission (CEC) has announced a referendum for April 21 in four Serbian-dominated municipalities in the north, aimed at deciding on the removal of their ethnic Albanian mayors. These mayors were elected in April last year with a mere 3% voter turnout, due to a boycott by the Serbian List party in northern Kosovo, an election that led to a severe crisis and to the injury of up to dozens of NATO soldiers during clashes with ethnic Serb protesters. The CEC’s decision to proceed with the referendum comes after validating petition signatures from North Mitrovica, Zvecan, Leposavic, and Zubin Potok.

Pristina decides to remove Serbian Cyrillic from road signs

Kossev

Amid the ongoing crisis stemming from the ban on the dinar, still unsolved, Kosovo’s decision to replace old road signs in Serbian Cyrillic with official ones in Albanian and Serbian Latin has further escalated tensions in the north of Kosovo. The Kosovo Ministry of Infrastructure began the installation of new road signs in March, inflaming the situation among the Serbian population. “Serbian Cyrillic has survived for centuries, it will also survive a small tyrant”, said the head of the Serbian governmental Office for Kosovo, Petar Petkovic.

Croatian President wants to run for PM, Constitutional Court against

ABC News

Croatia’s top court ruled that President Zoran Milanovic cannot run for the position prime minister, participate in the upcoming parliamentary elections or campaign for an opposition party, without resigning from his current role. After calling a parliamentary election for April 17, Milanovic announced his intention to run for prime minister with the opposition Social Democratic Party, triggering a political earthquake in Croatia.

Serbia to speed up production of military drones

Shephard

Serbian President Vucic announced plans to acquire 5.000 “Mosquito” (Komarac) expendable drones, made in Serbia, equipped with warheads, aiming at an enhanced military capability already by the end of this year. Although specifics of the drones were not detailed, the specialized portal Shephard Defence Insight speculated an allocation of up to 1,3 million dollars for deliveries scheduled between 2024 and 2025. Vucic urged also an increased government investment for additional staffing at the army. He emphasized Serbia’s neutral stance, asserting the need for strengthened defence to prevent aggression.

The Insight Angle

Christian Egenhofer

Christian Egenhofer, currently an Associate Senior Research Fellow at Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS), one of the most authoritative think tanks in Europe, where he led the Energy Resources and Climate Change Unit from 2000 to 2019. He also serves as a Senior Research Associate at the School of Transnational Governance at the European University Institute in Florence. Mr. Egenhofer holds visiting professor positions at SciencesPo in Paris and the College of Europe in Natolin, Poland. Previously, he thought at different other universities, including ULB Brussels, LUISS University in Rome, MGIMO in Moscow and the University of Dundee in Scotland. He published eight books and over 160 scientific articles and policy reports.

The Balkan region, including EU members like Croatia, Romania, and Bulgaria, has been grappling with a significant demographic challenge for decades, marked by low birth rates and a notable trend of emigration. What are the primary factors contributing to this phenomenon, and which countries are and will be more severely impacted?

A combination of socioeconomic and political factors contributes to the demographic challenges, marked by low birth rates and higher emigration, that face Western Balkans (WB) countries.

On the economic spectrum, the region’s economies are still in the transitioning and developing stages, with lower living standards compared to their Western European counterparts. These conditions make Balkan countries vulnerable to brain drain and outward migration as working-age populations seek employment opportunities and higher wages abroad. The emigrants in return contribute to their native countries’ economies through remittances, which comprise a significant portion of the region’s economies. In year 2021, WB countries received over $20 billion in remittances from migrants and diaspora members living abroad.

Along socio-cultural lines, reduced fertility rates across Europe and the Balkans, largely due to shifting attitudes toward marriage, childrearing, and gender roles have also posed demographic challenges across the region. Total fertility rates (children per woman) in 2020 were 1,5 in Croatia, 1,8 in Romania and 1,6 in Bulgaria, all below the replacement rate of 2.,1. The high costs of childcare and raising children coupled with a lack of social support have discouraged larger family sizes across a number of countries in the region.

