[French version: Eau, santé et sécurité mondiale]

The 21st century has outlined a new paradigm of international security, moving from military issues to a new approach based on social, cultural, economic and ecological aspects. In particular, the relation between natural resources and peace and security has been emphasized also by NATO in the 2010 Strategic Concept, enlisting environmental risks as potential stressors for the peace and the stability of the member states of the Alliance.

Without water our lifetime would last no more than 14 days. According to the Third Edition of the United Nations World Water Development Report, published in 2009, by 2030 47% of the global population will experience water scarcity and the calamitous disruptions this can entail. Between 24 and 700 million people will be considered “water displaced”, forced to leave arid and semi-arid areas.

The Coronavirus pandemic reminded us of the link between water access and security and global health.

Many experts have highlighted the catastrophic impact that the lack of access to improved water sources[1] could generate in case of epidemics and pandemics. In 2008, the World Health Organisation released the report Safer Water, Better Health estimating that improving water sanitation and hygiene globally would potentially prevent 9,1% of the diseases and avoid 6,3% of all deaths. In 2014, the Ebola outbreak clearly showed that lack of access to clean water contributed to the spread of the virus.

In 2015 the United Nations General Assembly established, among others, the Sustainable Development Goal 6 which calls for the availability and access to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) for all.

However, the pandemic shed light on the inequalities still existing in our global system. Handwashing is considered a critical aspect to fight COVID-19 but, actually, millions of people do not have water, or, a place where to wash their hands. Only 3 out of 5 individuals worldwide have basic handwashing facilities.

This is urging the international community to renew its efforts to provide investments to improve public health conditions around the world.

Then, we might trace back a connection among countries that do not have access to safe water and those affected by security conflicts.

According to The Water Aid Report’s The Water Gap. The State of the World’s Water 2018 the ten top countries with the lowest access to water are: Eritrea, Papua New Guinea, Uganda, Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia, Angola, Chad, Niger, and Mozambique. All of them ranking in the second half of the 2019 Global Peace Index from low to very low state of peace. Water scarcity is a severe problem and rising tensions could generate more instability and exacerbate regional conflicts. In fragile contexts, in case of epidemics or pandemics, water could be exploited as a real weapon. It could be the root of tensions among states and non-states actors, or being used as a political tool to help states and non-states actors to reach a political goal.

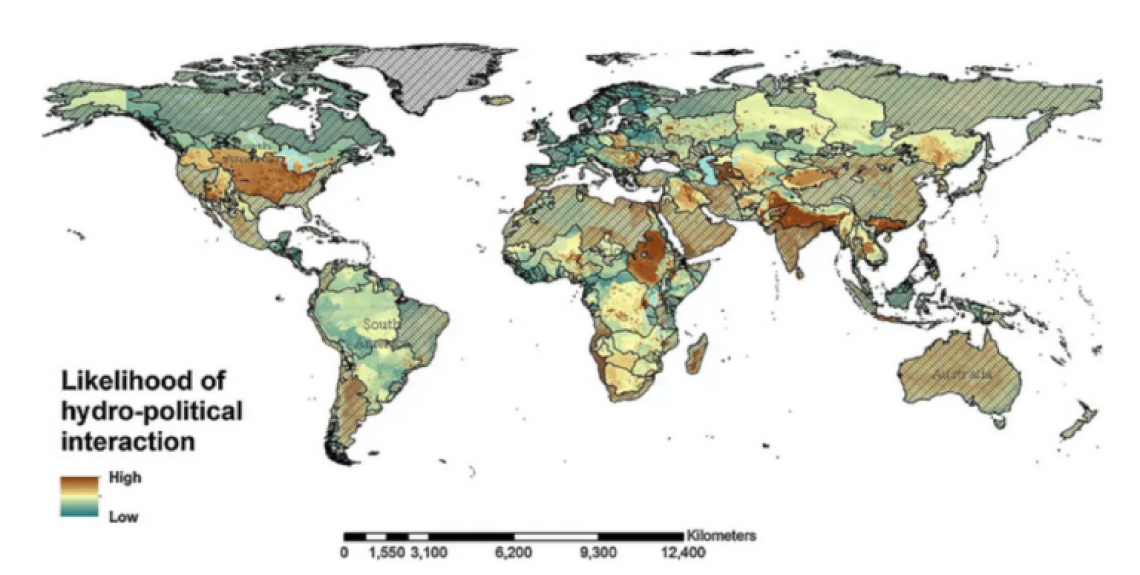

In 2018, the report An innovative approach to the assessment of hydro-political risk: a spatially explicit, data driven indicator of hydro-political issues, edited by a group of scientists of the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission, identified the possible hotspots of water competition between countries, underlying the factors of conflict over water resources: water scarcity, population density, power imbalances and climatic conditions.

Source: Joint Research Centre of the European Commission

The water hotspots where hydro-political interactions are most likely to occur are: the Nile, Ganges-Brahmaputra, Indus, Tigris-Euphrates and Colorado rivers. In additions to these points there are critical situations like: the Amu Darja basin (Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan), Gaza and the Palestinian Territories and Saudi Arabia.

The majority of the countries located around these hotspots are also bottom-performers in the 2015 so-called WaSH Performance Index. The Index compared country performance on increasing access and equity to best performance at different levels of water and sanitation coverage. This finding might become crucial in supporting the nexus between water-global heath-international security. In the next decade, countries could engage in conflicts to protect their access to water and, among other priorities, shore up their internal consensus.

Until now, natural resources have been considered as part of the human rights; however, they took on also a political value that could affect the world security and stability.

[1] Improved drinking water source is a source that, by nature of its construction, adequately protects the water from outside contamination, in particular from faecal matter, see https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/monitoring/jmp2012/key_terms/en/

Federica Lollo

Programme Manager at the NATO Defense College Foundation since 2016. she is specialising in Global Health and the impacts on international security. She is also attending the Mentoring Programme of Women In International Security Italy.