Monthly Journal

February 2023

International Press Review

The most relevant events of the area through international sources

Russia will ‘defend’ itself if Bosnia joins NATO

N1

Russia asserted once more that Bosnia and Herzegovina’s NATO membership would be seen by Kremlin as an “anti-Russian” move and declared that Russia would respond, without further elaborating on it. The Russian Embassy in Sarajevo stated that Bosnia and Herzegovina are free to join any international organization, such as NATO, if the majority of its citizens desire it, but that they must understand that “if it joins a bloc whose main goal is to destroy Russia,” then “Russia, as a free country with an independent foreign policy (…) has the right to defend itself.”

Kosovo’s President claims Moscow tries to destabilize Balkans, Georgia and Moldova

Sky News

Kosovo’s President Vjosa Osmani accused Russian President Vladimir Putin of attempting to “export” the Ukrainian conflict to Kosovo and other countries like Moldova and Georgia. Osmani told Sky News that Putin is attempting to “distract the West’s attention away from Ukraine”. Russia “would be able to do so by fomenting other conflicts in Europe, whether in Moldova, Georgia, or the Western Balkans,” Kosovo’s President added. According to Osmani, destabilization attempts, such as operations under a false flag, were already made in the past months. Russia sent “paramilitary forces disguised as civilians through illegal routes to our territory, and then they send weapons,” Osmani claimed.

Serbia looking to the West to buy new fighter planes

Bloomberg

Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic has pledged to increase defence spending in order to upgrade the country’s military, including the possible purchase of French warplanes and the provision of “competitive” wages for elite units. Vucic said at the IDEX 2023 arms fair in Abu Dhabi that this Balkan nation, which had previously looked to Moscow and Minsk to modernize its air force, may spend an additional 700 million euro this year on top of the defence budget. The funds will be used to upgrade tanks, purchase 200 armoured vehicles, combat drones, and attract recruits to elite corps. Around three billion euros might be invested for buying French fighter planes.

North Macedonia targeted by cyberattacks and bomb hoaxes

BNE Intellinews

After Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Albania, and Montenegro, North Macedonia was also targeted by unknown assailants via cyberattacks and bomb hoaxes, causing significant disruption in Skopje. North Macedonia’s Prime Minister Dimitar Kovacevski stated that the recent cyber-attacks and false bomb threats are linked to Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine. The Skopje government has adopted a set of high-priority measures aimed at improving the security of information systems in public sector institutions. The measures will be implemented as soon as possible, authorities said.

Around 40.000 Serbs left Kosovo in the past decade

Beta news agency

According to the NGO Kosovo’s Center for Affirmative Social Actions (CASA), over the last ten years, the number of Serb children in Kosovo’s primary and secondary schools has decreased by 10.000, indicating that approximately 40.000 Serbs have left the territory. CASA estimated that 120.000 Serbs lived in Kosovo ten years ago, and that the population has since shrunk to around 80.000. CASA explained that the Serbs were fleeing Kosovo due to a lack of security as much as a lack of employment opportunities.

The Insight Angle

Nikola Dimitrov

Non-resident Fellow at Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) and member of the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) and the Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group (BiEPAG). Dimitrov served as Foreign Minister of North Macedonia (2017 – 2020), and as Deputy Prime Minister of European Affairs (2020 – 2021).

North Macedonia can be viewed in the Balkans as an example of a country overcoming complex bilateral issues – even through painful moves such as the name change – in order to continue on its Euro-Atlantic path. What is the ‘lesson’ that North Macedonia can teach the region, especially to Serbia and Kosovo?