Politically, countries like Croatia, Romania, and Bulgaria that have been EU members since 2013 and 2007, respectively, have been able to offer their citizens freedom of mobility within the bloc for longer periods of time, making emigration easier. Other landlocked nations like Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina have fewer natural barriers to outward migration. Eurostat data project that these countries will see the largest working-age population declines between the years 2022-2050 at -21,4% and -27,7%, further endangering their labour forces and economic prospects. Their economies remain weaker, making them more reliant on remittances from citizens working abroad – a dependency that inhibits domestic growth and development.

Every month, thousands of persons of all ages, but particularly young, are leaving the region to seek opportunities in wealthier EU countries, notably Germany. What factors make these EU countries attractive, and do the Balkan nations have the capability to address and counteract these pull factors?

The proportions of youth leaving the WB region towards Western Europe, and particularly Germany, are significant. Approximately 15-20% of students, aged 20 to 29 years, have emigrated from Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia and Serbia since 2010. Giving a context, the total net migration out of Bosnia and Herzegovina between 2010 and 2020 was more than 10% of its current population. If these trends continue, the populations of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia risk declining by over 25% by year 2050, accounting for high emigration and low birth rates.

Economic factors constitute key pull factors that make wealthier EU nations attractive destinations for WB emigrants. Contrary to Balkan countries, Germany and other Western European states have higher GDP per capita and offer significantly higher wages to potential immigrants. Moreover, Germany’s secure and growing labour markets offer employment and career opportunities for WB youth that are not readily available in the region. The strong pull of higher wages and better employment opportunities abroad are particularly appealing for the region’s youth who face a labour market characterized by unemployment rates 2-3 times higher than the EU average. As a consequence, while youth unemployment rates across WB countries exceed 20%, the number of employed Balkan residents under 30 in Germany grew over 150% between 2010 and 2020, with Albanian, Bosnian, and Serbian youth comprising significant shares.

Social factors also play a key role in pulling emigrants into the EU countries. When compared to WB countries, Western European states offer social welfare systems and public services, including healthcare, childcare, education, and eldercare that provide immediate financial and socioeconomic relief to new immigrants.

In the short-to-medium term, the WB countries face critical challenges in their efforts to curb the impact of migration pull factors. Given that the WB countries began at a much lower development baseline point compared to their Western counterparts, standards of living and wages across the regions will take generations to converge, despite economic reforms across the region. Social welfare systems also require critical long-term investments. The loss of human capital and the “brain drain” of skilled, educated youth poses serious long-term challenges if not tackled with urgency.

What is to be noted, however, is that a few WB countries are seeing success improving education and job training to increase competitiveness abroad or priming a virtual circular migration process. From a capabilities perspective, targeted measures to improve vocational training, develop targeted industry clusters and strengthen professional networks may help provide alternatives to emigration over time. Focussed reforms to targeted industries will also help offset pull factors over the long run, if sustained. Overall, the capacity to counteract pull factors in a generation or less appears limited, not accounting for unexpected economic transformation.

Is the EU indirectly benefiting from the demographic decline in the Balkans, by attracting workers and young people to address its own labour market challenges?

Evidence suggests that the EU is indirectly benefiting from the Balkan countries’ demographic shifts. It does so by attracting young workers to address its own labour market shortages. Data show that since year 2000, the WB countries of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, and Serbia have lost as much as 1-2% of their populations per year due to low birth rates and emigration. At the same time, the EU countries faces the challenge of aging societies and labour force losses. This demographic mismatch has formed migration opportunities that benefit both the EU and the Balkan countries.

From a political perspective, the benefits are not minor for incumbents in migrant-sending countries. While hundreds of thousands of WB citizens, predominantly young and well-educated, who live and work in Western Europe, send remittances back home, political incentives to curb emigration, decline, as emigration eases unemployment and political opposition at home.

