Although amendable by the new administration, Trump’s decision to designate Ansar Allah, the political movement of Yemen’s Houthis, as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) is going to generate long-term domestic and regional implications difficult to handle.

On 11 January 2021, the American Department of State announced the blacklisting of Ansar Allah (coming into force on 19 January) as an FTO. Three leaders of the armed movement, including the political leader and half-brother of the founder, Abdel Malek Al Houthi, were labelled Specially Designated Foreign Terrorists (SDGT). The list included also Abdul Khaliq Al Houthi, brother of Abdel Malek and Abdul Yahya Al Hakim, a powerful military strategist for the area of Sanaa. These leaders had already been under US sanctions since 2014 (travel ban and asset freeze), as well as under UN arms embargo.

The Department of State introduced exemptions for the UN and the Red Cross, on agricultural and medicine import, as well as to allow humanitarian organisations which operate in the Yemen’s Houthi-held areas, to continue aid delivery. But it is not clear how much licences can mitigate the effects of such designation. The new Secretary of State, Anthony Blinken, promised to “reconsider immediately” the FTO classification and ordered its suspension for one month.

The Houthis have often been responsible for attacks against civilians and non-military targets in Yemen, in Saudi Arabia and the Red Sea waters. However, the “FTO designation issue” brings a number of long-term implications which are likely to disempower conflict resolution efforts, and worsen regional security.

In Yemen, this contributes to marginalise further the more pragmatic and bargaining-oriented component of Ansar Allah (for instance, Sanaa-based officials and former loyalists of Ali Abdullah Saleh), conversely empowering the Houthis’ Saada-based wing which is less inclined to political compromise. At the same time, the internationally-recognised institutions of Yemen are likely to reject political talks with a party designated as terrorist.

For Saudi Arabia, the designation looks like a half victory. Since Riyadh was seeking an exit strategy from the Yemen war, having Ansar Allah labelled by the US as a terrorist movement does not help to build a shared and inclusive negotiating process. Moreover, the Houthis are likely to escalate the launch of missiles and drones against the Saudi territory for retaliation (already intensified during 2020), with an awful outlook for border stability. As a result, Saudi Arabia’s military presence in Yemen is going to last as long as zero-sum policy prevails on pragmatic thinking.

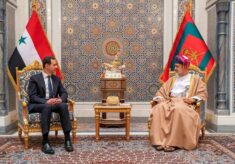

In this scenario, Oman’s traditional foreign policy will likely decrease its manoeuvering, since Muscat used to facilitate Yemeni and regional talks with the Houthis, hosting also informal meetings. Furthermore, the role of Qatar, which played the mediator role between the Houthis and the Yemeni government during the “Saada wars” (2004-2010), could undergo scrutiny as Gulf allies are working to open a renewed cooperative page after the Al-Ula Declaration (January 2021).

Finally, Washington’s choice vis-à-vis Ansar Allah is not a good omen for maritime security in the Red Sea and regional stability: it risks upgrading tensions between pro-Iran forces and American partners. For instance, in January 2021 Israel deployed air defence systems around the port city of Eilat (Iron Dome against UAVs and Patriot missiles to intercept ballistic missile), after the Houthis publicly threatened to attack the city.