Let’s frame it more humbly, as a lesson we have learned, that may or may not be useful for our neighbours. First, both governments wanted a solution of the name dispute that has dragged us down for almost three decades. The Prespa Agreement was homemade, negotiated by the two sides. Our mediator and some international friends helped, but the ownership is clearly with North Macedonia and Greece. We managed to overcome the mutual blame game, usually a sign that substantial negotiations are not taking place, by careful examination of the motives and intentions of the other side. We invested in building trust, both personal between me and my counterpart, and dear friend Nikos Kotzias as foreign ministers and chief negotiators, as well as between the governments. We learned the sensitivities of the other side as if they were our own. And made our best to come up with a compromise covering the key concerns of both sides. We focused on interests rather than positions. We consulted regularly on communicating the compromise with the public, trying not to damage the other side when defending the compromise among our own citizens. In the last stage of the process, there was an interesting switch for both of us: we no longer perceived each other as adversaries. We have gradually become allies and our adversaries were the opponents of the compromise from both countries. At that point, the political costs of a failure were at least as big as the political capital spent on solving the problem. Because, to be honest, solving a three decades long dispute can never be about the next elections. It can only be about the next generation.

Do you believe the Serbian and Kosovo leaders are on par with the Macedonian and Greek leaders who signed the historic Prespa agreement? Alternatively, do you think that the Kosovo issue is too complex to be compared with?

I will underline here another lesson from the Prespa Agreement – a negative one – that resonated throughout the Western Balkans, including in Serbia and Kosovo, and severely undermined the credibility of the EU. North Macedonia lost generations stacked in the EU’s waiting room, because of the name issue. Having concluded the Stabilization and Association Agreement with the EU ahead of Croatia, now a member state since 2013, we have become a veteran or a professional EU candidate country. A baby born in 2005, when we became a candidate, is coming of age this year. To support the referendum on the Prespa Agreement, European leaders rushed to Skopje and promised Macedonian citizens that if the problem gets solved, North Macedonia would finally be allowed to open its EU accession talks. After all, we had had over ten positive recommendations by the European Commission that the country is ready to start negotiations. The last remaining obstacle was the name issue. The European Council conclusions from June 2018 set out the path towards opening accession talks in June 2019. To cut a painful story short, North Macedonia delivered but the EU failed to do so. This has sent a troubling and rather discouraging message to Balkan leaders. The vision of a stable and prosperous Balkans inevitably includes its European future, where borders become less or not relevant at all. This should be done through a merit-based process supporting and monitoring reforms towards our countries becoming vibrant democracies governed by the rule of law. European integration is an important incentive for leaders to solve long-standing disputes. If it is credible and realistic, it would be a significant impetus to tackle the remaining unresolved issues in the region.

Despite all of Skopje’s efforts, North Macedonia still faces challenges. How do you see the current tensions with Bulgaria, and how dangerous they are to the EU integration process of North Macedonia and Albania?

Bulgaria turned from a champion to the biggest obstacle of our European future in a matter of few weeks in 2019, taking the enlargement a hostage of issues of history and identity and completely derailing the Friendship Treaty signed two years before. “We should not allow a legitimisation of Macedonianism, of ideologies from former Yugoslavia and the Comintern, to find a place in the EU,” Bulgaria’s president Rumen Radev said in May last year. His words echo the infamous editorial of Russia’s state news agency, which stated that “Ukrainism is an artificial anti-Russian construction.” Indeed, there are incredible similarities between Putin’s narrative on Ukraine and Bulgaria’s official narrative on ethnic Macedonians. Both are artificial nations, mistakes of history, created by Lenin and Tito respectively, claim Moscow and Sofia. Ukraine is a Russian land, while North Macedonia is Bulgarian. The Macedonian language is a dialect of the Bulgarian (Bulgaria submitted a unilateral declaration to that effect in Brussels), while Ukrainian is a dialect of Russian. The rights of Russians/Bulgarians are endangered and they must be enshrined in their respective constitutions.

The set of decisions and documents that seemingly unlocked the EU accession talks for North Macedonia last year did not solve them, but instead imported issues of history and identity in a process that should be about democratic and economic reforms. Even if North Macedonia manages to amend its Constitution, its progress towards EU membership will not only be about the rule of law, democracy and other European standards, but the dynamic will depend on whether historians agree with their Bulgarian counterparts. For the first time in the history of enlargement, the European Commission will report on historical and related issues. This risks completely side-lining the process of accession and sets a dangerous precedent. By giving in to the most nationalist demands of an individual member state, the EU might encourage others do the same. Considering that there are minorities and bilateral issues between all aspirants and their EU neighbours, the precedent opens the pandora’s box threatening to bury the whole process of enlargement.