At the same time, the EU has faced pressures to address its labour needs and has in recent years opened up its labour markets further to citizens from Balkan countries that are potential future members. In 2014, the European Commission adopted a proposal to allow citizens from Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, Serbia, and Turkey to work in EU member states without needing a visa or work permit. This proposal was a proactive measure to curb anticipated labour shortages in the EU and allow workers from the surrounding region access to the EU’s labour markets. These types of policies enable the EU to indirectly tap into the Balkans’ thinning workforce while delaying full integration of the region for political and economic reasons.

In short, the demographic decline facing the Balkans and the labour market needs facing the aging EU have created a mutually beneficial migration-context where both regions’ challenges are partially offset through migration, even as the full political integration of WB countries into the EU remains distant. The open labour markets help the EU tackle its shortages while remittances sent back to Balkan states boost domestic economies and political payoffs.

What are the primary negative consequences of emigration for the region in both the present and the long term? And what risks does the demographic decline pose to the economic and political stability of the Balkans?

Higher emigration rates have both immediate and long-term negative consequences for Balkan countries. In the short term, significant population losses caused by emigration are straining these countries’ welfare systems and economies. While remittances do provide immediate economic relief by bolstering household incomes and Balkan states’ GDPs, overreliance on them places these countries’ economies at risk of exogenous shocks if remittance flows decline.

In the long-term, the demographic decline poses serious risks to the economic and political stability of Balkan countries. Populations in the region are expected to shrink by up to 50% by 2100, if current trends continue. This will exacerbate the impacts of aging societies as the workforce decreases dramatically and support ratios plummet. Such declines threaten to undermine economic growth and development in the Balkans for decades to come.

Politically, population losses reduce the tax bases of these countries and weaken their geopolitical and geoeconomic influence on the global stage. Studies show that democratic instability could be exploited by external actors if governments lack the capacity to provide economic opportunity or basic services for their citizens and domestic electorates.

Thus, while emigration currently fuels Balkan economies, the long-term demographic decline poses severe risks to the region’s stability through slowed growth, aging populations, and potential political fragility. In the absence of policy measures intended to curb losses and boost birth rates and return migration, these costs may simply be too high for Balkan countries to bear.

Despite the challenges, there are also some benefits, particularly in the form of remittances, which are often higher than foreign direct investments. Do these positive aspects balance out the negatives associated with the problem?

With nearly 2,2 million people (roughly 10% of the region’s combined population), who have emigrated from the Balkans since the 1990s and another 1 million youth projected to leave the region over the next decade, the Balkan states face critical democratic and economic challenges in the long-term. These high emigration outflows pose significant brain-drain risks across the region. However, remittance inflows into the WBs have thus far provided offsetting economic benefits. In 2021, remittances to the Western Balkans reached over €15 billion, far exceeding foreign direct investment inflows, providing substantial economic relief for recipient countries. In countries like Albania and Kosovo, remittances make up over 10% of their GDP.

Despite the short-term economic relief, brain drain’s long-term consequences pose critical challenges for the region. As the Serbian President Vucic recognized in a 2021 speech, while remittances help families, Serbia is still losing its most educated and skilled citizens. These outflows of human capital provoke negative demographic shifts and result in skilled-labour shortages, that place the region at the verge of an impending demographic and economic crisis. These risks are higher in countries like Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and North Macedonia, where emigration rates are higher.

Thus, while remittances have provided a high degree of economic relief for WB countries over the last three decades, the negative impacts of human capital flight through brain drain still outweigh these benefits for the region’s economies and their long-term development prospects. To balance these consequential scales, WB governments must implement policy measures that attract emigrants back and create jobs and opportunities that incentivize skilled workers to pursue employment opportunities at home.

In conclusion, what policies would you recommend for governments in the region to address and potentially resolve this issue?

Improve economic opportunities and job prospects within the region to incentivize skilled workers to stay or return. This requires targeted investment in sectors like technology, renewable energy, and infrastructure to spur job creation. Kosovo’s Youth Employment Project is one example to this end.

Narrowing income inequality is critical. Increase wages, especially for highly educated professionals like doctors and engineers, to make salaries more competitive with those provided by Western European states. Albania for instance, increased salaries for doctors and nurses by 15% in 2021 to make healthcare wages more competitive with Western Europe.

