Monthly Journal

August 2023

International Press Review

The most relevant events of the area through international sources

Pristina against Paris over reintroduction of visas for Serbs and Kosovars

The Associated Press

Kosovo harshly criticized France’s President Macron for suggesting a possible review of visa-free travel for Kosovo and Serbia due to stalled talks and the tension between Belgrade and Pristina. Kosovo’s President Osmani warned such suspension would permanently hinder dialogue with Serbia. EU approved visa-free travel in Schengen area for Kosovo citizens starting from 2024, while Serbs can travel freely to the EU since 2009. Macron emphasized caution for Balkan stability and warned that visa-free travel for both Serbia and Kosovo may be “reviewed if both parties do not behave responsibly.”

Pro-Western Spajic nominated as PM-designate

Reuters

Montenegro’s President Jakov Milatovic has nominated Milojko Spajic, leader of the pro-Western Europe Now Movement (PES), as prime minister-designate. PES emerged victorious in the June snap elections following the defeat of long-standing ruler Milo Djukanovic, who stepped down after losing the April presidential elections after 30 years in power. Spajic’s nomination comes after gaining support from 44 lawmakers in the 81-seat Parliament in Podgorica, including members of PES coalition and parties representing ethnic minorities, like Bosniaks, Croats, and Albanians.

EU warns of potential sanctions against Serbia

Bne Intellinews

In response to the ongoing crisis between Serbia and Kosovo, the European Union has indicated that it might consider taking actions against Serbia if it determines that the government in Belgrade is not putting forth sufficient efforts to de-escalate the situation. The announcement follows punitive measures imposed on Kosovo after Pristina failed to effectively de-escalate tensions in the northern region of the country.

Vucic anticipates snap elections in 6-7 months

Anadolu

Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic announced the possibility of snap parliamentary elections within the next six to seven months. The country’s 250-seat unicameral legislature usually holds elections every four years. In June, Prime Minister Ana Brnabic expressed her willingness to resign amid protests triggered by mass shootings in May. Brnabic suggested early elections by the year’s end, deferring the decision to President Vucic. Consequently, if snap elections were called, it would be the third time Serbian voters are going to polls in four years.

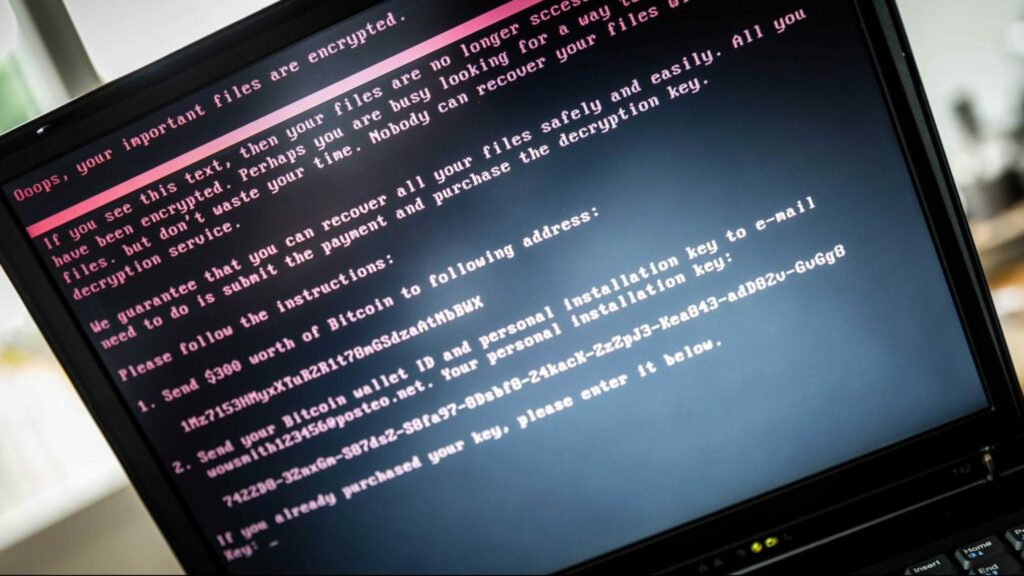

US offers 10 million-reward after cyberattacks against Montenegro

Balkan Insight

The US embassy in Montenegro has placed billboards in the capital Podgorica offering up to $10 million for information on cyber-attacks in Montenegro operated against American interests. The billboards refer to the cyber-attacks from August last year targeting a host of government services in Montenegro. The attacks compromised various public services, including the websites of the government and the Revenue and Customs Administration.