The result of all of this is more stagnation, more frustration, and a potential for a perpetual political crisis in North Macedonia. A recent poll shows 65% of the citizens think EU’s attitude is unfair, and extorting, with those who believe the country will join in the next five years dropping to 12%. The ethnic Macedonians are offended and out of 42% of citizens who think that the country has an external threat, 27,6% see Bulgaria on top of the list, followed by Russia with 4%. It will take political leadership in both capitals and in the EU to overcome the current negative state of play and find a positive way out based on mutual respect, the integrity of the accession process and the acceptance of the right of the ethnic Macedonians to self-expression by Sofia. Because, good-neighbourly relations are a two-way street. In Europe, in 21st century, this is certainly not much to hope for.

The EU integration process remains largely stalled. How dangerous is it, given the geopolitical situation and Russia’s aggression against Ukraine?

In our region, EU enlargement turned from a perceived stairway to heaven into a road to nowhere. There is a process, yes. But it is difficult to see what does it achieve on the ground in terms of reforms, and where does it lead to. For some member states, the reform of the internal EU decision-making is a precondition for taking new members. If this failing template is applied to Ukraine and Moldova, there will be enormous frustration and disappointment. The gap between Kyiv’s expectations on accession and the reality within the EU is already visible. This in turn is embraced by the Russian narrative: The West cannot be trusted. That is why Europe needs a credible and realistic interim goal on our way to EU membership backed by political will, European funds, a set timeframe, in a flexible and dynamic performance-based process where reforms will be rewarded and backsliding sanctioned. Not an alternative to full membership, but something beneficial for the citizens on their way to membership, be that joining the Single Market or an initial membership without veto rights. This strategic agenda will have to include institutional or political tools to prevent arbitrary individual vetoes by member states unrelated to the Copenhagen criteria and irreconcilable with European values.

Russia targeted North Macedonia both before and after the country joined NATO. And now Moscow is ‘advising’ Bosnia and Herzegovina not to join the Alliance in order to avoid negative consequences. How would you rate Russia’s role in the Balkans?

In our region encircled by EU member states, we have three NATO allies and five EU candidate countries, with Kosovo recently applying for it. I am one of those who think of Russia as a spoiler. Moscow welcomes failing narratives in the Balkans, that can be then used as counter-narratives in its own neighbourhood. That the West cannot be trusted and will never deliver. The modus operandi is often adding fuel to existing grievances and disputes and disinformation campaigns. In times of a genocidal war on our continent, we have to do everything we can to help the victim, and we have to make the aggression as costly as possible for the brutal aggressor. We, however, also have to consolidate the rest of the continent and this must include the Balkans. If the EU cannot integrate the countries of the Western Balkans that have been promised membership as back as 2000 and that have been working on this vision ever since, it will certainly send the wrong message to Ukrainians who are fighting and getting killed for their European choice.