Invest heavily in education and training programs to develop human capital and empower the workforce. This will make domestic economies less reliant on importing skilled labour. Offer tax incentives and startup grants for new businesses, especially those founded by returning emigrants. Streamline processes for certifying and recognizing foreign credentials and experiences so skilled emigrants have clear pathways to employment opportunities. Negotiate bilateral agreements with high-emigration countries for temporary work programs that allow circular migration patterns. Provide targeted social services, especially childcare in remote areas to disincentivize urban migration within countries to capital cities. Montenegro’s Centers of Excellence program, for instance, offers subsidized childcare in rural areas to disincentivize urban migration. And launch public campaigns promoting the benefits of staying in or returning to the Balkan countries for family purposes and quality of life.

The Key Story

Strategic trends

Bosnia and Herzegovina finally gets the green light for

opening EU accession negotiations – but without a date

Amid concerns over the secessionist policy of the Bosnian Serb leaderships and potential attempts by Russia to destabilize the region, and with the aim of strengthening ties with the European Union, EU leaders decided in March to finally approve the commencement of accession negotiations with Bosnia and Herzegovina, which has been a candidate country since 2022.

Bosnia has lagged behind Ukraine and Moldova, both of which received approval to begin negotiations already last December, resulting in a widespread sense of disappointment in Sarajevo and beyond. The latest development indicates however that the bloc plans to intensify its focus on Bosnia and the broader Balkan region.

The decision to initiate negotiations followed a surprisingly very positive recommendation from the European Commission, highlighting Bosnia and Herzegovina’s progress in implementing key reforms in recent months.

These reforms include the adoption of laws aimed at preventing conflicts of interest and combating money laundering and terrorist financing. Bosnia and Herzegovina has made also considerable advancements in enhancing its judiciary and prosecutorial systems, addressing corruption, organized crime, terrorism, and improving migration management. Furthermore, the Commission said, Bosnia and Herzegovina has maintained full alignment with the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy in recent times, marking “significant positive step and crucial in these times of geopolitical turmoil”.

After the Commission’s recommendation, the final decision on the negotiations was made by the European Council, where the topic of Bosnia remained, however, highly divisive. Some EU members, reportedly France, Denmark, and particularly the Netherlands, showed reluctance in granting the green light to Sarajevo, while others particularly Austria, Croatia, Slovenia, and Italy advocated against any postponement of the decision, stressing that the Balkans and this country should be given the same chances as Ukraine or Moldova, without further delays. The most significant hurdle, opposition from the Netherlands, was surmounted at the last minute when the parliament of the traditionally enlargement-cautious country narrowly voted against a resolution that ask to oppose opening talks with Bosnia. This decision meant that Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte was able to vote in favour of initiating negotiations at the European Council.

At this point, all EU leaders reached unanimity and approved the commencement of accession talks, a highly important move, also in symbolic sense. The “decision is a key step forward on your EU path. Now the hard work needs to continue so Bosnia and Herzegovina steadily advances, as your people want,” European Council President Charles Michel stated, reiterating that the place of Bosnia and Herzegovina “is in our European family.”

Although the agreement reached at the European Council marks a significant milestone, there is still a long journey ahead. Firstly, the EU must finalize a framework agreement on negotiations with the government of Bosnia-Herzegovina, which also requires unanimous approval by the EU member states. Only after this can an invitation be extended to an initial intergovernmental conference. Rutte emphasized that “Bosnia needs to be much more able to open the talks collectively by agreeing on a negotiating framework.” He pointed out that Sarajevo must now concentrate on completing five out of the fourteen required reform actions before accession talks can officially begin. In the official conclusions of the summit, EU leaders stated that a decision on the negotiation framework would be made as soon as the European Commission indicated that all the necessary criteria had been met.

Despite various shortcomings, the decision to open negotiation talks holds significant value, emphasizing the EU’s ongoing renewed interest in incorporating the Balkans into its ranks. This interest is partly driven by a desire to prevent further spread of influence from external powers, particularly from Russia and China, which have been particularly active in the region, both politically and economically, in the past years.