Austria warns against Russian influence in the Balkans

El Pais

In an El Pais interview, Austrian Foreign Minister Alexander Schallenberg warned against Russia’s capacity to influence the Balkans. He noted Russia’s use of fake news and disinformation to incite discord against Europe and the US, even generating potential new crises. Schallenberg acknowledged the volatility in the Balkans, citing complexities in Bosnia-Herzegovina, instability in Montenegro and ongoing tensions between Kosovo and Serbia. He emphasized that increased Western engagement would curb external interference. “What is valid for Ukraine is valid for the Balkans,” the conservative ÖVP politician argued.

Dodik charged for disobeying High Representative’s decisions

Radio Free Europe

Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik was charged by the prosecutor’s office in Bosnia-Herzegovina for defying decisions made by the international peace overseer, the High Representative Christian Schmidt. This move comes as a consequence of Dodik’s efforts towards secession, which have escalated over the past two years. Dodik’s recent actions include enacting two laws that were rejected by Schmidt due to their inconsistency with the Bosnian Constitution and the 1992-95 Peace Agreement that concluded the war. These laws suspended the Bosnian state-level Constitutional Court’s rulings within Republika Srpska and prevented Schmidt’s decrees from being published in the official gazette. The charges against Dodik carry a potential prison sentence of six months to five years.

The Insight Angle

Vujo Ilić

He is a Researcher at the Institute for Philosophy and Social Theory at the University of Belgrade and also holds the role of Policy and Research Advisor at Crta, a Belgrade-centred organization specializing in monitoring elections. Dr Ilić earned his PhD in Political Science from the Central European University in Budapest. His academic focus encompasses the spheres of democracy, elections and the complex terrain of political conflicts and violence within Southeastern Europe. He is esteemed as one of Serbia’s foremost authoritative political analysts.

You recently conducted research on a phenomenon commonly referred to as the ‘pandemic’ of illiberal democracies within the Balkans, using Serbia as a case study. What are the present risks for democracy in the region? Can certain leaders, such as Vucic, Orban, or Dodik, be accurately characterized as illiberal? How substantial are the existing challenges? Furthermore, why does the EU refrain from criticizing leaders in the region, particularly with regard to figures like Vucic?

There has been quite a serious decline of democracy in South-Eastern Europe. I see it as a part of a larger global wave of ‘autocratization’ that intensified after the 2009 recession. Hungary and Serbia are among the countries with the greatest decline of democracy globally; Poland and Turkey are also in this group. In our wider region, these countries turned into a new type of regime, which we call hybrid, as they have some characteristics of autocracies but still maintain formal democratic institutions. This type of regime evolves because democracy is still a prevailing global norm. Being a member of the EU or closely linked to it means there are limits to how far they can ‘autocratize’. However, the boundaries are being slowly moved. Once they win power in elections, these leaders slowly weaken the checks and balances on the executive branch of the government and the protection of individual and minority rights. This dismantling of liberal democracy increases their power; it makes them able to do things that were unthinkable a couple of years ago, and it is a terrifying image of the potential harm they are capable of doing. However, no unfair election is 100% safe in hybrid regimes.

I think there are always reasons for hope, and in the last couple of years, there were upset victories of democratic forces in North Macedonia and Montenegro or Budapest and Istanbul. It has to be said that the role of the EU has been ambiguous in this process. Under the EPP, it was an enabler of ‘autocratization’, at best. The EU chose to keep these authoritarian leaders close, maintain regional stability and hope the problems will eventually go away. Their position towards the rise of Orban or Vucic reminded me of the position towards the right-wing autocracies during the Cold War: “He may be a dictator, but at least he is our dictator.” For almost a decade, the worst these leaders could fear was being slapped on the cheek and greeted with “Hello, dictator,” which is what literally happened between Juncker and Orban in 2015. However, things have changed in the last couple of years, and I hope the next Commission will rethink the whole approach.

In Serbia, a significant movement opposing President Vucic emerged once again in May, yet as time progressed, the number of protesters dwindled, and no apparent alternative political course emerged from these protests. How do you interpret the current state of affairs within the country?

The last year was full of challenges for the ruling party and President Vucic. The invasion of Ukraine made Vucic’s balancing between East and West almost untenable. It also put the tensions in Kosovo and Bosnia under the spotlight, as the West tried to minimize the potential for troubles in the region while its focus was on Ukraine, which peaked with the ill-fated Ohrid agreement. The energy crisis and the inflation, which partially spilled over from the EU, made this mix of external challenges especially hard. Internally, after the 2019-2022 boycott, Vucic has to deal with very vocal opposition in the National Assembly. Like any other authoritarian, he despises pluralism, so for the last year, Vucic has repeatedly announced new elections in which he would “wipe out” the opposition, making the political life turn into a constant personalized political campaign. In early May, the two mass shootings in Serbia and how authorities handled them tipped into accumulated frustration and anxiety.