The Key Story

Strategic trends

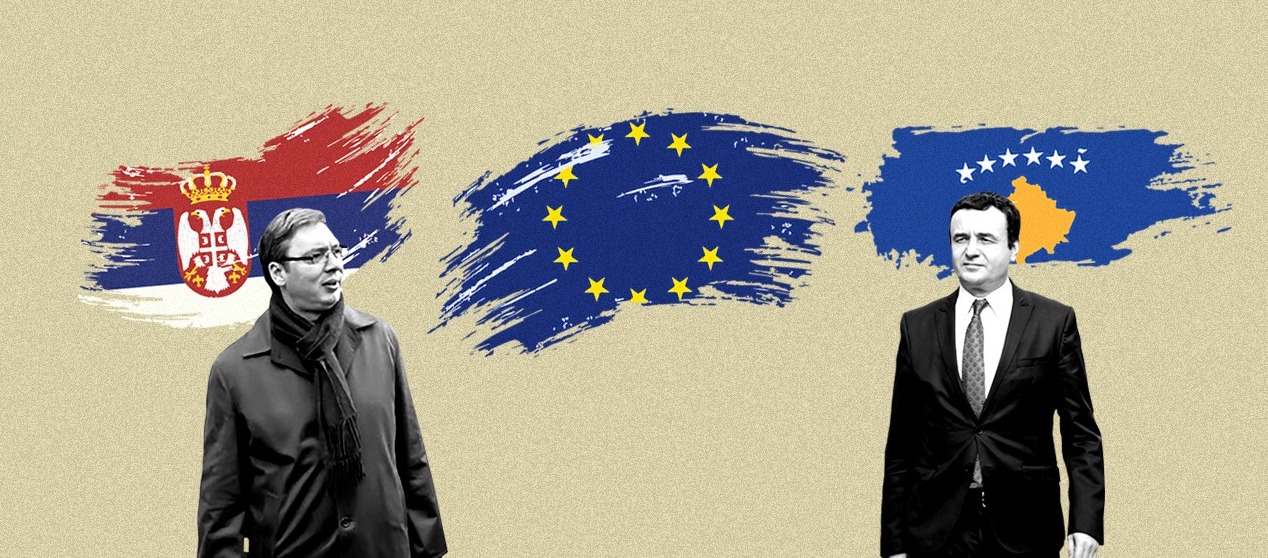

Serbia and Kosovo maybe closer to a historical deal,

but more work needed

Kosovo and Serbian leaders met in Brussels at the end of February, as the European Union increased pressure on them to reach a breakthrough deal that will lead to normalization of relations between the two countries. After more than two decades of feuding, the two sides have admitted that they are feeling increasingly pressed by Western governments to reach an historical agreement.

Following the February 27 meeting in Brussels, EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell stated that the leaders of Kosovo and Serbia had endorsed a Brussels peace plan but needed more talks to agree on how to implement it. Another leaders’ meeting, according to Borrell, will be required in mid-March, with a possible final agreement expected for the end of next month.

“I am pleased to announce that” Vucic and Kurti “have today agreed that no further discussions are needed on the European Union proposal,” Borrell informed.

The plan, which was quickly made public, was initially floated as Franco-German. The plan’s main goal appears indeed to be to force Serbia and Kosovo to recognize their mutual existence de facto, without going so far as de jure recognition. Furthermore, Belgrade should allow Pristina to try entering any international organizations, including the United Nations, where Russia and China, historically close to Serbia, have the right to veto.

The proposed deal “sets out that people can move freely between Kosovo and Serbia using their own passports – mutually recognized – IDs and license plates. It entails that people can study and work without wondering whether their diplomas and where they obtained them may be an issue,” Borrell confirmed. Furthermore, the deal “can bring new economic opportunities through increased financial assistance, through business cooperation, and through new investments in Kosovo and Serbia.” “For the Serbs in Kosovo, it means more security, certainty and predictability – when it comes to their protection and rights in Kosovo – including for the Serbian Orthodox Church and the Serbian cultural and religious heritage sites,” Borrell noted.

“Further negotiations are needed to determine specific implementation modalities of the provisions,” Borrell added. However, just the fact that the EU said that both parties agreed that the EU plan is final and acceptable in principle suggests that a historical deal between Serbia and Kosovo might be in sight.

Following the meeting, Vucic and Kurti claimed though there had been no breakthrough and each attacked the other, addressing their domestic media to emphasize they were not making concessions, despite strong pressure from Europe and the US to reach an agreement. Vucic, in particular, dismissed the talks as ineffective. “We don’t have a roadmap,” he insisted, while agreeing to continue with talks. Kurti was more upbeat, saying he would have been willing to sign an agreement if Vucic had been.

Opposition forces, critics and experts in the region continue wondering what kind of benefits Serbia and Kosovo would have by accepting the plan. With the EU integration process stalled, it is unclear what benefit Serbia would gain from agreeing on the plan without envisioning concrete steps toward full EU integration. Also, Kosovo may wonder if the plan is still of interest, given Pristina’s position that any agreement must include “full mutual recognition.” Furthermore, there are still concerns about how both leaders would sell any potential agreement to their respective populations.