Further News and Views

Energy sector in the Balkan “close to collapse”, EU investments needed

Sources: CEPS

The CEPS think tank issued a warning that the Western Balkans’ power sector is on the brink of collapse. With about two-thirds of its electricity produced by lignite in over 40-year-old power plants, the region’s carbon intensity is triple that of the EU, subjecting its population to severe air pollution levels. More important, the outdated infrastructure struggles to operate at full capacity, and lignite-based district heating has already seen multiple failures. Retrofitting these plants to comply with EU emission standards is deemed economically unfeasible, CEPS said. Without intervention from the EU or Western entities, CEPS warned of increased dependency on Russian gas and potential energy supply disruptions, while China and Russia could fill the investment void. CEPS is currently advocating for direct investment and proposes integrating the Western Balkans’ power sector into the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) to encourage modernization and compliance with EU environmental rules, which the Balkan countries should already respect.

Serbia still leading in defence expenses in the Balkans, Albania and North Macedonia to invest more

Sources: Balkan Defence Monitor, STA, Hina

Serbia still tops the Western Balkans in relation to defence spending relative to GDP, currently at 2,0%, surpassing even the NATO member states in the region, which have not met the 2% GDP defence spending threshold still in 2023. However, Albania and North Macedonia are expected to achieve this target within this year, after their actual expenditures fell short of the 2% mark as initially planned for 2023. Bosnia and Herzegovina recorded the lowest military spending in the region, consistently below 1% of GDP. Slovenia, a NATO member, has gradually increased its defence budget since 2017 to 1,34% of GDP in 2023, yet it is not anticipated to reach the 2% goal until 2030. Croatia, on the other hand, allocated 1,8% of its GDP to defence in 2023, after exceeding the 2% benchmark in 2022, indicating a decrease in military spending.

EU - NATO

Kucova officially opened, Romania eyes biggest NATO base in Europe

Sources: NATO, Euractiv, Balkan Insight, Euronews

On the 4th of March, Albania officially reopened the Kucova airbase, transforming the decades-old facility into a modern centre for future NATO air operations. Situated approximately 80 kilometers south of Tirana, the new NATO airbase is set to support Albania and aid in NATO logistics, air operations, training, and exercises. The renovation of the base was financed by NATO with an investment of around 50 million euros and an additional 5 million from the Albanian government. The project marks a significant security enhancement for the Balkans and beyond, NATO and local authorities underlined. “NATO continues to strengthen its presence in the Western Balkans, an area of strategic importance to the Alliance,” NATO spokesperson Dylan White stated.

Meanwhile, a military base in Constanta, in Romania, is set to become the largest NATO military base in Europe, beyond the size of the US base in Ramstein (Germany). Planned to accommodate 10.000 soldiers by 2030, the base will see also logistics and troops relocated from Ramstein. The 2,7-billion-euros-expansion includes improvements to access roads and electrical infrastructure, with work already underway.

ECONOMICS

EU’s Growth Plan for the Balkans has “shaky details”

Sources: Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies

The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (WIIW) has criticized the European Commission’s New Growth Plan for the Western Balkans, presented in November 2023, as having “solid foundations” but “shaky details.” According to WIIW, while the Growth Plan effectively identifies the economic and political hurdles confronting the Western Balkans and introduces innovative elements, suggesting a necessary shift in the EU’s strategy towards the region, it falters in the specifics. The plan delineates four pillars that could underpin further development; however, its concrete measures and the translation of identified opportunities into actionable goals are seen as underwhelming. This discrepancy highlights the plan’s failure to fully leverage its foundational insights to effectuate substantive progress. However, if the EU modifies the plan to make it more concrete, it might succeed in accelerating development and the integration of the Balkans.

Stefano Giantin

Journalist based in the Balkans since 2005, he covers Central- and Eastern Europe for a wide range of media outlets, including the Italian national news agency ANSA, and the dailies La Stampa and Il Piccolo.