The mass gatherings that began in Belgrade and then spread to other cities were unprecedented. We have never seen such large protests recurring weekly, and they may be comparable to the judiciary protests in Israel this year. However, the political articulation of this evident dissatisfaction is lacking, which is not surprising. There have been many mass protests in Serbia in the last decade, but the relations between the protesters and political parties are very complex. Part of the problem is the government’s grip on the media and the smear tactics they use to silence the critics, first and foremost targeting political opposition and then everybody else – from academia to civil society and media. The citizens who oppose the government must also overcome the mistrust in the opposition, which the government-friendly media propagates. Another important reason why the political articulation of the May protests was challenging is the nature of the events. The mass shooting of children by a child was such a shocking and sensitive occasion that it made the discussion about the causes and political aspects of violence in society very charged and susceptible to emotional manipulation. For example, the parliamentary inquiry committee, established at the opposition’s request, was suspended by the majority after the lawyers hired by some of the parents of the killed children asked for that. In these circumstances, the political development of the protests was challenging, but it does not mean this issue will not resurface in autumn.

Considering the ongoing inflation and energy crisis, do you anticipate the potential re-emergence of protests in Serbia, as well as other countries in the region, during the autumn?

The salience of economic issues for protest mobilization is relatively low. The inflation and the energy crisis are indeed making people’s lives harder. The annual inflation rate in Serbia in 2022 was high, 12%; more than 9%, the highest level ever measured in the EU. Serbia is also threading on the verge of energy collapse. In a way, the collapse already happened in December 2021, when a major thermal power plant block broke down due to the poor quality of coal and years of underinvestment and mismanagement. Any short-term fixing of such problems still does not take care of long-term systematic ones, and actually, it is beginning to look like the government’s way to deal with the electricity sector will be to raise prices incrementally. Price hikes will add to the high inflation, making one problem feed another. But this is where the propaganda machine comes in. Vucic is a master of fearmongering. He often invokes catastrophic scenarios in which even bare existence is questioned and then presents himself as the saviour. This triggers genuine associations in a society that went through one of history’s harshest sanctions and hyperinflations. Many respond to such messages by saying, “Well, at least we still got electricity/food/heating.” So, it is tough to mobilize citizens on the economic issues. Instead, if we look at the recent mass mobilizations, the common thread is solidarity in protecting human life and dignity. Before the 2023 protests because of the mass shooting, the largest protests in 2018-2019 were triggered by the physical assault on an opposition politician. Even the 2021 environmental protests got momentum after hired thugs attacked the protesters. Things might be slightly different in other countries of the region. Mass protest mobilization can happen for various reasons. Still, I think things that move people, emotions, primarily anger, are often activated by a sense of injustice or threats to fundamental rights.

The region’s instability is intricately linked to the unresolved matter of Kosovo. Do you believe that Vucic and Kurti will be successful in establishing a lasting normalization agreement? Additionally, how detrimental is it to the democracies in Serbia and Kosovo that the general public in both Belgrade and Pristina remains largely excluded from these essential discussions about the status of Kosovo?

Kosovo is the central issue that affects or blocks many other regional political processes. As I already mentioned, the process got new impetus after the invasion of Ukraine, driven by the perceived risk that the instability in the region could get out of control. In many ways, maintaining the status quo was perceived as a less harmful option than rocking the boat. Looking back, the dialogue between Kosovo and Serbia changed the form and the dynamics several times, and we could see social, economic, or political focus, as well as the EU and the US switching as the drivers of the process. What we never saw during all of this time is the opening of the process and making it more inclusive. Of course, inclusivity may be used as just another buzzword, but without it, I do not think we can have any success in the normalization between people. The attitudes towards the other side are not softening, and my impression is that they may be hardening and that newer generations have more entrenched views about the conflict. This also limits the manoeuvring space for the politicians, who always have one eye on the next election date, to make a compromise. This was a cardinal mistake. The last decades look like a series of missed opportunities to involve the broader circle of political and social actors. So, as years pass, I see the probability of ending up with anything other than a frozen conflict steadily decreasing.

The EU enlargement process has come to a complete standstill. Do you believe that the proposals circulating in Germany about granting the Western Balkans access to the EU common market before full membership could offer a viable solution for the region? And what are the potential risks associated with prolonged exclusion of the Balkans from the European bloc?