According to a senior EU official, quoted in local media in the region, Russia is actively attempting to derail the two sides’ negotiations.

Further News and Views

Dodik denies Srebrenica was a genocide, USA reacts promptly

Sources: Radio Free Europe, N1, European Western Balkans

Milorad Dodik, the current president of the Bosnian Serb entity Republika Srpska and a pro-Russian nationalist and secessionist, sowed discord in Bosnia once again by denying that the massacres in Srebrenica in 1995 amounted to genocide. “There was no genocide there. We all know that, but they keep trying to force it on us,” Dodik said, causing rage among victims and survivors. Dodik reacted after the international community’s High Representative in Bosnia and Herzegovina, German Christian Schmidt, amended legislation on a memorial centre for victims of the 1995 Srebrenica genocide to allow funds intended for burials to be used to help run the facility.

In a video statement, US Ambassador Michael Murphy stated that Dodik’s “repeated attempts to deny the genocide at Srebrenica, as he did again yesterday, cannot change the facts and cannot change the truth.” Such efforts by the secessionist leader of Bosnia’s majority Serb region, as well as the glorification of war criminals from the brutal Balkan conflicts of the 1990s, he called “irresponsible” and said they “deserve condemnation.” Several political parties stigmatized Dodik’s words, warning that denying war crimes and the genocide can have a destabilizing impact in the country.

Oppositions protests in Tirana, promise “revolution” against PM Rama

Sources: The Washington Post, Euronews

Thousands of supporters of Albania’s political opposition marched in Tirana, calling for Prime Minister Edi Rama’s resignation for alleged corruption and mismanagement of the country’s economy. Protesters included Sali Berisha, Albania’s controversial former president and prime minister who now leads the centre-right Democratic Party. “We are in a revolution,” Berisha declared, adding that “we are a democratic force, not a violent force.”

EU - NATO

NATO, US to help Moldova amidst Russian destabilizing efforts

Sources: NATO, Radio Free Europe, The Associated Press

The US and NATO have promised Moldova various forms of assistance, as the former Soviet republic fears it will be the next target in the Kremlin’s sights after Ukraine.

Moldova’s president accused Russia of plotting to destabilize her country’s leadership, prevent it from joining the European Union. President Maia Sandu made her remarks following Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy’s announcement last week that his country had discovered a Russian intelligence plot “for the destruction of Moldova”. Sandu went on to say that the plan involved Russian, Montenegrin, Belarussian, and Serbian citizens planning to entering Moldova to incite protests in order to “change the legitimate government to an illegal government controlled by the Russian Federation.”

US Vice President Joe Biden reaffirmed Washington’s backing for Moldova’s territorial integrity and promised to visit the country “to support political and economic resilience, including its democratic reform agenda and energy security.” “We have agreed to step up our partnership and also to assist in the development of defense capacity,” NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said.

ECONOMICS

Slower growth in the Balkans due to the war

Sources: The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, EBRD

The war in Ukraine is still having an impact on the economies of the Western Balkans, according to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). Economic growth in the region moderated in 2022, but household consumption remained resilient to rapidly rising inflation rates, aided by consistent increases in remittances, credit growth, fiscal support measures, and, in some cases, minimum wage increases and public-sector wage increases, EBRD said. Nonetheless, countries in this region are expected to grow also in 2023, but at a slower pace, as risks remain firmly skewed to the downside. On the plus side, foreign direct investments increased in several areas of the region, according to a study conducted by the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies. In terms of annual growth, FDI activity has increased in Q2 2022. Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia are the only exceptions. The subregion’s upward FDI dynamics were likely aided by a revival of the tourism sector following the relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions, as well as some near-shoring activity.

Stefano Giantin

Journalist based in the Balkans since 2005, he covers Central- and Eastern Europe for a wide range of media outlets, including the Italian national news agency ANSA, and the dailies La Stampa and Il Piccolo.