Yes, the EU enlargement is stuck and needs to be revived. The EU is not seriously considering the Western Balkans enlargement, and the candidate countries are not doing enough to become members. What needs to happen is a sharp change of perspective, I think. We maintained a very linear idea of democracy and development, which predicts that the EU would set a certain threshold, the candidates would move towards that end, attracted by the membership as the reward, the EU would monitor this approximation and grant the membership after all conditions are fulfilled. However, we have seen that countries have been experiencing ups and downs, and after a while, membership stopped being a realistic political goal. For a candidate country’s political leadership, this creates incentives to manoeuvre and pursue other pathways strategically.

The distance from the EU membership becomes an important factor explaining why Western Balkans countries seek proximity to the external powers – Russia, China, and Turkey. So, what needs to happen from the side of the EU is for the membership to become a predictable, realistic goal. The EU needs to set a date for the future Western Balkans enlargement and, in this way, incentivize political actors in the candidate countries to make a new push towards that goal.

I do not think access to the common market would have such an effect. An equally important political and symbolic aspect of membership is attached to EU citizenship, having an EU flag on the Western Balkans national passports, or voting in the EU elections. Instead, ironically, not even the Conference on the Future of Europe engaged citizens from the candidate countries. I think for such a scenario to develop, there are some preconditions. Among them, the EU has to develop effective mechanisms for dealing with autocratization and corruption in the member states, it needs to adopt qualified majority voting in dealing with a broader set of issues related to the enlargement, and it needs to set the whole Western Balkans, no exceptions, back on the membership path. I think only a similar sequence of events could be genuinely transformative for the region; it is not likely, but I remain an optimist.

The Key Story

Strategic trends

EU evokes enlargement by 2030,

but the Balkans remain sceptical

In a significant development, a prominent EU leader has pledged to facilitate the expansion of the European Union into the Balkan region by 2030. This ambitious promise, however, was met with scepticism by the leaders of the countries in the Balkans, which have been waiting in an EU membership line for more than 20 years.

Addressing the attendees of the Bled Strategic Forum, in Slovenia, Charles Michel, the President of the European Council, emphasized the necessity for the European Union to enhance its “credibility” regarding its commitment to expanding into the Western Balkans in times of profound crises for the EU. The war in Ukraine “is not just devastating Ukraine: this war has a profound impact on the future of our continent,” Michel noted.

In Bled, Michel stressed the significance of discussing the “timing and homework” related to enlargement. Michel expressed his belief that both the EU and the Balkan nations should be prepared to be ready “on both sides — to enlarge by 2030.” “This is ambitious, but necessary. It shows that we are serious,” Michel said, adding that the EU will however not tolerate to include new members with open conflicts in their ranks. “There is no room for past conflicts within the EU,” Michel noted, as a clear reference to the Serbia-Kosovo issue.

The audience in Bled included the leaders of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, all official candidates for EU accession. The Balkan countries are in varying stages of their negotiations for EU accession. Progress has stalled for many as they grapple with the implementation of core EU prerequisites for membership, encompassing aspects such as the rule of law, democratic elections, and media freedom.

Even if Michel’s address at Bled was widely interpreted as significant, marking one the first instances of an EU leader specifying a concrete accession date for countries within the region, political leaders in the Balkans have collectively conveyed a prevailing sense of doubt regarding the timeline proposed.

According to outgoing Montenegrin Prime Minister Dritan Abazovic, for instance, the year 2030 appears to be “distant,” and while nations within the region possess clear objectives, there are instances when it is the EU leadership itself that seems uncertain about their own intentions, he claimed. Serbian Prime Minister Ana Brnabic contended that the region has grown weary of the continual shifting of objectives from EU side and the prevailing perception that the efforts of these countries consistently fall short of expectations. Furthermore, she claimed that Kosovo is still part of Serbia, implicitly excluding any long term and definitive solution on the issue, while Kosovo’s PM Kurti accused Belgrade of confusing “reality and fantasy” when speaking about Kosovo as part of Serbia.

North Macedonia’s Prime Minister Dimitar Kovacevski found optimism in Michel’s affirmation that the EU intends to “affirm its commitment to expansion,”. However, even Kovacevski highlighted that the enlargement process has become excessively protracted and he pointed out that back in 2003, when the EU formally affirmed the European prospects for the Western Balkan nations, North Macedonia was known as Macedonia, and Montenegro and Kosovo had not yet gained their independence. Also, Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama responded to the 2030 deadline with a touch of cynicism. Drawing a parallel to the swift advancement of Ukraine’s membership aspirations following Russia’s aggression, he joked about the prospect of determining which entity in the Balkans should provoke the other to expedite the enlargement procedure.

In a final development that might amplify skepticism within the region, a European Commission spokesperson commenting Michel’s statements conveyed on that the enlargement process is predicated on merit and not by deadlines, as the one mentioned by Michel. And the Commission emphasized that candidates should attain EU membership only when they have adequately prepared for it, before or after 2030.

Further News and Views

After Vulin, US sanctions four Bosnian Serb high-level politicians

Sources: US Department of State, N1, The Associated Press

The US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) has imposed sanctions on four Bosnian Serb politicians and officials, citing their roles in advancing a controversial Republika Srpska (RS) National Assembly law. This law, supported by RS entity president Milorad Dodik, aims to declare decisions of the BiH Constitutional Court inapplicable in RS, undermining the Dayton Peace Agreement’s implementation.

The sanctioned officials are RS Prime Minister Radovan Viskovic, RS National Assembly Speaker Nenad Stevandic, Justice Minister Milos Bukejlovic, and the Serb member of BiH tripartite Presidency Zeljka Cvijanovic. The move targets those responsible for obstructing state institutions and threatening Bosnia’s stability, sovereignty, and European integration aspirations, Washington noted. “The US thinks in this way they can discipline someone who does not share their views, but we are not concerned about these sanctions,” said Dodik, who is already under US sanctions. Meanwhile, also Serbia said it will ignore the sanctions against the Bosnian Serb leadership.

In July, US sanctioned also Aleksandar Vulin, the director of Serbia’s secret service, and an influential political figure in Belgrade, amid allegations that he assisted Russia in undermining Balkan stability and facilitated drug and weapons trafficking.

Croatia offers its ports to Ukraine, US working with Romania on grain transport

Sources: N1, Deutsche Welle, Devdiscourse, Romania-Insider

In a potentially strategic move, Ukraine has announced its intention to utilize Croatian ports situated on the Danube and the Adriatic Sea for the export of its grain. This decision comes as a response to the Russian blockade of the Black Sea, which was enacted after Moscow’s abrupt cancellation of the agreement for grain exports in mid-July and after the bombing of two Ukrainian ports on Danube. The Ukrainian Foreign Ministry, after Croatia offered its ports to Kyiv, has devised a plan to transport grain along the Danube River to Croatia and then onward via rail to Croatian Adriatic ports. It is not clear when the plan could be implemented and how much grain from Ukraine Croatia can handle.

In tandem with this move, the United States and Romania have emerged as key partners in bolstering Ukraine’s grain exports also through the Danube river. While specifics remain undisclosed, a senior U.S. State Department official indicated that efforts are underway to potentially double the grain exports using this alternative pathway.

EU - NATO

‘Athens Declaration’ reaffirms importance of enlargement

Sources: European Western Balkans, EUobserver, Kyiv Post

Leaders from EU candidate and potential candidate countries convened in Athens, heeding the invitation of Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis. The meeting commemorated the 20th anniversary of the EU-Western Balkans Summit held in Thessaloniki, where the EU had pledged a path to membership for the region. Besides Western Balkan leaders, heads of state and prime ministers from new candidate nations Ukraine and Moldova, as well as EU member countries within the region, and the Presidents of the European Commission and European Council were present. The joint Declaration reconfirmed backing the Ukrainian sovereignty and territorial integrity, while also refocusing the enlargement process in the Balkans. The Declaration highlighted a call for a revitalized and concentrated expansion procedure that remains substantial and believable, avoiding any shortcuts. The leaders affirmed also their dedication to aiding Ukraine and Moldova in progressing through their accession journeys after fulfilling necessary reforms.

ECONOMICS

Almost half of Serbian youth planning to emigrate

Sources: N1, Westminster Foundation for Democracy, German Marshall Fund, OECD

In its 2023 report, published this month, the National Youth Council of Serbia (KOMS) pointed out the negative trend of youth leaving Serbia, which had become endemic. The annual Alternative Report indicated that nearly half of Serbia’s young population (49,2%) had planned to depart the country, while only 11% were determined to remain. The leading reason for their intended migration was a higher standard of living (32,2%), closely followed by the aspiration for a dignified life (27,7%). The high emigration rate of young people from the Western Balkans is having negative consequences on the region’s economies, not only in Serbia. The loss of human capital and slower economic growth are some of the negative effects of high levels of emigration. Additionally, the exodus of young people has led to a significant decrease in the GDP of some countries, leaving their already imbalanced economies on shaky ground.

Stefano Giantin

Journalist based in the Balkans since 2005, he covers Central- and Eastern Europe for a wide range of media outlets, including the Italian national news agency ANSA, and the dailies La Stampa and Il Piccolo.